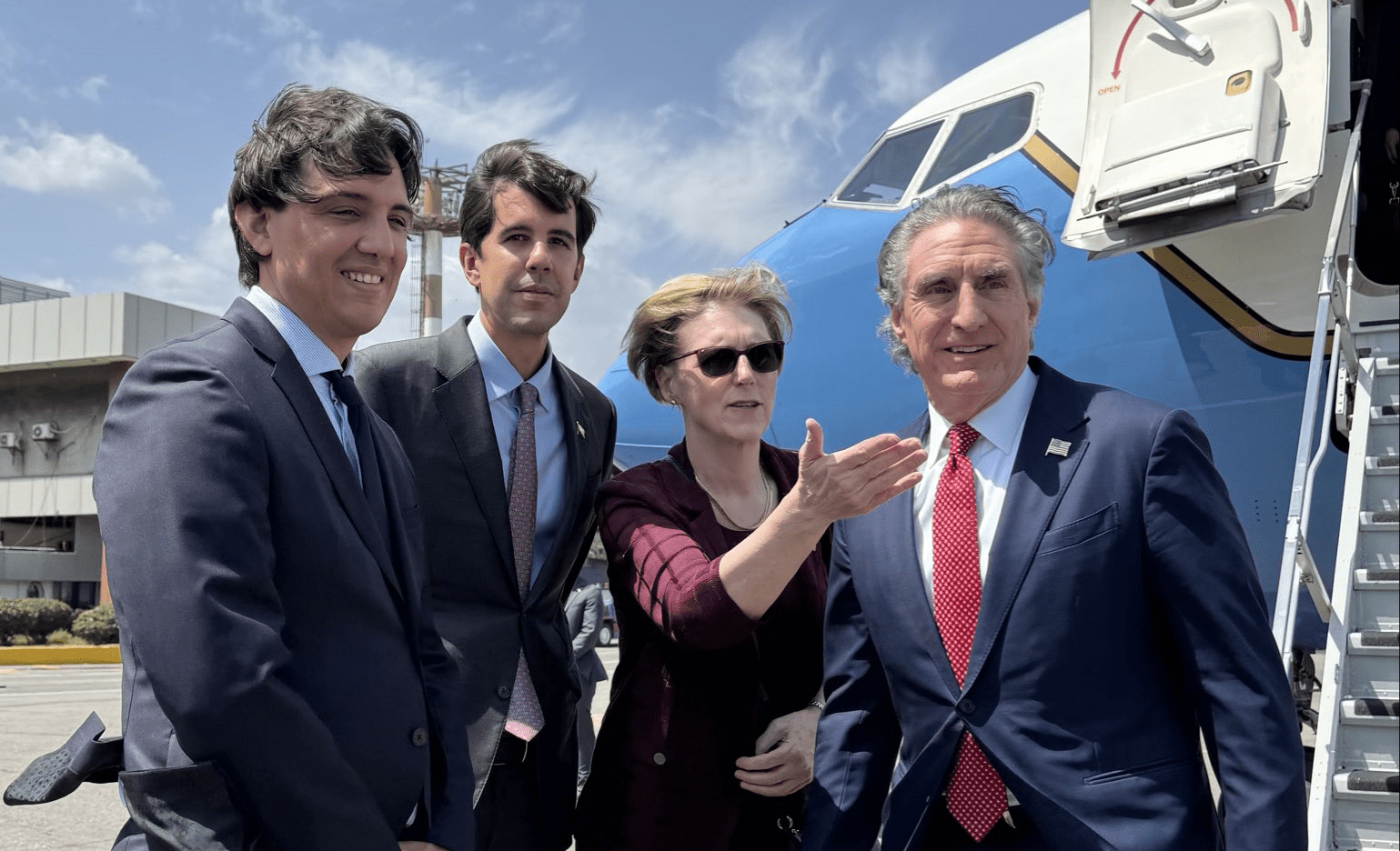

Trinidad and Tobago’s new Prime Minister Stuart Young (right) with Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez in December 2023. Young was then the island nation’s energy minister.

Guacamaya, March 21, 2025. In a move with significant geopolitical and energy implications, Shell has brought forward the production timeline for the Dragon gas field in Venezuelan waters to 2026, aiming to revive the struggling industry of Trinidad and Tobago.

With a submarine pipeline, Washington’s permits under scrutiny, and a new negotiating prime minister, the project faces a complex landscape of risks and opportunities that could redefine the Caribbean’s energy map.

The Dragon field, with reserves of 4 trillion cubic feet of gas, will connect to Trinidad via a 16 km pipeline to supply the Atlantic LNG plant, which is currently operating at half capacity. The goal is to extract the first gas by 2026, a year ahead of schedule, according to Reuters, which received information from sources close to the project.

The island, which saw its LNG production drop to 8.5 million tons in 2023 (compared to a projected 12.5 million), is betting everything on Venezuelan gas. The objective is clear: to prevent the collapse of Atlantic LNG, where British Petroleum has already dismantled an inactive train, and to reposition itself as a strategic exporter. Trinidad has warned that access to gas in the joint project with Venezuela is crucial for the “energy security of the Caribbean.”

