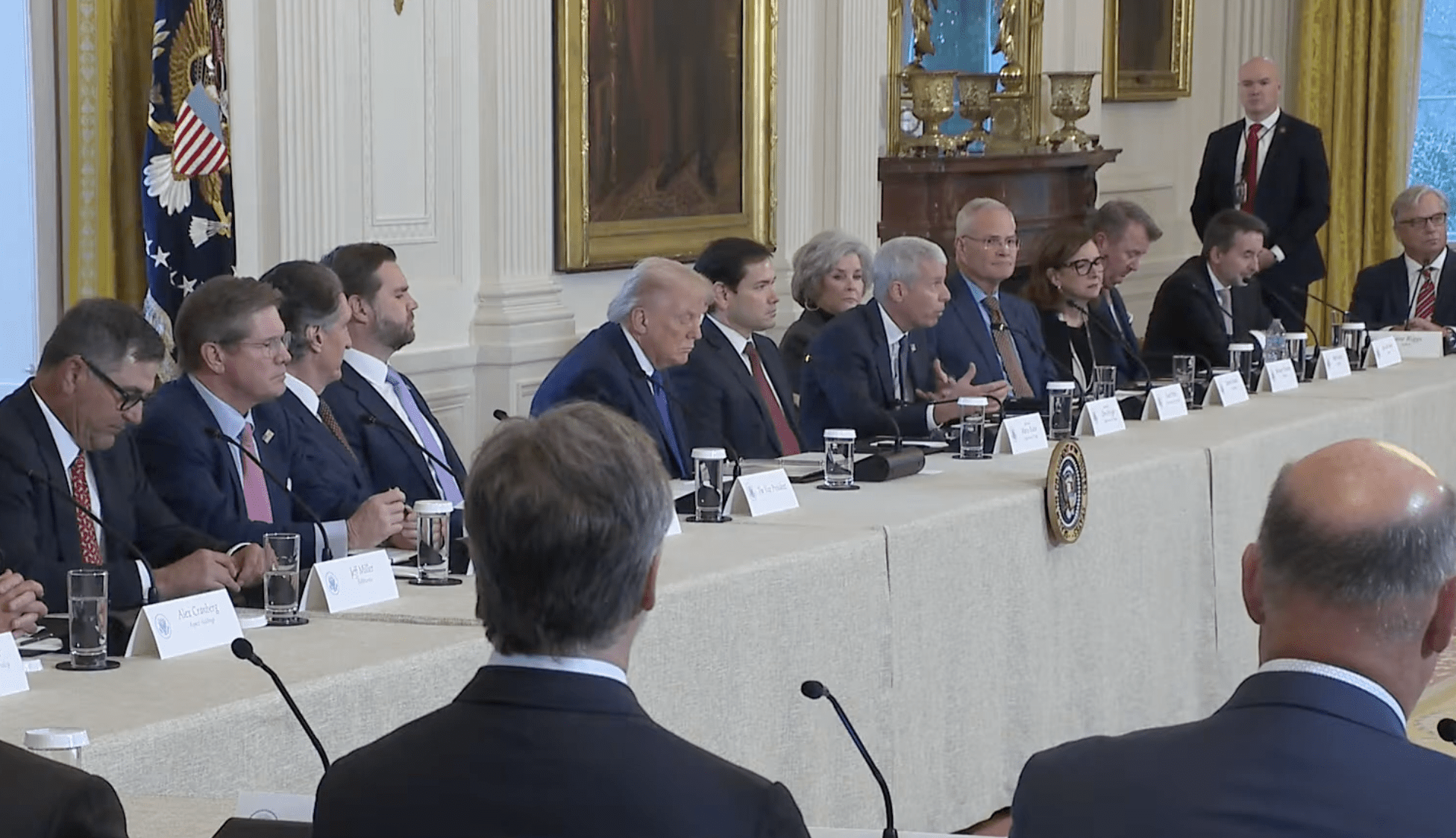

The population of Sweida, located in southwestern Syria near the border with Jordan, is known as Little Venezuela. Photo: social media

Guacamaya, July 21, 2025. In the heart of the Syrian steppe, a hundred kilometers south of Damascus, lies As-Suwayda, a city of black stone and shared memories. The locals call it The Little Venezuela, and it’s not just a nickname: here, every detail seems to hold an echo of our country, every house cherishes a story with a Latin accent.

