Venezuelans deported from the United States to El Salvador are escorted off a plane by Central American security forces to be imprisoned in the CECOT “mega-prisons.” Photo: El Salvador Press Secretariat.

Guacamaya, March 18, 2025. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio threatened Venezuela with “new, severe and escalating sanctions” on Tuesday, to force the country to accept deportation flights.

However, the government of Nicolás Maduro had already agreed to resume deportations. The latest flight, scheduled for Friday, March 14, was reportedly postponed, and the Venezuelan migrants were instead sent to El Salvador, accused of belonging to the Tren de Aragua, according to sources consulted by Guacamaya.

In this case, Rubio appears to be attempting to send Venezuelans to third countries to cut off direct communication channels between Caracas and Washington DC, while escalating economic and political pressure against Venezuela.

If Venezuela Already Accepted Repatriations, How Did We Get Here?

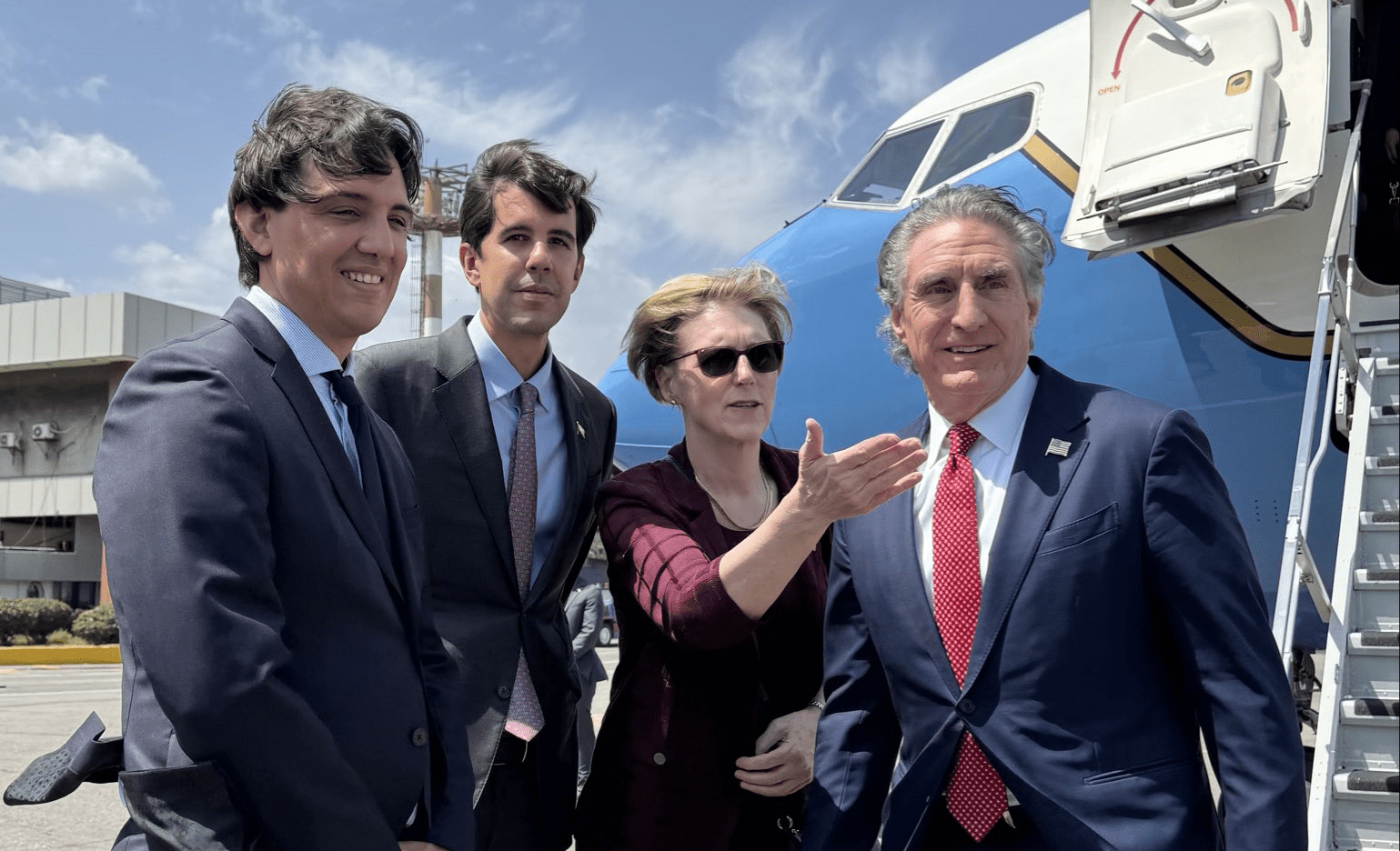

President Trump’s special envoy, Richard Grenell, announced on January 20 that direct communications with the Venezuelan government had been opened. Shortly after, on January 31, Grenell arrived in Caracas to meet with Nicolás Maduro.

It was agreed that the state airline Conviasa would pick up Venezuelan migrants detained in the U.S. According to a source in the Trump administration, it was the Maduro government itself that offered to resume the flights and cover the costs under the “Plan Vuelta a la Patria” (Return to the Homeland Plan).

After the revocation of the Chevron license, relations between the two governments became tense again. It is worth noting that the end of the license was pushed for by Rubio allies, including Florida House representatives Carlos Giménez, María Elvira Salazar, and Mario Díaz-Balart, according to Axios.

However, on March 13, Grenell announced that repatriation flights between the U.S. and Venezuela would continue under the same conditions. The next flight was scheduled for the following day. This was confirmed by his Venezuelan counterpart, Jorge Rodríguez, and Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello, who stated that there would be a flight to El Paso. The flight was reportedly suspended that day due to a storm.

Conviasa flights would only be licensed to land at certain military airports in the U.S., as civilian or commercial airports posed the risk of being seized by Venezuelan state creditors.

When it was revealed that the El Paso repatriation flight would be postponed, Marco Rubio’s team allegedly leaked to the press the intention to send Venezuelans to El Salvador. The leak was published by AP.

Rubio’s first international tour was through Central America, where he reached agreements with countries like Panama, Costa Rica, and El Salvador to accept deportees from third countries, including Venezuela. However, Ambassador Grenell was already in talks with Caracas to resume direct repatriation flights.

According to a statement by Jorge Rodríguez on Tuesday, the same migrants who were in El Paso were the ones sent to El Salvador. These individuals were accused by the White House of belonging to the Tren de Aragua criminal organization and have been interned in the Central American country’s “mega-prisons.”

The CECOT facilities, designed by Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, were created to punish thousands of members of local gangs, known as “maras.” Human rights organizations have denounced torture and various legal violations in these centers.

According to AP, the Trump administration would be paying El Salvador at least $6 million for the first group of 238 deported Venezuelans. In turn, Bukele announced that the migrants themselves would be forced to work to cover the costs of their own imprisonment.

Although the 238 Venezuelans have been accused of belonging to the Tren de Aragua, no evidence has been presented. The U.S. State Department itself refused to provide evidence when requested in writing by Guacamaya.

101 of the deportees sent to El Salvador were reportedly expelled solely for entering the U.S. illegally, raising doubts about their involvement in any criminal organization. In a statement under oath, a U.S. immigration officer stated that many of these migrants “had no criminal records.”

The officer also stated that, given the difficulty in uncovering criminal histories for several of the migrants, “the lack of specific information about each individual actually highlights the risk they pose. It demonstrates that they are terrorists with regard to whom we lack a complete profile.”