The Washington Factor: Sanctions and OFAC

Although the U.S. authorized the project until October 2025, the shadow of sanctions looms. In March 2025, Washington revoked Chevron’s permit in Venezuela, signaling potential policy adjustments.

Shell’s and the state-owned NGC’s licenses to operate in the Dragon field and the binational Manakin-Cocuina field (1 trillion cubic feet) expire in 2025 and 2026, respectively, leaving the island’s government with significant uncertainty. Recently, Trinidad alerted the White House that blocking the project would cost it access to 5 trillion cubic feet of gas, equivalent to a decade’s worth of supply.

It is important to recall that in the Memorandum of Understanding signed by the United States and Venezuela on March 28, 2023, during the Doha negotiations mediated by Qatar, Phase 1, point number 3 of the actions Washington would undertake includes “modifying the license for Trinidad and Tobago to allow cash payments and transactions associated with the Bank of Venezuela.” This specific point is what enables the reactivation of the Dragon field.

The license stemming from this agreement has broad geopolitical implications, which is why the government of Trinidad and Tobago is pushing for its continuation despite the political tensions between Caracas and Washington.

Stuart Young: The Architect of the Alliance with Venezuela Now Becomes Prime Minister

Young studied law at the University of Nottingham (United Kingdom), was admitted to the Bar of England and Wales in 1997, and obtained a certificate from the Hugh Wooding Law School in Trinidad in 1998. All of this led him to politics, and before leading the cabinet, he held key positions: Minister of Energy and Energy Industries and Minister in the Office of the Prime Minister.

The new Trinidadian prime minister, in office since March 2025, brings with him a broad agenda from his experience as Energy Minister.

During his tenure, he successfully negotiated gas prices with Venezuela without subsidies and secured full export to Trinidad, with no domestic consumption for PDVSA. He forged an important alliance with Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez to unblock projects stalled for a decade. Additionally, he negotiated key licenses with the U.S., though their renewal will depend on political volatility.

Despite the tense situation between the United States and Venezuela, Young’s circumstantial rise to power in Trinidad and Tobago will grant him the authority to negotiate as the highest authority with Washington to maintain the project. He faces significant challenges and resistance within the Trump administration due to the implications of the sanctions on Venezuela. However, having been the architect of the current agreement, his room for maneuver increases significantly, as he will no longer negotiate as a minister of a government but as the head of a cabinet that he leads.

Regional Impact: The Dragon Project: A Key Piece in Global Energy Geopolitics

The Dragon project is not just about gas; it is an experiment in cooperation amid sanctions. If successful, it would set a precedent for energy integration in Latin America. If it fails, it would expose the limits of diplomacy in the face of U.S. geopolitics.

Meanwhile, Shell is drilling against the clock, Trinidad is sharpening its export ambitions, and Venezuela is looking toward the Caribbean, seeking relief from its economic siege. The board is set; the dice are rolling.

The gas from the Dragon field could lower local costs and prevent social crises, which is critical for the United States as it seeks to avoid mass migrations and instability near its borders. For Europe, access to this gas could reduce costs in a context where Brussels is looking to rearm and needs to prioritize investments in the defense sector.

Maintaining the project could be in the interest of the United States, as Trinidad could become a key partner in containing Chinese and Russian influence in the Caribbean. In the past, the company Rosneft was interested in operating in this project, but it ultimately did not materialize.

For its part, China’s presence in the Caribbean is something that worries the United States, especially the Trump administration, which sought to focus its efforts on the Asia-Pacific. An important fact is that of the twelve countries that still recognize Taiwan as the Republic of China, seven are in Latin America and the Caribbean (Guatemala, Belize, Haiti, Paraguay, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Saint Lucia). The People’s Republic of China’s interest in increasing its influence in the region is to weaken Taiwan’s diplomatic position before 2040, a key objective of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, therefore each space and project in the region takes on significant relevance.

The situation in the Middle East between the United States and Iran appears to be growing increasingly tense, particularly in Yemen, where a Houthi escalation could boost demand for Caribbean LNG. However, it could also raise the cost of inputs needed to develop the Dragon field (equipment imported from Asia or Europe).

Trinidad and Tobago aims to partially compete with Algeria or Qatar as an LNG supplier for niche markets, leveraging its geographic proximity to the United States and the geopolitical situation with Europe, where tensions in the Red Sea could disrupt supply. Unlike the nations of the Middle East, which remain embroiled in conflict and uncertainty, Trinidad is located in a region free from such turmoil.

On the other hand, if the conflict in Ukraine persists, the EU—and particularly Germany, which has shown interest in acquiring gas produced from the Dragon project—could pressure the United States to maintain projects like Dragon, even relaxing sanctions due to their energy needs. However, this faces significant obstacles due to the deterioration in relations between the European Union and the United States since Trump took office.

The Dragon field project is not just a gas venture: it is a piece on the chessboard of 21st-century geopolitics. Its success will depend on Trinidad and Shell navigating sanctions against Venezuela, the war in Ukraine, and attacks in the Red Sea. For Washington, it could be a “necessary evil”; for Europe, “a hope”; and for the Caribbean, a respite from the geopolitical storm.