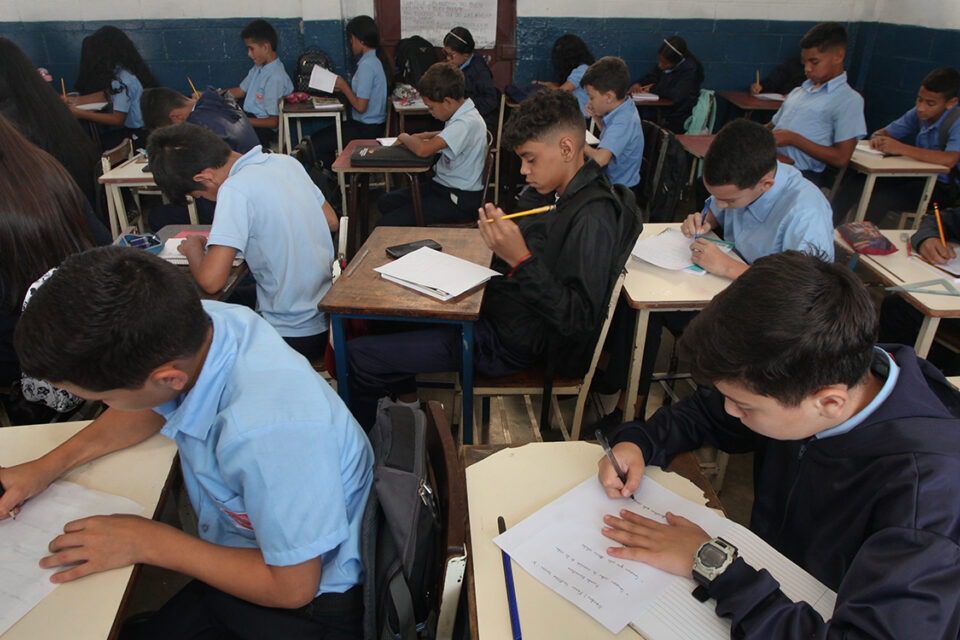

The Venezuelan education system, at the beginning of the Christmas recess, shows an opacity and lack of responses to a complex context that threatens the continuity and quality of the right to education in the country. Photo: GlobalStock | iStock.

Guacamaya, December 14, 2025. This Friday, December 12, the first pedagogical moment of the 2025-2026 school year in Venezuela culminated and thus began the Christmas vacations that will last for a month, until January 12, 2026. This break comes in a context in which expectations and concerns are still expressed about the progress and challenges that marked the beginning of the school year.

A month ago, on November 6, in a virtual meeting with state directors, the Minister of Education, Héctor Rodríguez, reported progress in the review of this first academic period. Although on that occasion he highlighted the progress in various and important aspects, publicly no details were expanded on the matter, which has left the door open to many doubts.

Among the improvements mentioned, progress in student enrollment, school time, educational programs, the logistics of the School Feeding Program (PAE), educational infrastructure and management processes in schools was highlighted. As updated figures and data are not specified, it is unknown if the aforementioned advances have met the goals set at the beginning of the school year.

Despite keeping registration open during the period, the Venezuelan government barely met a limited portion of its goal of reinstatements in student enrollment. With a record of 110 thousand refunds out of 500 thousand set before the start of the school year, and without updated figures, it is far from reversing the exclusion of 3.9 million reported by Encovi 2024.

One of the few advances has been made in the regulation of homework. Days ago, Minister Rodríguez announced the implementation of this proposal, whose discussion began in October with the installation of an evaluation commission. The application of the regulations, still unknown, seeks to “prioritize the quality of learning and guarantee the right to free time.”

After the planning and integration that characterize this first period, the academic calendar still has two periods left, focused, respectively, on educational transformation and the closure of learning projects. These will serve both to evaluate the proposed regulation, if it is applied, as well as other aspects that put the continuity and quality of the right to education in the country under the magnifying glass.

Children and Young People Outside the School System

One of the most critical problems in recent years is the high number of children and young people outside the education system. The latest National Survey of Living Conditions (Encovi), corresponding to the year 2024, reflected that approximately 3.9 million Venezuelans of school age are not enrolled or attend classrooms. This is equivalent to a schooling rate that barely exceeds 70%.

Indirectly, the Ministry of Education recognized this situation and since the end of the previous school year began a deployment to reincorporate these people. For the 2025-2026 school year, the national government, in the voice of President Nicolás Maduro himself, set a goal of 100% schooling and proposed the incorporation of more than 500 thousand students, according to the Vice Ministry of Facilities and Logistics.

However, Minister Rodríguez himself reported the incorporation of 110,000 students at the start of classes in 2025, a far cry from the population excluded according to Encovi 2024, and from the goal set by the Government itself. Although Maduro ratified the goal of 100% schooling by 2025-2026 and the Ministry announced progress in this area, after the first period, current figures on enrollment are unknown.

The exclusion of school-age people is linked to structural poverty that limits access due to lack of basic resources. For this reason, the Government emphasized allowing registration, despite the conditions. “If the child does not have shoes, does not have a uniform, does not have the tools, we give it to them, but we cannot leave any child unenrolled,” Rodríguez said at the time.

School Conditions: the PAE and infrastructure

In line with the above, food is still an essential issue in the integrity and continuation of school activities. In this way, the School Feeding Program (PAE) represents one of the most relevant social policies within the educational system, aimed at guaranteeing the basic nutrition of students to improve their performance and permanence.

On the one hand, during the 2024-2025 school year, the Government reported a 36% increase in the distribution of food in schools, in addition to highlighting a better nutritional quality with more proteins, fruits, and vegetables. Although in November the Ministry of Education reported further progress in the logistics of the PAE, the real scope of this announcement is still unknown.

