Guacamaya, September 4, 2025. On July 25, 2025, the Treasury department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned what it called “the Cartel de los Soles (a.k.a. Cartel of the Suns)” as a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist Organization.” By August 7, the State and Justice departments increased the bounty on its alleged leader, Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, from $25 million to $50 million.

On September 2, the U.S. military destroyed a speedboat in a targeted strike in international waters, alleging it was carrying drugs from Venezuela with 11 members of the Tren de Aragua gang. Despite questions over its legality and usefulness, the administration defended that it was an act against a “narco-terrorist” group.

A first reward of $10 million had been offered in 2020, alongside an extravagant accusation against the supposed Cartel de los Soles. The argument, then and now, is that Maduro is not a head of state, but rather the leader of a criminal organisation. What is more, he is a “narco-terrorist” for trying to “flood the United States with cocaine.” To this end, in 2020, Maduro would have instrumentalised Colombian guerrillas. And in the second Trump administration, they have been substituted by the Tren de Aragua.

In this investigative piece, we find that the allegations made by State and Justice, both in 2020 and in 2025, are baseless and false. Some cocaine smuggling routes transit through Venezuela, often with the permission or help of corrupt government officials and members of the armed forces. However, there is no evidence to indicate that Maduro heads a drug trafficking organisation, or that he is purposefully flooding the United States.

Instead, what we find in Venezuela is a regional phenomenon, of highly profitable illegal economies taking advantage of poverty and weak institutions—the latter two factors are particularly severe in this South American country. To this day, Venezuela remains a minor corridor for the cocaine trade when compared to other vectors like the Eastern Pacific, the Mexico land border, and the Brazilian Amazon.

