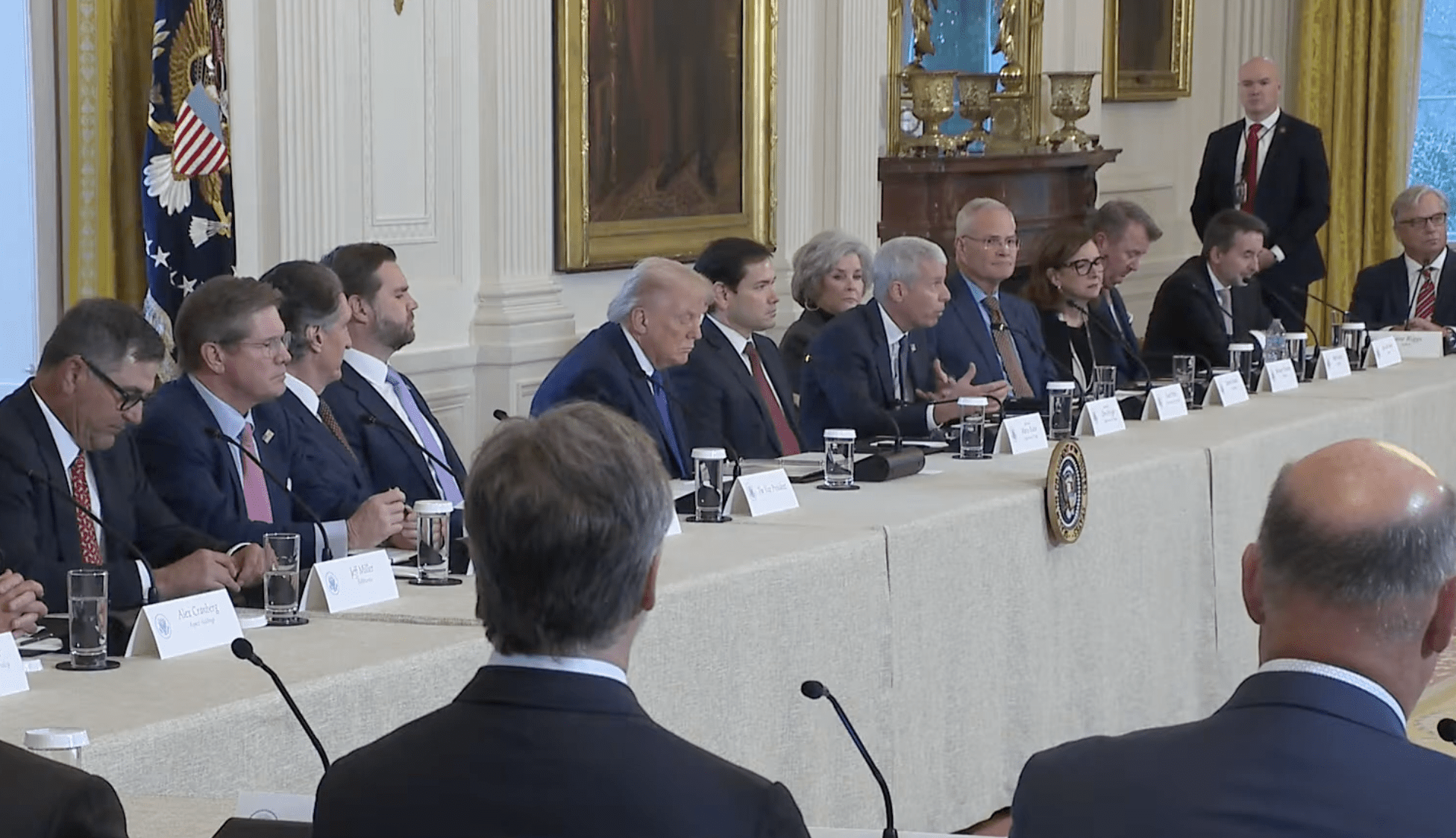

Sergio Vieira de Mello, when he was Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Iraq in 2003. Photo: UN / Mark Green.

Guacamaya, June 6, 2025. Amid refugee camps, in the rubble of a failed state, or in the gray halls of international diplomacy, there was a man who believed in the impossible: rebuilding peace from human dignity. His name was Sérgio Vieira de Mello, a Brazilian diplomat, a philosopher by training, and one of the most human and tragic faces in the recent history of the United Nations.