In the cafés of the souk, you can still hear Simón Díaz’s songs intertwined with those of Fairuz, and family photos hang on the walls where Venezuelan grandchildren pose next to their Druze grandparents in some Venezuelan city.

“Venezuela remains in our hearts,” repeat the families marked by migration to Venezuela and return, with a nostalgia that seems even stronger now, amid the gunfire.

Everyone here has some cousin, nephew, grandchild, or aunt in Maracay, Valencia, Punto Fijo, Margarita, Caracas, or Ciudad Bolívar. Since the 1950s, the Druze of Suwayda emigrated to Venezuelan lands, seeking a future in gold mines, coffee plantations, and later, in oil wells. Some returned with children and grandchildren who spoke Spanish. Others stayed behind, sending money, letters, clothes, and, above all, a piece of Venezuela that ended up being ingrained in the identity of this Syrian corner.

From then on, the city was not only called La Negra due to its volcanic basalt but also The Little Venezuela.

In 2009, when the then Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez forged ties with Bashar al-Assad’s government, the relationship became official. The Venezuelan leader visited Suwayda and laid the first stone of the Venezuelan club in the city. He gave a speech at the local football stadium: “I feel that Damascus is my home, and Suwayda is my house,” he said in his address.

Many citizens were forced to migrate to Venezuela starting in 2011 due to the Syrian Civil War and the ongoing confrontations. Years later, others would return as Venezuela’s economic situation worsened and the conflict intensified.

In the Druze community, there were also supporters and opponents of Bashar al-Assad. Many in this town protested against him, others supported him, and some fought against the ISIS jihadist militias.

Hikmat al Hijri: From the Caribbean to the Hauran Highlands, the Druze Leader with Venezuelan Roots

Amid the storm shaking Syria and its Druze minority, one name resonates strongly: Hikmat al Hijri, the sheikh who has led this community spiritually since 2012 and who holds a surprising connection to Latin America.

Al Hijri was born on June 9, 1965, in Venezuela, where his father, Sheikh Salman Ahmad al Hijri, was living and working at the time. He spent his childhood in Caribbean lands before returning as a teenager with his family to Syria, where he completed his basic education and then earned a law degree from the University of Damascus between 1985 and 1990.

In 1993, he returned to Venezuela for a few years to work and maintain his connection with his birthplace. However, in 1998 he returned permanently to Syria, settling in Qanawat, a town near Suweida considered the spiritual center of the Druze.

Raised in a traditional religious environment, Al Hijri rose through the spiritual hierarchy of his community until 2012, when he succeeded his brother Ahmed, who died in a suspicious accident. Since then, he has been the voice of the Syrian Druze in an increasingly complex context.

The sheikh himself still holds a Venezuelan passport, as did his brother, and is part of that large diaspora of Venezuelans of Druze descent—a community that, before the recent exodus, numbered between 300,000 and 500,000 members in the South American country.

In his early years at the head of the community, Hikmat al Hijri was a close ally of then-President Bashar al Assad. In 2012, he even declared: “Bashar, you are the hope of the nation, of pan-Arabism, and of the Arabs,” and urged the Druze to take up arms in defense of the regime during the early phases of the civil war.

However, his relationship with power began to fray after a phone incident with an army general in 2021, which he described as a personal and communal humiliation. That dispute sparked protests in Suweida, which were brutally suppressed by the government.

After Assad’s fall and the arrival of an Islamist government led by Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), the sheikh cautiously welcomed the change. But subsequent clashes between the new authorities and the Druze community also broke that relationship, leaving Al Hijri as a critic of both the old and the new regimes.

In recent weeks, as Suweida has once again become the scene of bloody fighting, Al Hijri has remained defiant: he has denied having made a pact with Damascus to pacify the province and has called for the resistance to continue “until the complete liberation of our land from the gangs,” referring to both government forces and rival militias.

Today, his figure is one of the most influential in the country, capable of negotiating with presidents and challenging armies, while carrying not only the weight of his community but also the memory of his childhood in Venezuela and the bond of thousands of Druze with the Caribbean. From Qanawat, at the foot of the Hauran, this spiritual leader embodies, perhaps, the most visible incarnation of that long history that unites the Middle East and Latin America.

