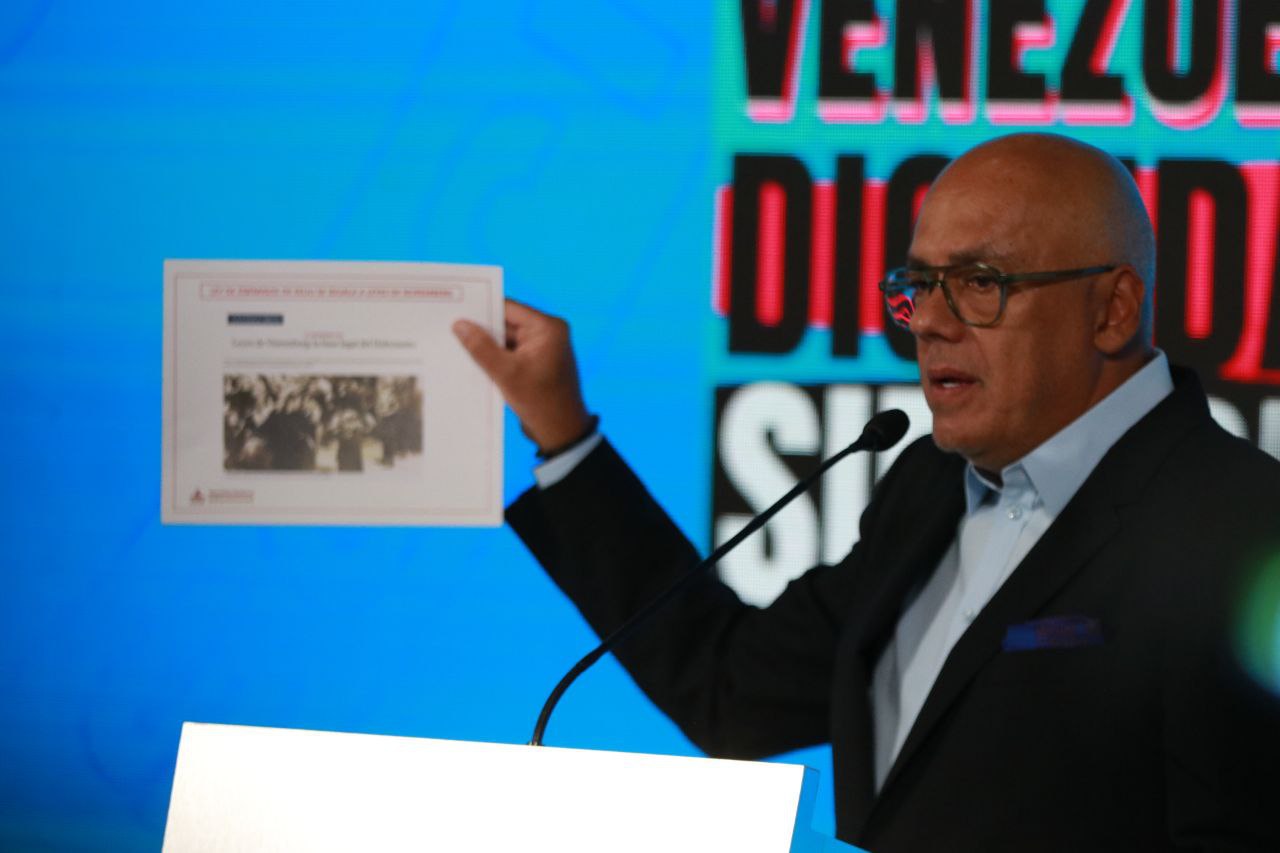

Jorge Rodríguez, the president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, is also Caracas’ chief negotiator with the U.S. government. Photo: National Assembly.

Guacamaya, March 17, 2025. Jorge Rodríguez, the Venezuelan government’s chief negotiator with the United States, denounced on Monday the deportation of 238 Venezuelans to a “mega-prison” in El Salvador, as well as the use of the 1798 “Alien Enemies Act” against his co-nationals.

Rodríguez described the act as a “crime against humanity” and promised to exhaust all legal, diplomatic, and political avenues to repatriate the affected individuals to Venezuela, while urging his compatriots to avoid traveling to the U.S.