There was something about Sérgio Vieira de Mello that defied all molds. He had the composure of an academic and the courage of a firefighter. Philosophy in his mind, but dust on his shoes. He was not an office diplomat: he was a man who chose to inhabit chaos, to live literally on the front lines. He negotiated with militiamen, authoritarian leaders, refugees, and bureaucrats with the same mix of patience, irony, and an almost brutal clarity of purpose.

His story is not just a biography; it is an uncomfortable mirror of what it means to build peace when the world is in ruins. A tale where ethics, heroism, and power do not always walk together, and where the moral cost of peace can be as high as that of war.

A Peacebuilder Amid Wars

Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1948 and educated at the Sorbonne, he joined the UN in 1969 as a volunteer for UNHCR. In his early years, he witnessed refugee crises in Bangladesh, Cyprus, and Sudan. But his mettle was truly forged in Rwanda, Cambodia, East Timor, and the Balkans.

In Rwanda, he saw humanity at its worst. He arrived too late, like almost everyone. He saw stacked bodies and shattered communities. There, he witnessed the horror of genocide and international inaction. Stacked bodies. Broken communities. How does one maintain morality when negotiating with those who caused so much harm?

For Sérgio, that was the wrong question. “You have to talk to the armed men,” he said. He did not seek purity; he sought results. “You don’t negotiate with angels in the middle of a civil war.” As Samantha Power (2008) noted, “He did not believe in the sanctity of good intentions, but in the efficacy of hard decisions.”

East Timor and the Politics of the Possible: Sérgio the “Nation-Builder”

After the genocide in Rwanda and the failure in Bosnia, he arrived in East Timor. In 1999, the UN tasked him with an unprecedented mission: to build a state from scratch. Leading the United Nations Transitional Administration (UNTAET), he applied an unorthodox approach: instead of imposing, he listened. Instead of punishing, he reintegrated.

He spent afternoons with local leaders, victims, and even former executioners. He preferred that to press conferences or interviews. His premise was simple: “You cannot impose democracy like you impose a constitution.”

Timor was not perfect. There were mistakes, delays, and contradictions. But there was also a partial miracle: a small, devastated country managed to rise. And much of that credit went to this Brazilian with a tense smile and a wrinkled suit.

“Lasting peace is only possible when built with the real actors of the conflict,” Power (2008) recalled when writing about Sérgio. His work was a choreography between international legality, local reality, and the scars of violence.

Cambodia and the Ghosts of Angkor

In Cambodia, the temples of Angkor Wat emerge from the jungle like sacred ruins, silent witnesses of a civilization that flourished and fell. But in the 1990s, the real ghosts were not in the ancient stone but in the ravaged villages, the buried mines, and the empty gazes of those who survived the hell of the 20th century.

In Cambodia, memory is a minefield. Not just because of undetonated bombs, but because of words that still hurt, names that still instill fear. In the early 1990s, the Khmer Rouge were still active. They were no longer the rulers of the country, but neither were they defeated. And in that limbo of impunity and residual power, peace was merely a fragile promise.

Sérgio Vieira de Mello arrived in this transitioning country as part of one of the most ambitious UN missions deployed up to that point, the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). The challenge was enormous. Not only did they have to organize elections, repatriate hundreds of thousands of refugees, and disarm combatants, but they also had to rebuild trust in a country where neighbors had learned to distrust even the living.

Sérgio, with his trademark mix of diplomacy and skepticism, understood that in Cambodia, it was not just about applying international protocols. One had to listen. One had to read the silences. In his reports, he insisted that human rights could not be defended from a desk. One had to walk the fields, sit with the victims, understand trauma as a political condition.

Sérgio was marked by the contrast between the UN’s ambition and Cambodian reality. The international bureaucracy spoke of democracy, but in the villages, the most repeated word was silence. Silence about the past. Silence about the disappeared. Silence about justice.

As in Timor later, in Cambodia, he understood that peace is not an event. It is a process. And that process is not decreed: it is cultivated, with patience, with respect, and above all, with real presence.

From his time in Cambodia, Sérgio took away a hard but necessary lesson: reconstruction does not begin at the ballot box or in press conferences, but on the ground. He learned that denouncing human rights violations is not enough; they must be prevented. And to prevent them, one must be there, listen, mediate, talk to everyone, and accompany.

