Political scientist Michael Paarlberg was the Latin America advisor to Bernie Sanders’ 2020 campaign.

Guacamaya, August 26, 2025. Michael Paarlberg is a Political Science professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. As a progressive and a foreign policy expert, in 2020 he served as the Latin America advisor to Senator Bernie Sanders’ campaign. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Center for International Policy and an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies.

We ask him about U.S. policy towards Venezuela, especially from his perspective as a progressive. He has voiced his disagreement with both the strategies of the Trump and Biden administrations, arguing they are working on wrong assumptions. Sanctions have to go, but we cannot be naïve about Nicolás Maduro.

Q: In an interview with eldiario.es, you stated that “Venezuela is a very strange country. I tell my students that it’s not really a Latin American country, but rather a Middle Eastern petrostate located in Latin America.” What do you mean?

A: It is an ongoing frustration of mine that so much U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America and the Caribbean is seen through the lens of countries which are not very representative of the region. For most of the Cold War era it was Cuba, but for the past 25 years it has been Venezuela. Venezuela is not like the rest of Latin America. It is a petrostate, a founding member of OPEC. And while there are other oil and gas producing countries in the region, none have economies as dependent on oil—and vulnerable to global oil price fluctuations—as Venezuela’s.

As in other petrostates in the Middle East, Asia and Africa, this resource curse produces economic bubbles and collapses. It incentivizes corruption, patronage, and autocracy. This oil economy creates government subsidies and institutions that don’t exist in other countries like Mercal. No other country in the region puts generals in charge of distributing diapers. And yet Washington imagines that Venezuela is representative of Latin America as a whole, or the Latin American left, or Latin American autocracies, and shapes its foreign policy accordingly, while ignoring much bigger and more important actors like Brazil. In reality, politically and economically, Venezuela has more in common with Iran than with Colombia or even Cuba.

“In reality, politically and economically, Venezuela has more in common with Iran than with Colombia or even Cuba.”

Q: The administrations of Donald Trump and Nicolás Maduro have carried out an exchange between migrants detained at the CECOT in El Salvador and Americans imprisoned in Venezuela. Could this approach set a precedent in relations between Washington and Caracas, and what is your assessment of this?

A: One thing that many people in the U.S. have not understood is that it cannot unilaterally deport people to another country. It has to have a deportation agreement with that country. If it has hostile relations with a country that is producing many migrants, as with Venezuela, this complicates things: it gives migrants stronger claims of asylum and it makes it harder to deport them. It also empowers the migrant-producing country to negotiate certain concessions from the U.S.

Maduro correctly calculates that the migrant exodus which his mismanagement produced—and was exacerbated by U.S. sanctions—has become an asset to him, as it rids the country of potential dissidents, gives a substantial boost to the economy through remittances, and puts pressure on the U.S. to come to the negotiating table. He also calculates that he doesn’t have to abide by the terms of those negotiations, as he did with the fraudulent election. However, Maduro is still economically vulnerable, and Trump is not willing to let Maduro hold all the cards. Thus, the Trump administration is taking a mixed approach: publicly threatening military action while privately making some concessions which also benefit U.S. corporate interests. This appears to be the precedent for diplomatic relations going forward: no less antagonistic, and could still veer into conflict at any moment, but a relationship that still allows for negotiation.

“Most corruption looks more like Odebrecht than Tren de Aragua.”

Q: A group led by Joseph Humire listed alleged crimes committed by the “Tren de Aragua” in the United States. However, InsightCrime has detected multiple false entries. Several intelligence agencies have also denied claims by the Trump administration about the criminal group, including that it is being directed by Maduro. Do you think a false narrative has been constructed about the Tren de Aragua? Is it intended to attack the rights of Venezuelan migrants?

A: It is not only private intelligence analysts that have contradicted the Trump administration’s claims about Tren de Aragua (TdA), it was Trump’s own Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard, who was later pressured to walk back her statements.

The exact relationship between the gang and the Maduro government is murky, and there have certainly been pacts between TdA and certain government officials such as Tareck El Aissami. There isn’t evidence, however, that the gang’s activities are being directed from Miraflores (Venezuela’s presidential palace). The murkiness of their state connections allows the Trump administration to exaggerate them for the purpose of pressuring the Maduro government and to facilitate deportations by tying migrants to gangs and thus to “terrorism.” It also allows Maduro to create a scapegoat and make show arrests of individuals like El Aissami to distract from the endemic nature of his government’s corruption, most of which is more pedestrian than gangs or drugs: procurement fraud and money laundering. Most corruption looks more like Odebrecht than Tren de Aragua.

Q: Within the Trump administration, there appear to be two different approaches to relations with Venezuela. One advocates for “maximum pressure” to achieve regime change, with sanctions and even the possibility of military action. Meanwhile, the other proposes a more pragmatic and negotiating approach. What do you think leads them to disagree and even publicly contradict each other?

