Fabbiana Lamboglia holds a degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics from the University of Navarra. She is an IRENA Youth Delegate and a former trainee in the Private Sector and Trade Finance Operations Department at the OPEC Fund for International Development.

Guacamaya, November 3, 2025. Oil has historically been Venezuela’s most influential and alluring natural resource — a source of wealth, but also of inequality, geopolitical tension, and international sanctions. Yet, in a world steadily advancing toward an energy transition, one inevitable question arises: what role will Venezuela play in this new post-oil era?

The energy transition is neither a distant phenomenon nor a passing global trend; it’s a process that is already reshaping economies, geopolitical relations, and development opportunities around the world. In this new context, Venezuela remains tied to an extractivist model that is running out of time. The decline of its oil industry —worsened by sanctions, lack of investment, and commercial isolation— has drastically reduced national production. Still, the country holds immense solar and hydropower potential that could pave the way for a complete reinvention of its energy matrix. That path, however, requires much more than natural resources; it demands overcoming the political, institutional, and cultural challenges that will ultimately define Venezuela’s true energy future.

Transforming a Matrix in Crisis

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, Venezuela’s total energy supply fell by nearly half (-47.5%) between 2016 and 2021, reflecting both the country’s economic contraction and its loss of productive capacity. Non-renewable energy dropped by 52.9%, while renewable energy decreased by only 7%. This does not indicate a conscious energy transition, but rather that Venezuela is producing and consuming less energy overall — and within that reduction, clean sources have gained relative weight.

In that same report, the current composition of Venezuela’s total energy supply is: oil (38%), gas (41%), and renewables (21%). Although fossil fuels still dominate, the renewable share has grown in relative terms due to the decline in thermal generation and the sustained operation of hydropower facilities. It’s a delicate balance that speaks more to decline than to real transformation.

A Clean Grid in a Fossil-Dependent Nation

In 2023, data from Low Carbon Power indicated that around 78% of the electricity generated in Venezuela came from low-carbon sources, while solar (0.01%) and wind (0.02%) remained marginal. Fossil fuels, on the other hand, account for a little over one-fifth of total electricity generation, with natural gas (14.6%) as the main component and unspecified fossil fuels (7%) making up the remainder of thermal generation.

At first glance, it might look like an environmental success story. Yet the picture changes when seen in context: Venezuela’s electricity may be mostly clean, but the country’s overall energy use —from transport and industry to households— still relies about 80% on fossil fuels.

Hydropower Dominance and Structural Vulnerability

Venezuela has one of the cleanest electricity matrices in Latin America, but this “strength” depends almost entirely on a single source: hydroelectric power. Around 99% of its renewable generation comes from the Guri system and other associated dams, while solar, wind, geothermal, or bioenergy sources do not even reach one percent of the total.

This lack of diversification is a structural vulnerability. The Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Central —known as the Guri Dam— is one of the largest in the world and forms the backbone of the national electrical system. Any alteration in its water levels or maintenance has an immediate impact on the country’s stability. Climatic phenomena like El Niño, which reduce rainfall, or the lack of investment and technical management, have caused massive blackouts that affected the economy and social well-being.

The lesson is clear: an energy mix isn’t judged solely by its cleanliness but by its resilience. Venezuela can claim that its electricity is largely renewable, but if it relies on a single vulnerable source, that claim loses weight in the face of the real challenges posed by climate change.