Cambodia was not his most famous mission. But it was perhaps one of the most formative. There, he saw how a country could be lost even after winning peace. There, he reaffirmed that his place was not in the capitals of the global North, but where the world unravels and must be rewoven.

Sérgio Vieira de Mello played a significant role in negotiations with the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, being the first UN representative to make contact with them. His work in Cambodia, through UNHCR, focused on the repatriation and reintegration of refugees, and he was also the UN Special Envoy for Cambodia. He was the first to build a bridge with the Khmer Rouge despite the criticism and political cost of negotiating with such a group.

Sérgio Vieira de Mello’s approach to the Khmer Rouge was one of those diplomatic decisions that, from the outside, may seem controversial, but from the ground, were deeply necessary.

Proximity Diplomacy

The approaches were not public or grandiose. Nor were they formal recognitions. They were conversations on the margins, assessments of conditions, signals of openness. Enough to create channels of contact. Enough to prevent a new offensive. Enough to ensure that silence would not be filled with gunfire and victims.

That kind of diplomacy—silent, often misunderstood, and questioned—was what Sérgio mastered. He did not make speeches for the press, awards, or applause; he made gestures for peace.

Vieira de Mello, far from justifying crimes, understood that ignoring the existence of the Khmer Rouge would only prolong the conflict. Therefore, as part of the UN’s strategy to consolidate peace, he favored indirect dialogue with their leaders, opening communication channels that would allow their eventual demobilization and reintegration. All this under an approach centered on the victims, not on moral purity.

For Sérgio, the priority was civilians, not political correctness. He knew that refusing to talk to the Khmer Rouge could condemn thousands of Cambodians to more violence, and so he defended what he called “proximity diplomacy”—the kind that involved talking even with the darkest actors if it could save lives.

Vieira de Mello was not naive. He did not believe the Khmer Rouge would become democrats, but he did believe they could be contained if offered a political exit that facilitated disarmament and transition. He understood that justice had to be built on stability, not the other way around. The urgent task was to stop the cycle of war.

Was talking to the Khmer Rouge an ethical surrender? A pact with evil? Vieira de Mello would have responded with another question: How many lives are you willing to lose to maintain a perfect stance?

Today, many remember Sérgio as the man who was not afraid to look horror in the eye if it could bring him closer to peace. Not to forgive. Not to forget. But to stop the harm.

Bosnia: The Price of Facing Reality

Bosnia was a shattered mirror of Europe. A land where the promises of “never again” crashed against the reality of ethnic cleansing and mass graves. There, in the heart of the “civilized continent,” a war erupted that exposed the impotence of the international community.

And there, too, was Sérgio Vieira de Mello. Not with tanks or escorts, but with his field notebook and a radical sense of human responsibility. Bosnia was an open wound that marked his worldview. A place where commitment to peace was not a slogan, but a gamble with too many enemies.

Vieira de Mello arrived in Bosnia as part of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). His mission: to coordinate humanitarian aid. But in a country where front lines moved to the rhythm of hatred, delivering food or medicine was a political act.

What he saw in Bosnia transformed him. Devastated villages. Civilians as weapons of war. Children with eyes empty of hope. And above all, an international community paralyzed by the fear of “intervening too much” and lacking an alternative vision with solutions for the facts.

Unlike many diplomats, he ventured into besieged enclaves. He spoke with Serb and Bosniak leaders, but he also sat with Bosnian families surviving on rationed hope. He felt he had arrived too late at a sad moment in history.

The horror struck him head-on. And with it, the realization that the humanitarian mandate had unbearable limits. He understood that without real political will, aid was merely a bandage in the midst of massive bleeding. It was a failure he felt personally.

A Pragmatist with a Conscience

Vieira de Mello was not a vigilante. He was a realist with an ethical compass. He knew he had to negotiate with the perpetrators if it meant delivering food or protecting a convoy of displaced people. But he never confused that with legitimizing them. His dilemma was not between good and evil, but between greater evil and unavoidable evil. It was not about choosing between the ideal and the possible, but between the possible and the intolerable.

Bosnia left him with scars that never faded. It was there that he understood, more than anywhere else, the void between international rhetoric and real tragedy. And it was also there that he began to forge the conviction that peace is not an act of imposition, but of negotiation with the unacceptable, to prevent the irreversible.

In Bosnia, Vieira de Mello did not save the world. But he refused to look away, and in that war, that alone made him different.