A: Trump’s foreign policy is divided between two camps, the neocons and the nationalists. This reflects broader divisions within Trump’s base: between traditional Republicans, many holdovers from the Bush administration who are more ideological and interventionist; and those who are loyal only to Trump, think the Iraq War was a mistake, and think foreign policy should serve to make business deals.

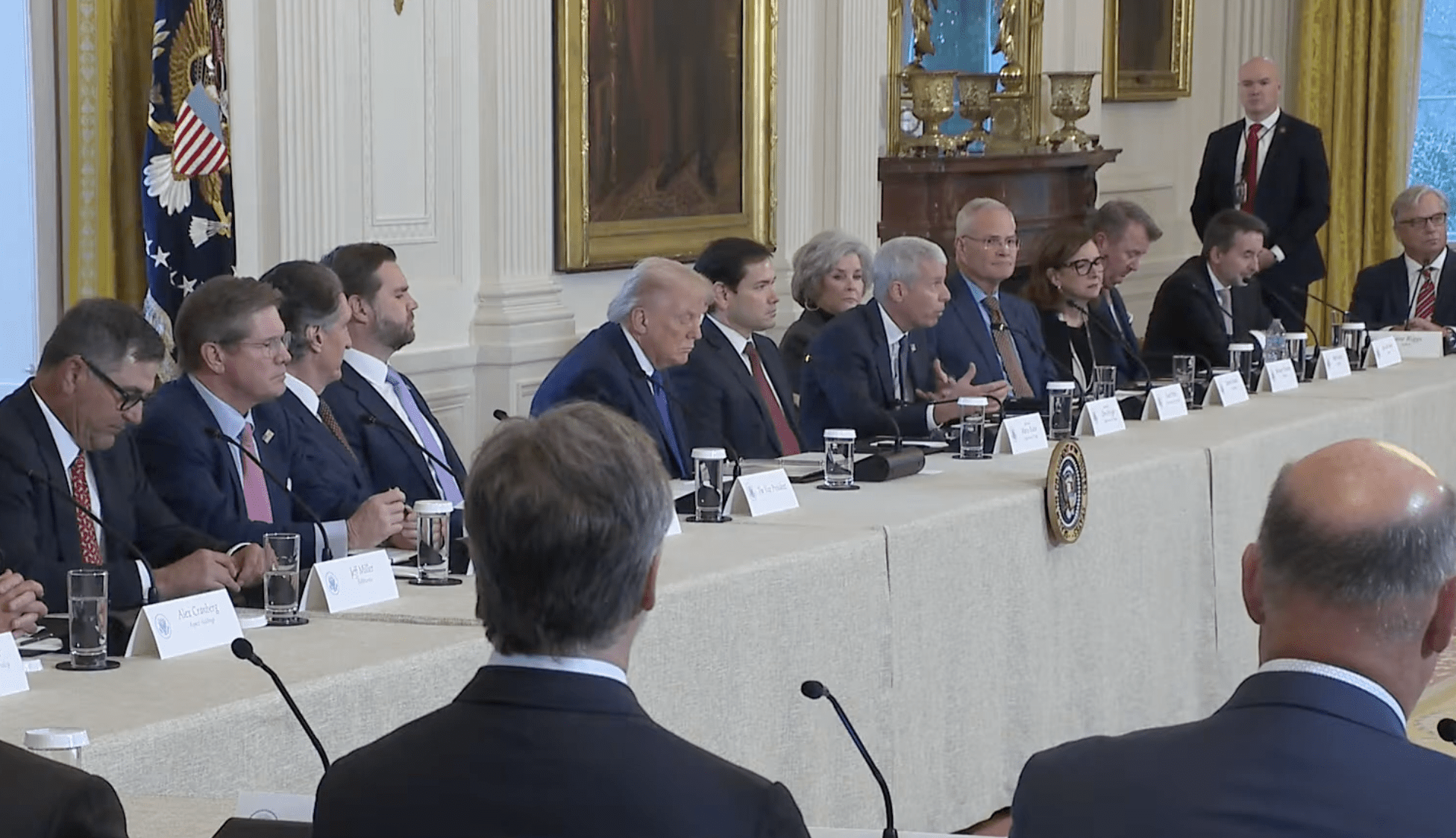

Marco Rubio is a representative of the neocon camp. Though he pledges fealty to Trump like everyone, he represents the hawkish Cold War era approach that favors maximum pressure sanctions and regime change. Yet his power to craft foreign policy is undermined daily by Trump’s announcements that often contradict Rubio. On the other side are figures like Ric Grenell and Steve Witkoff, both special envoys with vague powers, and internet personalities with no official position like Laura Loomer. Grenell, along with Loomer, have been pushing for a deal with Maduro, likely to benefit their own financial interests, and those of the corporate allies they represent.

