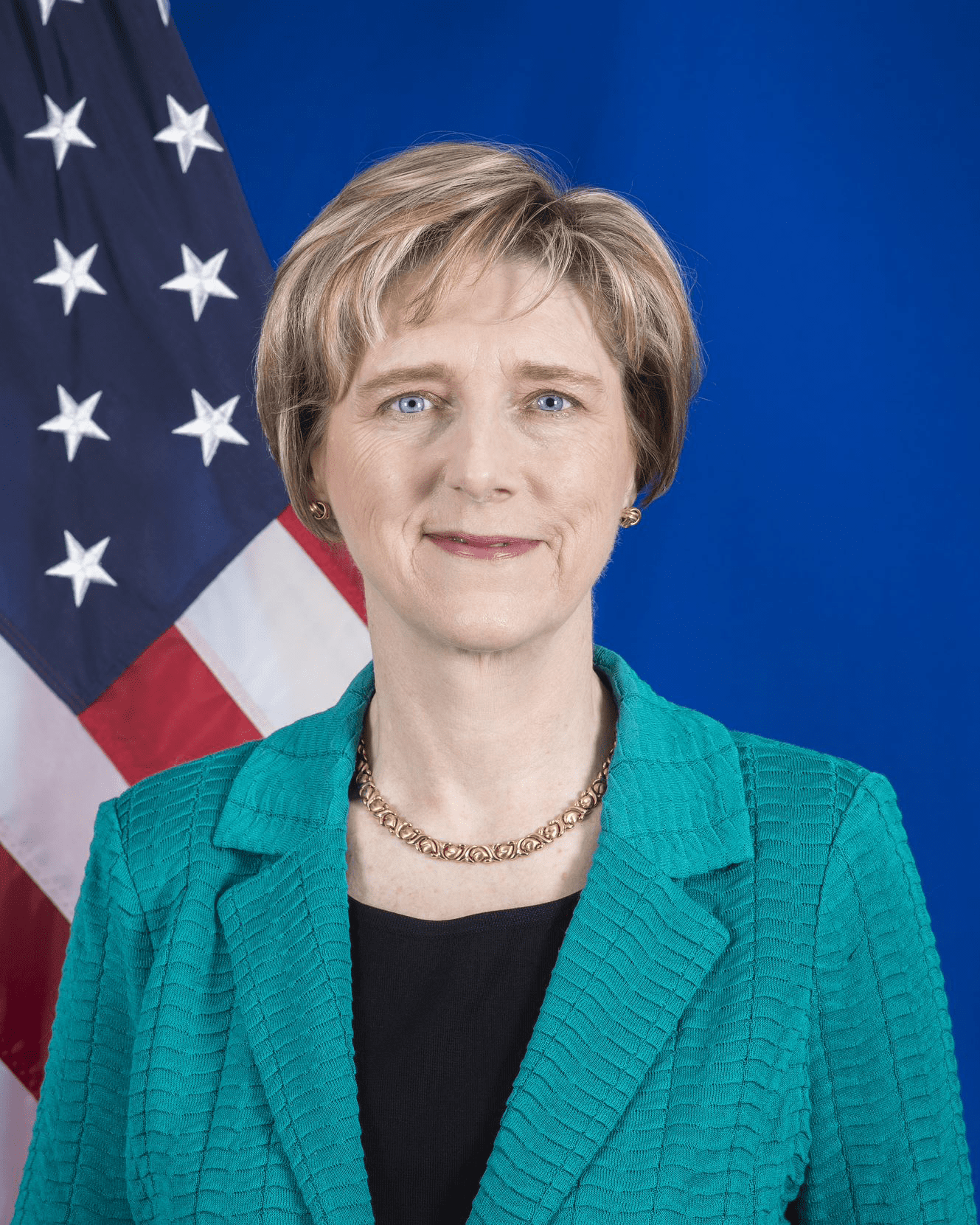

Representing Venezuela were Yvan Gil, the government’s Foreign Minister, and Gabriela Jiménez, Minister of Science and Technology. Photo: social media.