In contrast, social organizations have pointed out that the distribution of the PAE is irregular in many regions and that it does not always reach all schools. The situation, of course, affects the attendance and concentration of students, key elements for their permanence. “One of the things that the government should do is guarantee continuity,” says Fenasopadres in this regard.

In relation to infrastructure, the lack of sustained investment has generated a progressive deterioration. Last July, the number of about 900 schools intervened with rehabilitations was reported, but there are still centers with serious damage and many repairs are insufficient. In addition, communities must take responsibility for supervision to ensure that the work lasts.

To address these aspects, the Venezuelan education system requires a multimillion-dollar investment. At a conference in April, professors and experts Luisa Pernalete, Carlos Calatrava and Jaime Manzo estimated that incorporating 3 million children and young people out of the system implies building around 18,461 new educational institutions and training about 195,000 new educators with decent salaries.

For this to be implemented, investments between $6,000 and $13,000 million a year are needed, according to experts. This goal is a challenge for the state and for all civil society that requires public-private partnerships, international cooperation and stable comprehensive plans. The objective is to adapt the educational system to the needs of the school and teaching population and thus encourage permanence.

School Performance and the Profile of the Venezuelan Student

Another of the essential indicators of quality education is school performance and this has been a task to be carried out in recent years. The latest report from the Online Knowledge Assessment System (SECEL) of the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB), reflects this. Levels of knowledge in key areas such as mathematics and communication experience a progressive deterioration.

The report, which studied the academic performance of Venezuelan students in the 2023-2024 period, recorded overall averages that barely exceed 7.5 points out of 20 in the aforementioned areas. The research, aimed at the evaluation of students from sixth grade of primary school to fifth year of high school, showed a negative trend during the last five years.

In turn, the SECEL-UCAB study evidenced, albeit slightly, a growing gap between public and private schools. Of course, the latter maintain better educational standards due to better resources and conditions, while public schools face desertion, lack of qualified teachers and infrastructure limitations.

This issue is even more alarming if one takes into account that private schools barely cover 12% of the country’s school population, according to the National Federation of Associations of Parents and Representatives (Fenasopadres). This indicates that more than 85% of student demand must be satisfied by the State. This inequality limits development opportunities for millions of students.

On the other hand, with mass migration, a phenomenon related to the particularity of the educational profile of the Venezuelan exodus is generated. The situation, in addition to generating an inevitable reduction in students in the country, also favors a segmentation in the academic profile of Venezuelans abroad, which affects the relay training and national educational expectations.

According to a 2021 report by Colombia’s National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), a large portion of Venezuelan migrants have low or non-existent levels of formal education. However, there is a significant presence in technical and higher education in certain groups, indicating that the new migrant generations are associated with a higher dropout rate.

The Crisis of Teachers and Limitation of Teaching Practice

Undoubtedly, a critical fact within the already complex situation that the Venezuelan education system is going through is the deficit of teachers. The Venezuelan Program for Education-Action in Human Rights (Provea) reported last September a 70% decrease in teacher training between 2008 and 2022, with an even more pronounced drop of 80% in the graduation rate.

Specifically, in 2022 there were only 2,000 graduates in teacher training, compared to the figure of more than 17,000 graduates reached in 2008. The trend suggests that by 2030, there will be no graduate professors in the country. In this context, the NGO Monitor DascaVE warned of the need for some 250,000 teachers to cover the existing deficit.

A phenomenon that has been generated from this reality is the so-called “aging” of the teaching staff and an almost total lack of replacement generation, especially in scientific and mathematical areas. “In the last class of the Pedagogical Institute of Caracas, for example, only one mathematics teacher graduated,” Tulio Ramírez, director of the Doctorate in Education at UCAB, told Provea.

In contrast, the Ministry of Education celebrated an increase in interest in studying Education, with greater enrollment in pedagogical institutes. Thus, a new academic period was reported with 56,000 students in the training careers that serve the entire basic education subsystem, 193,176 educators in training courses and another 28,232 who are undergraduates.

Although the government officially denies the deficit, precarious working conditions continue to drive migration and teacher desertion. In addition to the leakage, many practicing teachers also face functional limitations, especially in schedules and resources. The official measures that force full schedules to be complied with without guaranteeing improvements still generate doubts and resistance.

After the pandemic and since 2022, it has been common in many schools to use the so-called “mosaic schedule”, a modality of reduction in class hours that responds to the precariousness of teachers’ salaries and logistical difficulties. In 2025 the government decided to eliminate this scheme, and although improvements in school time were announced last November, the absence of data does not allow us to know its scope.

In this regard, many teachers believe that without better salaries and minimum working conditions, it will simply not be feasible to maintain attendance or pedagogical quality. The situation reflects the tension between official policies and realities in the classroom. Conflicts and doubts around these aspects continue to accentuate the deterioration of the teaching work.

Situation of University Education

No educational stage escapes reality and when talking about academic quality, the university level cannot be left aside. In this sector, teachers’ salaries also do not cover basic needs and precarious working conditions also encourage migration. According to the Observatory of Universities (OBU), Venezuelan university professors are the poorest on the continent.

At the higher level, university autonomy also faces political and financial tensions that limit its functioning. This year, the National Council of Universities (CNU) decided to eliminate internal admission tests in public universities. The measure strips institutions not only of a modality that favors excellence but also of a source of financing.

Although these types of measures and consequences are not exclusively an academic problem, they do affect advanced training and research, which are essential to mitigate the educational crisis with new leadership and knowledge. Of course, the pressure on autonomous university institutions also limits their own capacity to respond to the system in crisis.