This division benefits Maduro, as he can play the two sides against each other, as he did when both Rubio and Grenell were negotiating with Jorge Rodriguez at the same time, unbeknownst to either of them, and offering different deals. The Chevron license renewal indicates that despite the Trump administration’s threats of military force, the dealmakers have the upper hand for now.

“The unfortunate conclusion is that to convince someone to give up power, you have to offer them something more attractive than a prison cell.”

Q: What approach would be more effective and just to bring about political change in Venezuela? Creating incentives through negotiation, or forcing Maduro out with maximum pressure?

A: We can only look to the result of the economic embargo on Cuba, and the longevity of the regime there, to see that economic sanctions do not work for the purposes of regime change. And not just Cuba: look at the survival of regimes in Iran, Russia, North Korea, nearly any country the U.S. has sanctioned.

If nothing else, they give an autocratic government a convenient scapegoat to blame for problems of their own making, and an excuse to crack down further on dissent. At the same time, they do cause great suffering, but that suffering is borne by regular citizens, most of whom are likely to oppose the regime. If the goal is to incentivize an autocrat’s exit, maximum pressure has the opposite effect. So too do threats to prosecute or kill autocrats. What dictator would willingly step down if they know that the likely outcome is prison or death? Maduro saw what happened to Muammar Qaddafi, and drew his own conclusions.

There is extensive academic scholarship on what worked to speed the transitions to democracy in the 80s and 90s in Latin America, by political scientists like Guillermo O’Donnell. Those few that step down are only coaxed to do so by promises of amnesty, or tricked into a clean election (such as Pinochet), or are forward thinking enough to reform their parties so their successors can contest elections again (Mexico’s PRI, and Mongolia’s People’s Party are rare examples).

These were negotiated exits that involved amnesty deals and promises for the military to retain certain powers. These were deeply frustrating to the victims of those regimes. Some of those dictators and their agents were eventually prosecuted. There have been examples of dictators and their officials who were offered amnesty, and had it overturned by legislatures or judges later, as in Chile and Argentina. But the unfortunate conclusion is that to convince someone to give up power, you have to offer them something more attractive than a prison cell.

Q: A study recently published in The Lancet claims that unilateral economic sanctions have an effect on mortality similar to that of war. What is your perception of “sectoral” or “economic” sanctions? What role do they play in a progressive foreign policy for the United States?

A: One should be clear when using euphemisms like “sectoral sanctions” on what they mean. If a country has only one sector, as does Venezuela, this amounts to a sanction on the entire economy, and thus on ordinary people struggling to survive. Even the embargo on Cuba is fairly “leaky,” in the sense that almost no other country recognizes it, and there are many exceptions to it, even for the U.S.

It is probable that the U.S. sanctions on Venezuela have killed a great number of people, more than in Cuba. Even if they were an effective political tool—which they are not, as Maduro’s continued rule demonstrates—they would be morally unjustifiable. They should be lifted unilaterally, not as a gift to Maduro—he would lose his most useful scapegoat—but as a show of solidarity to the Venezuelan people, whose suffering the U.S. professes to care about. There are other tools, including personal sanctions, which can more effectively target individual leaders, and criminal investigations, like the kind that brought down Juan Orlando Hernández.

The perpetuation of maximum pressure sanctions and embargoes despite the lack of regime change raises another question: if regime change is the true goal of those measures, or whether they serve another purpose: to provide leverage to make a deal, or politically, to maintain a convenient foreign villain for the U.S.

“There was a general naivety by Biden and his foreign policy team. The genocide in Gaza is the result of Biden’s all carrot, no stick approach.”

Q: Juan González, former senior director for the Western Hemisphere at the National Security Council under Biden, stated in an interview with Guacamaya that: “When we took office, it was already evident to the region that policy toward Venezuela was being dictated by the political dynamics of South Florida, not by a serious plan to restore democracy.”

Do you think the interests of Venezuelan and Cuban exiles in Florida are aligned with U.S. foreign policy interests? How have they managed to have such influence?

A: The South Florida Cuban American lobby has been one of the most successful lobbies in U.S. history. Though I do not share their policy goals, I have to give them credit for their effectiveness and discipline. There are very few issue areas in which a tiny, organized group commands a policy that is opposed by, and contrary to the interests of the vast majority of Americans. I also sympathize with people who have fled their homeland due to a dictatorial regime and wish to see change, even if these policies are counterproductive to their goals.

