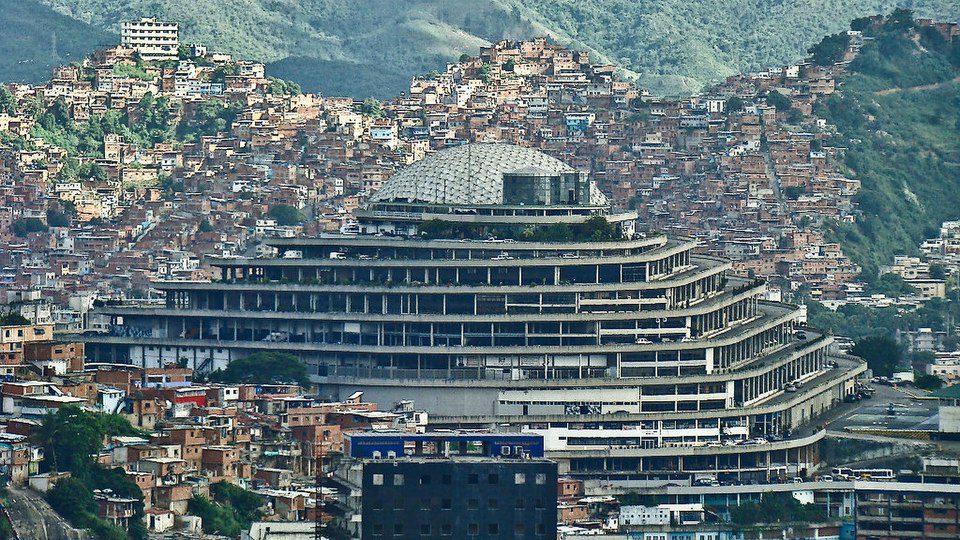

El Helicoide, the main detention center for political prisoners in Venezuela.

Guacamaya, January 30, 2026. Delcy Rodríguez announced a general amnesty law that could benefit hundreds of political prisoners in Venezuela, in an unprecedented move since 1999, shaped by international mediation and a slow, still incomplete process of releases.

The chavista government took a high-impact political step this Friday by announcing a general amnesty for political prisoners in Venezuela—a measure that, if implemented, would mark a break with more than a decade of judicial persecution and politically motivated imprisonment. The announcement was made by Acting President Delcy Rodríguez during a ceremony at the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, closed to the press and first reported exclusively by Spain’s EL PAÍS.

The initiative, which will be sent to the National Assembly, seeks to erase the criminal cases of those who have been released or remain detained for political reasons. Its scope would be far broader than the partial releases that began after Nicolás Maduro was captured by U.S. assault forces on January 3—an episode that opened an unprecedented window of political realignment in the country. The measure would not apply to those convicted of homicide.

So far, releases have proceeded in fits and starts. The government claims more than 600 people have been freed; NGOs and human rights defenders place the figure at just over 300. In most cases, detainees have left prison without fully regaining their freedom: travel bans, restrictions on speaking to the press, and employment limitations remain in place, leaving them in a state of legal and social vulnerability.

Rodríguez framed the amnesty as a gesture to “promote coexistence” and urged that “violence or vengeance” not be imposed, underscoring that the decision had been discussed in advance with Maduro. According to her, the future law will exclude common crimes such as homicide, drug trafficking, and other non-political offenses.

At the same event, the acting president made another symbolic announcement: El Helicoide—an emblem of repression and one of the country’s most feared detention centers—will be transformed into a community hub for social and sports services. She also promised an offensive against corruption within the justice system, one of the main demands of victims and civil society organizations.

Rodríguez’s speech also carried a personal tone. “I come here as president, but also as a lawyer,” she said, recalling her father, a Marxist militant and founder of the movement in which Maduro took his first steps in politics, who died after being tortured in prison. The reference sought to lend moral legitimacy to a measure announced amid national uncertainty.

Key actors stand behind the announcement. Former Spanish prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and Qatar have acted as mediators in contacts with the chavista leadership—a role publicly acknowledged by National Assembly President Jorge Rodríguez when the first releases were announced.

There is no precedent for an amnesty under chavismo since Hugo Chávez came to power. The 2020 pardons granted by Maduro to 110 opposition figures—including members of Juan Guaidó’s team—were an exception and drew criticism for a lack of transparency and information, though it was the only time the government published an official list.

Today, demands go further. Family organizations such as the Committee of Mothers in Defense of the Truth are pushing for an amnesty covering twelve years of repression, starting in February 2014, and encompassing not only prisoners but also exiles, activists, journalists, persecuted military personnel, and political leaders. Their proposal includes the dismissal of charges, independent verification mechanisms, and guarantees of non-repetition.