Kosovo: Peace Without Winners

Kosovo was a wounded land when Sérgio Vieira de Mello arrived in 1999. NATO’s bombings had ceased, but the war had not ended: it had simply changed form. Ethnic cleansing turned into revenge, and the supposed liberation gave way to a new kind of chaos. For many, the conflict had been between good and evil. For Sérgio, it was something else: a war where there could be no peace unless the defeated were also included.

An Impossible Mission?

Vieira de Mello arrived in Kosovo as part of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission (UNMIK), with the difficult task of overseeing the post-conflict transition. His role was to coordinate humanitarian aid, the repatriation of refugees, and the reestablishment of civil authority amid explosive ethnic tensions.

Kosovar Albanians were returning by the thousands, often with vengeful intentions toward local Serbs. The latter’s homes were burned, looted, and the elderly expelled. Kosovo was on the brink of a second war, but this time, without cameras.

Sérgio understood what many in the international community preferred to ignore: selective justice is not justice; it is fuel for hatred.

Sérgio Vieira de Mello was also the coordinator of the UN’s humanitarian operation on the ground and worked directly with the World Food Programme to assist the most vulnerable. He visited refugee camps in neighboring countries like Albania and North Macedonia, as well as return areas in Kosovo, to assess needs and show international support. These visits reinforced confidence in the repatriation process during the critical phase between June and October 1999.

A Peace That Does Not Humiliate

As in East Timor or Bosnia, his approach was to listen first, judge later. He held meetings with both Kosovar leaders and local Serb representatives. He refused to reduce the conflict to a binary narrative. For him, reconciliation was not about rewarding the guilty, but preventing resentment from becoming doctrine.

The Return of the Invisible

One of his most committed efforts was the safe repatriation of displaced minorities, especially Serbs and other forgotten communities. He knew he would not achieve complete success, but he also knew that true peace is measured by the security of the weakest, not the strength of the strongest.

Sérgio’s work was key to ensuring the return of 800,000 Kosovar Albanians without reigniting the conflict, despite the notable implications.

Facing the Geopolitical Chessboard

Kosovo was also a lesson on the limits of the UN against the hard power of states. NATO’s intervention had been unilateral. Tensions between Russia, the United States, and Europe were at a boiling point. The UN was once again both actor and hostage.

Sérgio was not deluded. He knew his margin of action was narrow, but he moved with cunning and humanity, convinced that even within international cynicism, there was room for an ethic of care.

In this vein, he worked closely with NATO forces (KFOR) to demilitarize zones, disarm insurgent groups like the KLA, and protect returnees, especially in a context of persistent ethnic tensions between Albanians and Serbs. All this without ceasing to be critical of their actions and without losing dialogue with the Serb community.

The Permanent Dilemma

Kosovo was not a closed case. It was another stage in his learning that peace is not decreed, it is negotiated—and often paid for with difficult silences and uncomfortable decisions.

In Kosovo, as in so many other places, Sérgio faced the dilemma that marked his career: How to defend principles without becoming an obstacle to stability? How to protect victims without creating new perpetrators?

Vieira de Mello left no formulas. He left gestures. Concrete decisions that saved lives amid chaos. And a radical idea: that peace is not achieved with winners and losers, but when everyone can stay home without fear of their house being burned.

After his brief four-month mandate, he handed over UNMIK leadership to Frenchman Bernard Kouchner in October 1999, later assuming a key role in East Timor (UNTAET).

Though his time in Kosovo was short, Vieira de Mello laid the groundwork for international administration, standing out for his ability to manage complex crises. His work paved the way for institutional reconstruction and initial stabilization, vital elements for UNMIK’s long-term mandate.

Iraq: The Foretold End

In 2003, he accepted his final mission without knowing it: Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General in Iraq, following the U.S. invasion. It was not his ideal destination. He had said he did not want this mission. The war seemed illegal to him, poorly planned, arrogant. But he accepted. Because he thought someone had to be there to protect civilians. To put a human face between the tanks and the ruins.

In August 2003, Saddam Hussein had fallen after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, but what remained was not the promised freedom, but a power vacuum where fear, resentment, and weapons coexisted.

The Diplomat Against the Current

Sérgio opposed the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Not because he sympathized with Saddam Hussein, but because he believed the military action violated international law and weakened the role of the UN Security Council.

Vieira de Mello was not convinced of the war’s legality. He had been critical of the invasion, of its “shock and awe” logic, of the arrogance of those who thought democracy could be built with bombs and privatizations. But he also understood something else: the UN could not ignore the human wreckage left by geopolitics.