Guacamaya, August 25, 2025. The fifth presidential meeting of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) concluded with a joint declaration that, while reaffirming the eight member countries’ willingness to defend the rainforest, highlighted the deep divisions regarding the future of hydrocarbons in the region.

The host, Gustavo Petro, celebrated some consensus points: the creation of a fund for tropical forests, the establishment of an indigenous co-governance mechanism within ACTO, and the installation of an international police intelligence center in Manaus, Brazil. To these is added the bloc’s next meeting, scheduled for 2027 in Ecuador.

However, the so-called “Bogotá Declaration” sidestepped the strongest demand from indigenous communities, scientists, and civil organizations: to prohibit oil exploitation in the Amazon. The proposal, initially championed by Petro, foundered due to explicit resistance from Venezuela, Ecuador, and Peru, and the ambiguity of Brazil, whose president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva insisted that oil is a necessary resource to finance his country’s energy transition.

The final document merely promised a path toward a “just, orderly, and equitable transition,” qualified by the “national circumstances” of each state. The international coalition Amazon Free of Fossil Fuels lamented the setback, accusing governments of sacrificing environmental urgency for extractive interests.

Regarding security, Lula announced that a center for Amazonian police cooperation will be inaugurated in Manaus in September, in coordination with the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the Andean Community. The creation of a regional security commission and a gold traceability proposal to combat illegal mining were also ratified.

One of the most concrete outcomes was the formal inclusion of indigenous peoples in ACTO’s governance, with one indigenous delegate and one governmental delegate per country. “We hope its first session will be as soon as possible,” stated Ginny Catherine Alba of the National Organization of the Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon (OPIAC). Even so, Afro-descendant leaders noted that they remain excluded from these decision-making spaces.

How was Venezuela’s participation?

On the political front, Venezuela used the summit to denounce U.S. sanctions and demand respect for its sovereignty. Foreign Minister Yván Gil emphasized that the common declaration included a rejection of “unilateral coercive measures.” In this regard, Gabriela Jiménez, Minister of Science and Technology, stressed that Venezuela is among the ten countries with the largest wetland areas in the world, reinforcing the importance of its role in protecting the Amazon biome. She insisted that decisions about this territory must come from the Amazonian peoples themselves and their governments, through dialogue, knowledge, and cooperation, without external impositions.

She also highlighted that the Amazon’s biodiversity holds strategic value not only for its water and mineral wealth but also as a vital reserve for future generations. Among the action plans, she mentioned using satellite imagery to monitor forest behavior and photosynthesis processes, tools that could form the basis for reforestation and ecological recovery programs for the rainforest.

However, organizations like PROVEA criticized the Venezuelan delegation for using the forum more as a propaganda platform than for a real commitment to the socio-environmental crisis affecting its own Amazonian territory. The Venezuelan government has rejected these accusations for years.

In Venezuela’s case, the Amazon holds strategic relevance: the country contains between 5.6% and 6.1% of the entire Amazon rainforest, representing approximately 470,000 km² distributed mainly in the states of Bolívar, Amazonas, and Delta Amacuro. This vast territory hosts unique biodiversity, vast reserves of freshwater and strategic minerals, as well as indigenous communities that depend directly on the forest for their survival. Therefore, Venezuelan environmental policy is crucial within ACTO, though it is often criticized due to tensions between resource exploitation, military presence, and socio-environmental protection demands.

Finally, all countries backed the Brazilian proposal to present a Tropical Forest Forever Fund (TFFF) at the COP30 in Belém, which will seek to economically reward the preservation of hectares of rainforest, going beyond traditional carbon credit mechanisms. “It will be the COP of truth,” Lula warned.

Amid partial consensus and open disputes, the Amazon remains at the center of a crossroads: to preserve the planet’s largest lung or to maintain its exploitation as a source of income amidst national economic crises.