Days earlier, Rodríguez announced her intention to restore cooperation with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and alleged that some non-governmental organizations had been charging families of detainees. Several organizations issued statements rejecting those claims.

Despite the official announcement, the process remains opaque. There are no public lists of beneficiaries, families do not know the criteria being applied, and in some cases the “concessions” have amounted only to allowing visits for detainees who had been held incommunicado for months.

Members of the diplomatic corps accredited in Venezuela were present at the ceremony, including representatives from several Western and European countries.

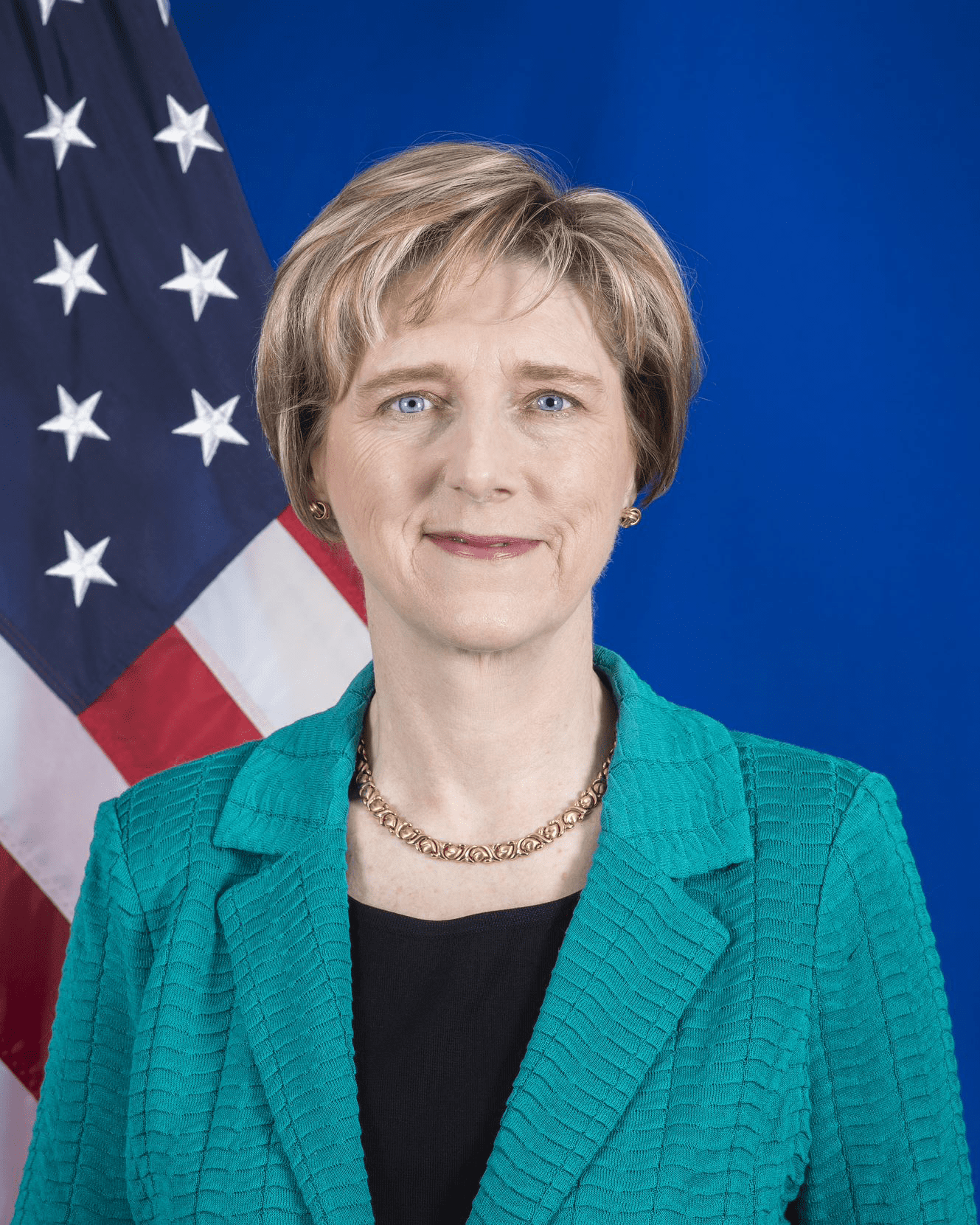

All of this is unfolding as CNN reports that Laura Dogu, the U.S. ambassador appointed to Venezuela, is expected to arrive in Caracas tomorrow, January 31, at the head of a delegation.