He accepted because he thought he could make a difference. That his presence would serve as a humanitarian shield. That Iraqis would see in him something different from the uniforms of the occupiers. That sometimes neutrality is not staying on the sidelines, but offering an alternative.

The UN at Ground Zero

From the Canal Hotel in Baghdad, Vieira de Mello began moving with his usual style: listening before speaking, walking among the people, meeting with local actors, avoiding excessive security. His goal was not to represent the international community but to give Iraqis a voice in their own reconstruction.

An anecdote tells that upon arriving in Baghdad, Sérgio demanded that U.S. occupation troops withdraw from guarding the UN diplomatic headquarters, to avoid Iraqis associating the organization with the occupation.

But the situation was unsustainable. Insurgent militias were beginning to emerge. The UN lacked sufficient protection. And worst of all: it was no longer seen as a neutral actor, but as part of the occupation, simply for being there.

Vieira de Mello sensed something was wrong. He felt it. And yet, he stayed. He tried to design an election timeline with the goal of foreign troops leaving Iraq as soon as possible, all despite the little political will he observed.

Vieira de Mello openly criticized several decisions by Bremer, the U.S. envoy in Iraq: the dissolution of the Iraqi army, the mass purge of the Ba’ath Party, the abuses by U.S. occupation troops against the local population, and the centralization of power in foreign hands.

The abuses by U.S. troops were documented by Sérgio and his team, who sent reports to the Security Council and publicly criticized such actions.

Sérgio believed the inclusion of former officials and tribal leaders was essential for stability. The United States, meanwhile, bet on a total redesign from exile and exclusion. For Vieira de Mello, this only fueled insurgency and conflict.

His strategy was one of local legitimization, not external imposition. That’s why he met with Shia religious leaders, Sunni tribes, academics, and Iraqi NGOs. He was not looking for allies; he was looking for real actors.

This approach did not please everyone. To the insurgents, it made him a military target. But to some U.S. officials, it made him unpredictable and an obstacle.

Years later, his legacy remains a thorn in the side for those who believe interventions can be useful and designed from afar, ignoring and failing to listen to communities and their realities.

August 19: The Rubble of the International System

At 4:30 p.m., a truck bomb loaded with artillery explosives detonated in front of the Canal Hotel. The target was clear: the UN headquarters. The attack was orchestrated by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s group, which would later become part of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. The message was brutal: there are no protected zones anymore. No safe diplomacy.

The wing where Sérgio’s office was located collapsed. He was trapped in the rubble, gravely injured. For hours, he asked rescuers to attend to others first. He died without knowing the attack had claimed 22 more lives, including his friend and advisor Arthur Helton. One of his last requests while speaking to rescuers under the rubble was that they not suspend the UN Mission, no matter what happened.

A Turning Point in Humanitarian Aid History

The attack on the Canal Hotel marked a breaking point for the United Nations. For the first time, a symbol of global neutrality had been deliberately attacked as a military target. Since then, humanitarian missions began fortifying themselves, hiding behind walls and protocols. The direct contact with people that was Sérgio’s hallmark became nearly impossible.

It was also a symbolic blow: Vieira de Mello’s practical idealism seemed to die with him under the rubble of violence.

Why Did He Go to Iraq?

That is the question many still ask.

Some say it was pressure from Kofi Annan. Others, that it was a moral debt. Maybe it was voluntarism. Maybe he thought his mere presence would change the course of the disaster. But it was probably what it always was: the belief that the UN had to be where people suffered, even if the world did not want to look.

“In Iraq, where he spent the last months of his life, Vieira de Mello worked day and night to help the Iraqi people regain control of their destiny and build a future of peace, justice, and independence. It is tragic that he gave his life for that cause, along with others who, like him, were devoted servants of the United Nations,” emphasized Kofi Annan in remarks after his death.

The Flame That Does Not Extinguish

In a tribute, Kofi Annan called him “the most human face of the United Nations.” For Samantha Power, in her book Chasing the Flame, Sérgio’s actions were not about saving the world, but refusing to accept its darkness without doing anything.

Iraq was his final act. Not the most successful, but the most revealing: in a world dominated by force, there are still those who believe in the power of words, gestures, peacebuilding, and presence.