The National Assembly president, who is also the main government negotiator with Washington, did not hold back during a press conference in Caracas: “In the United States, there is no rule of law for our migrants. We will use all mechanisms, even talking to the devil, to bring them back!” he declared. He also proposed that the Venezuelan government issue a formal travel warning to discourage trips to the U.S., accusing the country of “criminalizing migration.”

The spark of the conflict was the mass deportation of Venezuelans linked by Washington to criminal activities. The White House claimed that those deported are members of the Tren de Aragua, though without presenting evidence. They were expelled and sent to a third country under a 1798 wartime law reactivated by the Trump administration. According to Rodríguez, this action “violates international law” and will be denounced by Venezuela in global courts.

Rodríguez stated that Venezuela will make “all available planes ready to search for Venezuelans who wish to return to the country.”

U.S. Position

The White House defended the deportations, arguing that those transferred are “terrorist foreigners” and that the court order blocking the measure, issued on Saturday by Judge James Boasberg, is invalid. Presidential spokesperson Karoline Leavitt insisted on X: “The Supreme Court supports the president’s authority in national security matters.”

However, the application of the “Alien Enemies Act,” designed for times of declared war, has raised skepticism. Legal experts emphasize that the U.S. is not in a state of war with Venezuela, questioning the legal basis for the measure.

When asked about the deportations, the U.S. State Department referred to a statement by Secretary Marco Rubio, which labeled the Tren de Aragua as a “foreign terrorist organization.” It also thanked Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele for offering to imprison “these violent criminals,” referring to the deported Venezuelans.

The department declined to answer further questions, including whether it can be confirmed that the deportees are members of the Tren de Aragua, whether Venezuelans are being deported to other countries, or how much the U.S. is paying El Salvador to receive and imprison migrants. According to AP, the Trump administration will pay $6 million.

Reactions Within Venezuela

Provea, a human rights organization, denounced that the deportees face a “legal limbo” in El Salvador, without access to lawyers or family members.

On the other hand, opposition leaders such as Ramón Guillermo Aveledo and Andrés Caleca condemned the deportations and the “cruel” treatment of Venezuelans.

In a statement, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs compared the deportations to “Nazi concentration camps” and blamed U.S. and European Union economic sanctions for the migration crisis. It also targeted opposition figures such as Leopoldo López, Carlos Paparoni, and María Corina Machado, linking them to human trafficking networks and “measures that stigmatize the people.”

The situation arises just days after the U.S. decided to revoke Chevron’s license, requiring the oil company to cease operations in Venezuela.

Historical Background: A Law in the Eye of the Storm

The “Alien Enemies Act,” created in 1798 during tensions with France in what was known as the “Quasi-War,” allows the U.S. president to expel citizens of “enemy” countries during wartime. Its use in 2025 marks the first application in 80 years, reviving debates about racism and national security in U.S. immigration policy.

Unlike other similar laws that have expired or been repealed, this one remains in effect today, though it has only been activated in specific conflicts.

The law authorizes the U.S. president to detain, deport, or restrict the activities of male citizens over 14 years old from a country considered an “enemy” during a “declared war” or an “armed invasion.”

During World War II, it was used to justify the detention of over 10,000 Japanese, German, and Italian citizens. The mass internment of Japanese-Americans was based on another regulation known as “Executive Order 9066.”

During the Cold War’s “Second Red Scare,” fueled by McCarthyism, the law was used to support measures against foreigners accused of sympathizing with communism or spying for Warsaw Pact countries.

What’s Next?

Venezuela has stated that it will present the case to the International Criminal Court and the UN, among other organizations. The Venezuelan government has also launched a digital platform for the families of Venezuelan migrants to report if they are in such a situation.

Diosdado Cabello, vice president of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela and Minister of the Interior, has reiterated calls for a march in “solidarity with migrants” and warned that “U.S. satellite governments in the region could take similar actions against Venezuelan migrants.” He also questioned the silence of international organizations like the UN regarding the situation.

Notably, in his statements and criticisms of the U.S., Jorge Rodríguez did not directly mention or blame Trump or his special envoy for Venezuela and North Korea, Richard Grenell. The latter has been the main liaison between Caracas and Washington since his visit to Venezuela on January 31. The Venezuelan government’s statements have directed their criticisms at Secretary of State Marco Rubio and opposition figures.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration could face legal pressures if it is proven that it circumvented Saturday’s court order. The 238 deportees remain in El Salvador’s mega-prison, a penitentiary experiment by President Nayib Bukele that has faced international and human rights organizations’ scrutiny.