But now, in the scorching summer of 2025, the streets that once filled with red flags and maracucho gaitas are now tinged with fear. Since July 13, clashes between Druze and Bedouin clans have turned the city into a battlefield. In just a week, nearly 260 people have been killed, and over 120,000 displaced. The Syrian Arab Red Crescent evacuates Bedouin families in buses, while the Druze contemplate whether to stay and defend their land or seek refuge in the mountains.

The black stone houses that once opened to celebrate weddings with hallacas and baklava now remain silent behind shattered windows. Venezuelan flags hanging from balconies flutter at half-mast, weathered by the war. Israel, invoking the defense of its “Druze brothers,” bombed the Syrian Ministry of Defense buildings in Damascus and positions in Suwayda, adding fire to the already fragile truce.

Young people who once dreamed of traveling to Caracas or Valencia to meet their cousins and uncles now dream of surviving the night. However, images of separation return as some watch families leaving for Daraa on escorted buses.

A Conflict That Exceeds Borders

What is happening in Suwayda is not just a local confrontation. In geopolitical terms, this small city has become a friction point on the Middle Eastern chessboard. The Druze —a religious minority historically allied with the Assad regime but protective of its autonomy— now clash with the Bedouins in a context of economic crisis, the weakening of the Syrian state, and the growing pressure from external actors.

Israel has intervened directly with airstrikes, both to project its power and to present itself as a protector of Druze communities in Syria and in its own territory. For Damascus, maintaining control over Suwayda is key to demonstrating that the country is not fracturing beyond what has already been lost in the war. And for actors like Iran and Hezbollah, southern Syria —where Suwayda lies— is a strategic zone for their influence and presence near Israel.

At the same time, social tensions, poverty, and the lack of services have ignited community tensions that had long been contained by repression or political alliances. Now, that pressure cooker has exploded, while the international community, exhausted by more than a decade of war in Syria, barely responds with emergency evacuations and formal statements.

The Urgency of an Active Diplomacy

For Venezuelans, looking at Suwayda is not just a sentimental gesture: it also reminds us that we are deeply intertwined with stories of migration, solidarity, and shared identity. Thousands of Syrian-Venezuelans still live there, trapped between bullets, bombings, and an uncertain future. In their homes, documents, and accents, there are pieces of Venezuela that today suffer under the shadows of war.

Venezuela is no stranger to the Middle East. Since the founding of OPEC in Baghdad in 1960, Venezuela has shared with Syria and other countries in the region a vision of South-South cooperation, resource defense, and solidarity with the causes of the Arab peoples. This heritage is not just oil-based: it is also in the migrant communities, in the family stories, and in the shared values of hospitality and resistance.

Today, in a context where Venezuela is confronted with the wall of the limitations of its internal crisis, it is difficult to expect a diplomacy worthy of that history and the valuable ties that connect us to the essence of what we are as a country. It is no secret that the conflict has affected our voice and presence in the world, but that should not prevent a broader public debate on this issue, as there are Venezuelan lives at risk and without protection.

Since 2006, Venezuela has been an observer state in the Arab League, a key diplomatic space where the main concerns and strategies of the Arab world converge. Although its role is limited, this status allows for direct interlocution with governments in the region and a formal channel to express solidarity, propose humanitarian initiatives, and support political solutions. In the case of the Suwayda conflict, Caracas could use its observer status to advocate for the protection of the Druze-Venezuelan communities and for stability in Syria, demonstrating that its participation in the League is not merely symbolic but substantive. Looking toward the future, this should be an important issue in any foreign policy agenda for Venezuela in the coming decades.

The families of Suwayda are not just “the Syrians” or “the Druze”: they are the uncles, grandparents, and cousins of those in Guárico, Maracaibo, Puerto La Cruz, Valencia, El Tigre, or Caracas. Their fate is also ours, and their resilience is a reflection of ours. In times of war, remembering that we are part of that history compels us to not forget the humanitarian, diplomatic, and moral responsibility we have toward those who, in a corner of the desert, still wave a tricolor flag with affection.

Seeing what has happened to Venezuelan migrants in the United States—kidnapped and sent to El Salvador—and this situation in Syria, which has lasted for years, it becomes necessary for all actors in the country to engage in a serious discussion to protect Venezuelan communities abroad, now and in the future.