Vieira de Mello was not a martyr. He was a diplomat who went where no one else wanted to be. Who died doing what he always did: talking to everyone, even the violent, so that at least some could live in peace.

He was not a hero. He was a man who believed until his last breath under the rubble that even in the worst scenarios, something could be saved.

The attack marked a before and after: humanitarian workers were no longer untouchable. War no longer distinguished between weapons and words.

The Price of Peace

To speak of Sérgio Vieira de Mello is to speak of the grays of history. He was not perfect. Perhaps at times he was too flexible. At times, too forceful. But no one can say he did not risk everything. His legacy raises uncomfortable questions about how far one can or should go to save lives.

Sérgio Vieira de Mello was not a star, not a personalistic figure, nor a hero of epic films. Sometimes maybe he was too insistent. Sometimes, too idealistic. His actions were not free of criticism; he was accused of “collaborating” and being “complicit” with atrocities and authoritarian leaders. But it was his approach that allowed the foundations for peace to be built in many nations of the world, thus saving countless lives—those often left invisible behind a number or under the simplistic concept of “collateral damage.”

As Kofi Annan (2012) said, he was “the diplomat who did the right thing even when it wasn’t popular.” His legacy raises uncomfortable questions:

- Can peace be made without talking to the violent?

- Must justice wait for reconciliation?

- How much justice can be sacrificed to prevent more war?

- What is the moral cost of peace?

He did not have all the answers. But he had the courage to face them. And in a world that often looks away, that alone made him different.

In Chasing the Flame, Power writes of Sérgio and his life (2008): “Chasing the flame is not about saving the world, but refusing to let it go out.”

In times like the present, when the international order is fracturing and talk of reform is in the air, when diplomacy seems unpopular and the word “peace” already sounds like a utopia to many, Sérgio’s actions are a manifestation of the conscience of a global society emerging from the ashes of war.

For Venezuela, Sérgio’s story and actions resonate in a special way. If only the actors in the conflict could look to his record as a compass to find answers in an extremely difficult and complex reality. It would be very useful for them to engage with his legacy; they might find some answers that could surely be useful for Venezuelan society, no matter how utopian that sounds in the current context.

I would like this small reflection on Sérgio’s life and his lessons for Venezuela to reach, in some way, the country’s various political actors, regardless of their affiliation—especially those who still see peace as an opportunity, not an obstacle or a cost.

Our country has been trapped for decades in a power conflict that has been excessively costly for the population. Of course, this is not about making comparisons or equivalences of any kind, just as Sérgio never did in any of the conflicts where he worked to mend what was broken.

Peace can be an opportunity, but only if it is built—and that will not be easy or an epic chapter. It will, perhaps, be costly and very complex. But if we think about it, we understand it is worth it, because only then can the foundations be laid for that future country where no one has to leave or live in fear for what they believe.

I would also like the international community interested in helping Venezuela to look to Sérgio Vieira de Mello as a reference for what they could do if their goal is truly to help Venezuelans. It is not through imposition, coercion, suffocation, or the degradation of Venezuelan identity that they will be able to help our country.

Peace is also not a decree or an imposition by an institution. Peace is a construction that demands agreements and guarantees for all.

Perhaps hoping these words reach those responsible and the leaders is asking too much. Maybe it is too ambitious of me to ask that, in these 26 years, they might find in Sérgio Vieira de Mello a guiding light to build an alternative future, different from the harsh reality we have had to endure.

It has been 26 years of conflict—meaning this began before many of us, including myself, were even born. Inheriting a conflict has many implications for us, the youth. We are the ones who stand to lose the most if it continues, and at the same time, we are the ones who stand to gain the most if peace finds a way as the driving force of that future country we will all share.

Personally, I found in Sérgio Vieira de Mello, at the age of 12, a role model when I discovered his story and his life. He was one of the people who made me passionate about diplomacy and peacebuilding. A person who proved that these things can indeed help resolve conflicts. It has happened before, and Venezuelans are not an exceptional case; that gives me hope that one day we can achieve it too. I only wish that those who today have the power to decide the future and lives of millions of Venezuelans could also find in his story and actions a reference to guide them in a moment where answers are scarce and questions overwhelm us.

But this reflection is not just for the political elite; it is also for every citizen and person interested in a better future for the country. Peacebuilding starts from the ground up, and it is the people who are the main protagonists in making it real and in demanding a sustainable agreement for the coming decades and generations of Venezuelans yet to come.