Untapped Potential

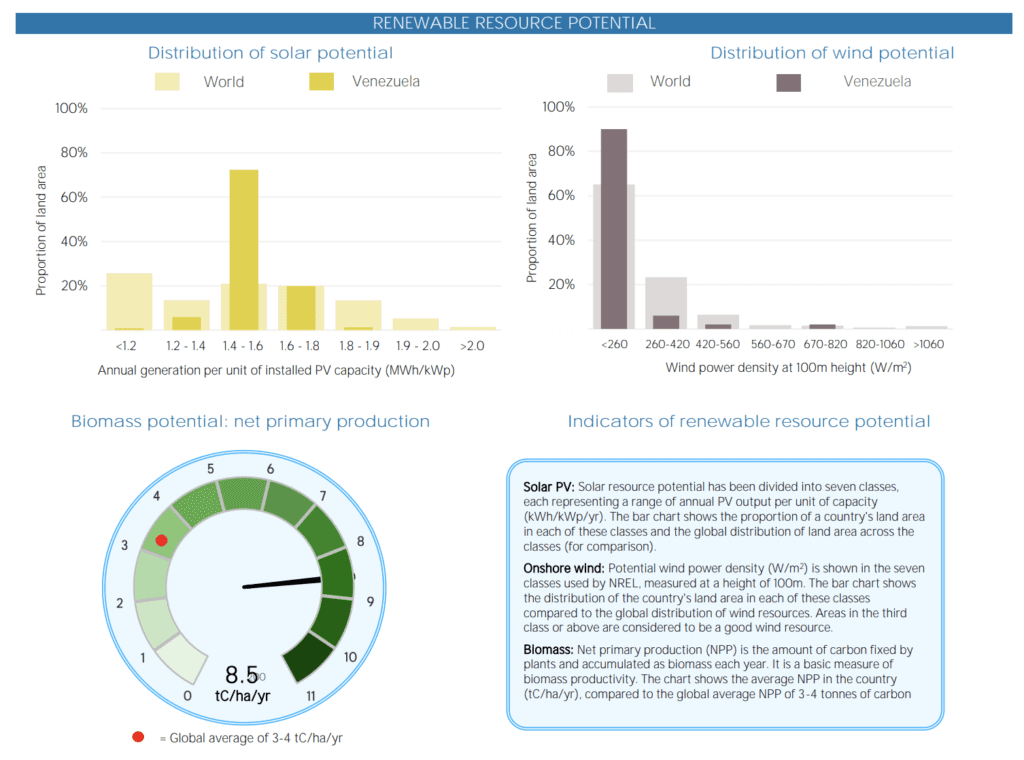

According to estimates from the International Renewable Energy Agency, over 80% of Venezuela’s territory boasts an average solar yield of 1.6 to 2.0 MWh/kWp per year — a figure that significantly exceeds the global average of around 1.2 MWh/kWp. This means that much of the country enjoys consistent, high-quality solar radiation, particularly well-suited for photovoltaic generation.

As for wind resources, areas such as the Paraguaná Peninsula in Falcón State and La Guajira in Zulia State show wind power densities ranging from 420 to 670 W/m² at 100 meters of height — values that are also well above global averages. These conditions place Venezuela among the territories with the greatest technical potential in the continent for the development of large-scale solar and wind farms, an abundant resource that remains underutilized in light of the country’s current and future energy needs.

Education and Innovation: The Invisible Energies

A key factor to highlight is the limited academic offerings in Venezuela for training leaders and professionals in renewable energies. Currently, no university in the country offers a degree in Renewable Energy Engineering or formal specialization programs in this field. The Universidad Metropolitana is the only institution that has incorporated a minor in renewable energies within its curriculum, but this remains an isolated exception in a university system still oriented toward traditional models of the oil industry.

This educational gap highlights a profound disconnect between the country’s energy potential and the preparation of its human capital. Without a solid academic foundation —one that integrates science, technology, and sustainability— it will be impossible to build a genuine energy transition. Venezuela needs not only investment and infrastructure, but also education, research, and innovation to train the generation that will lead its energy future.

In the international spaces where I’ve had the opportunity to participate —forums, summits, and meetings on energy and sustainable development, such as the IRENA Youth Forum, the World Future Energy Summit, or the Tellus Summit— I’ve been struck by the innovative energy emerging in other regions of the world: young people leading clean energy startups, universities developing energy projects from waste, and academic ecosystems where applied research drives new technological solutions.

I do not mention this from a Eurocentric perspective or one limited to developed countries. That same creativity also flourishes in challenging contexts — among young people in conflict-affected nations like Ukraine, or in Sub-Saharan and East African countries advancing renewable energy projects as a direct response to the immediate needs of their communities. In many of these cases, innovation is not a privilege but a tool to improve people’s quality of life through access to safe, clean, and affordable energy.

The most concerning issue is not the lack of investment, but the lack of vision. Without an educational system that integrates sustainability as a core principle, the country will continue to view its energy future through the lens of the past.

Between Potential and Planning Capacity

Latin America boasts a privileged location and natural wealth that position it as a key player in the global energy transition. Venezuela, with its abundant sun, wind, and water resources, could become a regional powerhouse in clean energy. However, harnessing this potential requires planning, institutional stability, and political will.

The example of the Gulf countries is illustrative: traditionally dependent on oil, they are now investing part of their fossil revenues to finance their own energy transition. They have understood that the oil market, although still relevant, has an expiration date. Venezuela, on the other hand, has used oil more as a symbol of identity than as a lever for transformation. Yet the real challenge is not to abandon oil overnight, but to transform the way we think about energy, recognizing that development and sustainability are not opposites, but complementary goals.

A Transition That Begins with Awareness

At times, it can be disheartening to feel that the conversation about energy and sustainability happens in isolation. But the energy transition does not begin with a policy — it begins with awareness. A civic awareness built through education, through classrooms, and through the first questions about how we inhabit our environment. Venezuela does not lack resources; it lacks a shared vision of the future. The true transition will not be only technological, but cultural: when we understand that production need not mean depletion, and that prosperity can also mean care, we will have awakened the most powerful energy a country holds — its people.