Today’s Venezuelan American diaspora is smaller but has coordinated with the Cuban American lobby to push for hawkish policies. However, just as Venezuela is eclipsing Cuba as Washington’s bête noire, two less favorable political trends are undermining the influence of the so-called Magazolanos. First, we have seen Florida shift from becoming a swing state that decides elections to a solidly Republican state, one which Democrats no longer believe they need to win, or can win. It used to be said one cannot win the presidency without Florida; Biden’s win in 2020 proved otherwise. Second, we are seeing a post-Cold War shift in attention from dictatorships to migration. Today, U.S. foreign policy is driven more by a fear of migration than a fear of “communism.” Thus, the states that have greater importance are shifting from Florida to border states like Arizona and Texas. I expect we will see more incentives to make deals with dictators, and we can see this in Venezuela policy and the diminished power of hawks like Rubio.

With respect to Juan, it was good that he was willing to take a new approach, and he was correct to diagnose the shifting political winds that gave Biden an opportunity to do so. However, the Biden administration’s approach to Venezuela was naive, and the failure of the Barbados Agreement demonstrates this. They recognized that Maduro wants sanctions relief, however they missed that he prioritizes his own political survival above all else, including above the wellbeing of the Venezuelan economy or its people.

This reflects a general naivety by Biden and his foreign policy team. It was not just about Maduro. The administration coddled Bukele as he actively dismantled El Salvador’s democracy. Most tragically, in Israel, they gave a blank check and unlimited weapons to Netanyahu, believing that he was acting in good faith. Like Maduro, he is a corrupt figure who only values his own political survival, and needed to keep a war going to stay in office and out of prison. You need to understand the domestic political dynamics and incentives of any foreign leader, and you need to use both carrots and sticks. The genocide in Gaza is the result of Biden’s all carrot, no stick approach.

“Sectoral sanctions should be lifted unilaterally, not as a bargaining chip, simply on the basis of alleviating human suffering.”

Q: You were Bernie Sanders’s advisor on Latin America during his 2020 campaign. What key elements did you propose regarding Venezuela at the time? Which ones would be useful?

A: I cannot speak for Senator Sanders, so I can only speak about my own views and advice which I shared with him during the election and since. During the campaign, Senator Sanders was targeted by every other candidate in the Democratic Party who viewed his popularity as a threat, and they sought to brand him as a radical and sympathizer with dictators, which was not true. If you recall, he called Maduro a “vicious tyrant” during his campaign. Neither he nor I have any illusions about who Maduro is. Incidentally, this is in contrast to many Democrats, who seem to believe if you simply reason with a bad faith actor, they can be convinced to be liberal democrats, and to Republicans, who think you can get results simply through threats of force. But the media focused only on the label “socialist,” which in the U.S. basically just means you support universal healthcare. It means something very different in Venezuela, just as it does in Chile or in France.

My view has been that the guiding principle should be solidarity with the Venezuelan people. It should not be regime change. Even those who believe that regime change would be a better outcome should recognize that elections by themselves will not lead to regime change, because Maduro will steal elections. However, it is also clear that maximum pressure and sectoral sanctions do not lead to regime change either, and are inhumane. They should be lifted unilaterally, not as a bargaining chip, simply on the basis of alleviating human suffering. And if elections were to be viable in the future, there needs to be much more groundwork done, with guarantees of effective monitoring and campaigning.

Q: Which multilateral efforts could the U.S. support?

A: I also recognize the U.S. does not have much credibility as a neutral actor, and there is a greater role to be taken by other countries. It is true that efforts by Brazil, Mexico and Colombia have not been taken seriously either. But there is a role for the U.S. to play to make their proposals more viable by applying targeted, selected pressure, and at the same time offering Maduro a way out.

Q: With this year’s parliamentary and local elections, the opposition has split in two: between those seeking confrontation with Trump’s help; and those proposing to participate in elections and negotiate with Maduro, even though they remain in the minority. What can progressive forces in the U.S. do to help Venezuela’s struggle for democracy? Could or should they formulate an alternative approach to “maximum pressure”?

A: I believe no U.S. administration, nor U.S. progressives, should have illusions about Maduro. Given his deep unpopularity, and the way he sees holding on to power as a question of life or death, it is improbable that any election under this government will be free or fair. For this reason, I believe that the hyper focus on elections as the goal is likely to be a failed strategy, as the Biden administration’s approach shows.

It also is important for the U.S. not to pick sides in internal political disputes, especially for an opposition as historically divided as Venezuela’s. There are other actors in Venezuelan civil society, apart from specific opposition leaders, who could use support. Some of those groups have engaged with the regime, others have not, but some have achieved piecemeal gains that have improved state services, diminished repression, and made daily life incrementally better. It is not my place to tell the Venezuelan opposition, or its people, what to do. But I predict that democratic change will be gradual, and it is better to play a long game than to believe promises of quick fix solutions from maximum pressure and the like. These are fantasies told by U.S. politicians like Trump to win elections in the U.S., not serious plans to help Venezuelans in Venezuela.