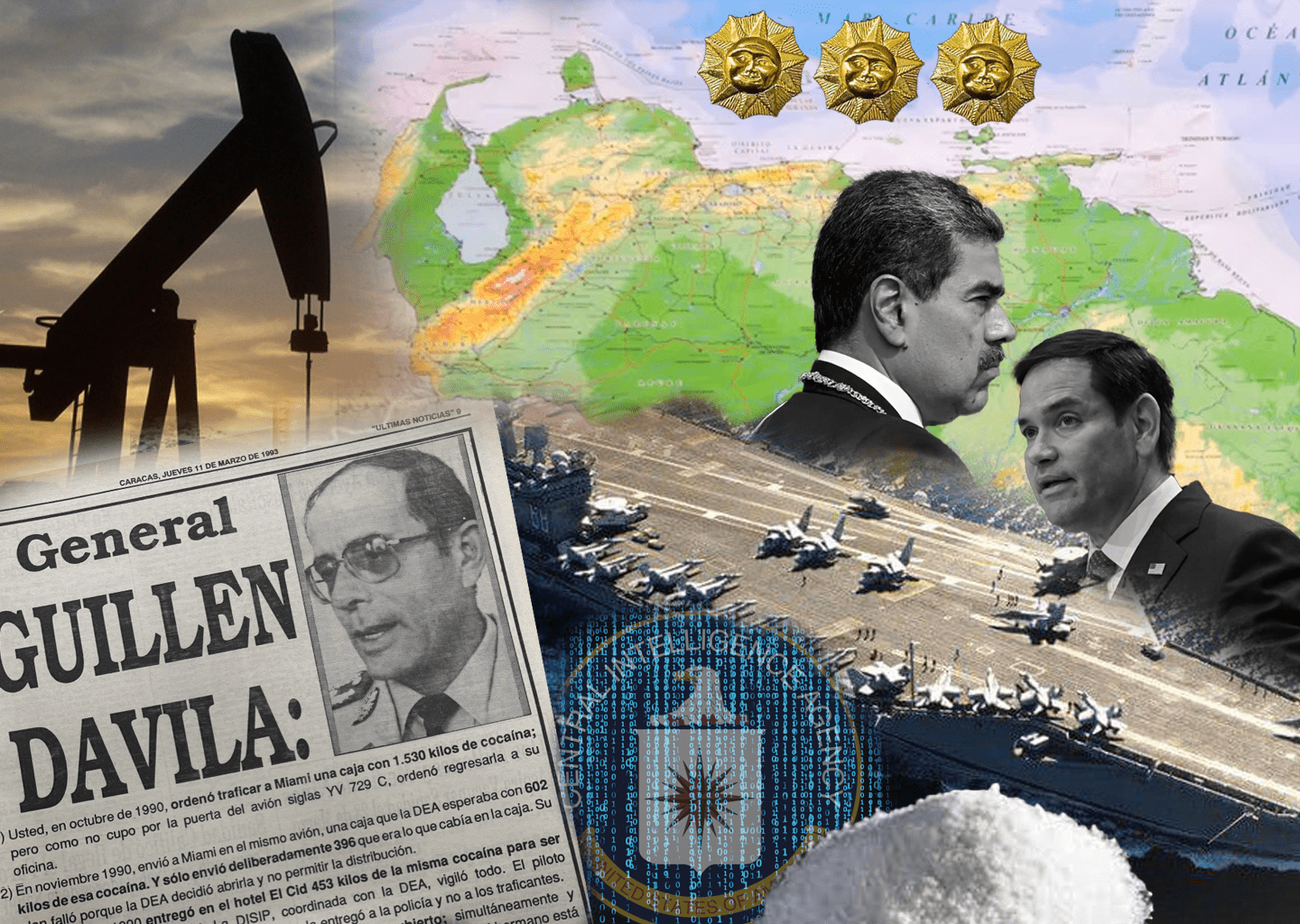

A “Cartel of the Sun”

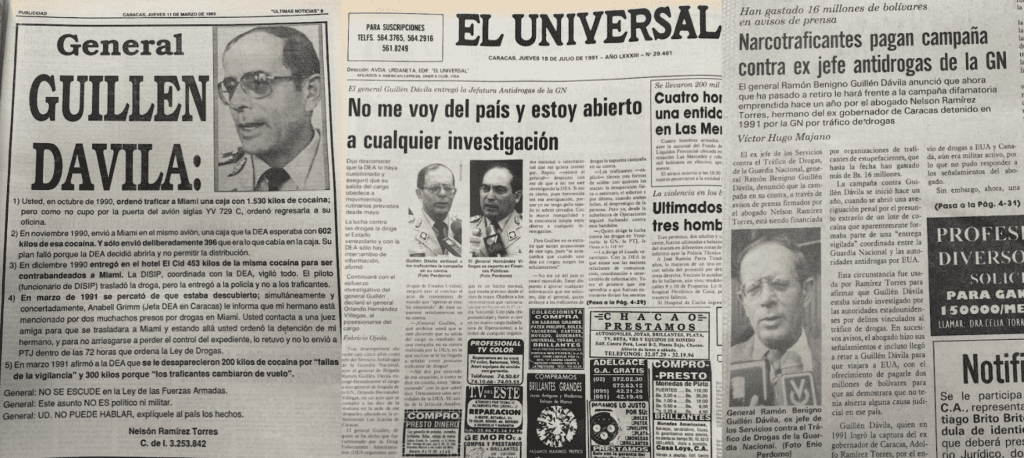

In Venezuela, the idea of the Cartel de los Soles appeared in 1993—well before Chávez’s presidency—with the investigations and arrests of two National Guard generals, as they were accused of trafficking cocaine into the United States. They were Ramón Guillén Dávila, the head of the anti-drug office, and his successor, Orlando Hernández Villegas.

The name Cartel del Sol (Cartel of the Sun) arose from the insignias of brigadier generals; Guillén Dávila and Hernández Villegas both wore a sun-shaped badge to show their rank. Rather than being the name of a cohesive organization, like the Medellin or the Sinaloa cartels, it became a journalistic label for corruption within the military, where officers would take bribes from criminal groups to enable the smuggling of narcotics and other goods, like illegally mined gold.

This first case became especially notorious beyond Venezuela. The Administrator of the DEA at the time, Robert C. Bronner, accused the CIA of working with Guillén Dávila to send at least a ton of cocaine into the United States. While controlled smuggling operations to gather intelligence are not uncommon, Bronner alleged he was never informed.

In November 1993, 60 Minutes dedicated an episode to the issue, called “The CIA’s Cocaine.” The interviews, including of Bronner and Guillén Dávila, seemed to indicate that no useful intelligence was obtained from this operation, while the ton of cocaine reached American streets, nonetheless.

The case was a true scandal. Press coverage spoke of the “worst breakdown” in communications between the two agencies, and that the “ultimate beneficiary” was Pablo Escobar’s Cartel de Medellín, as we can see in Los Angeles Times, Tampa Bay Times, CBS, and Bogotá’s El Tiempo.

In Venezuela, the investigations against Guillén Dávila and Hernández Villegas were eventually dropped during the government of Carlos Andrés Pérez. No one was charged on the U.S. side, although two CIA officers resigned under pressure.

Later, during the rule of Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) and his successor, Nicolás Maduro (2013-present), the idea of the Cartel de los Soles took on a new meaning. In the period of extreme polarisation since their rise to power, there started to arise accusations against both presidents of not just enabling, but heading drug trafficking organisations themselves. While there is no conclusive evidence to back this claim, it has become popular among their opponents.

But how much of this is true? To what extent is Venezuela a key player in the supply chain for cocaine or other drugs? Is there a clear vector between this country and the U.S.? How are civilian and military officials involved? How much is part of a regional pattern, and how much is unique to Venezuela?

The Cocaine Map

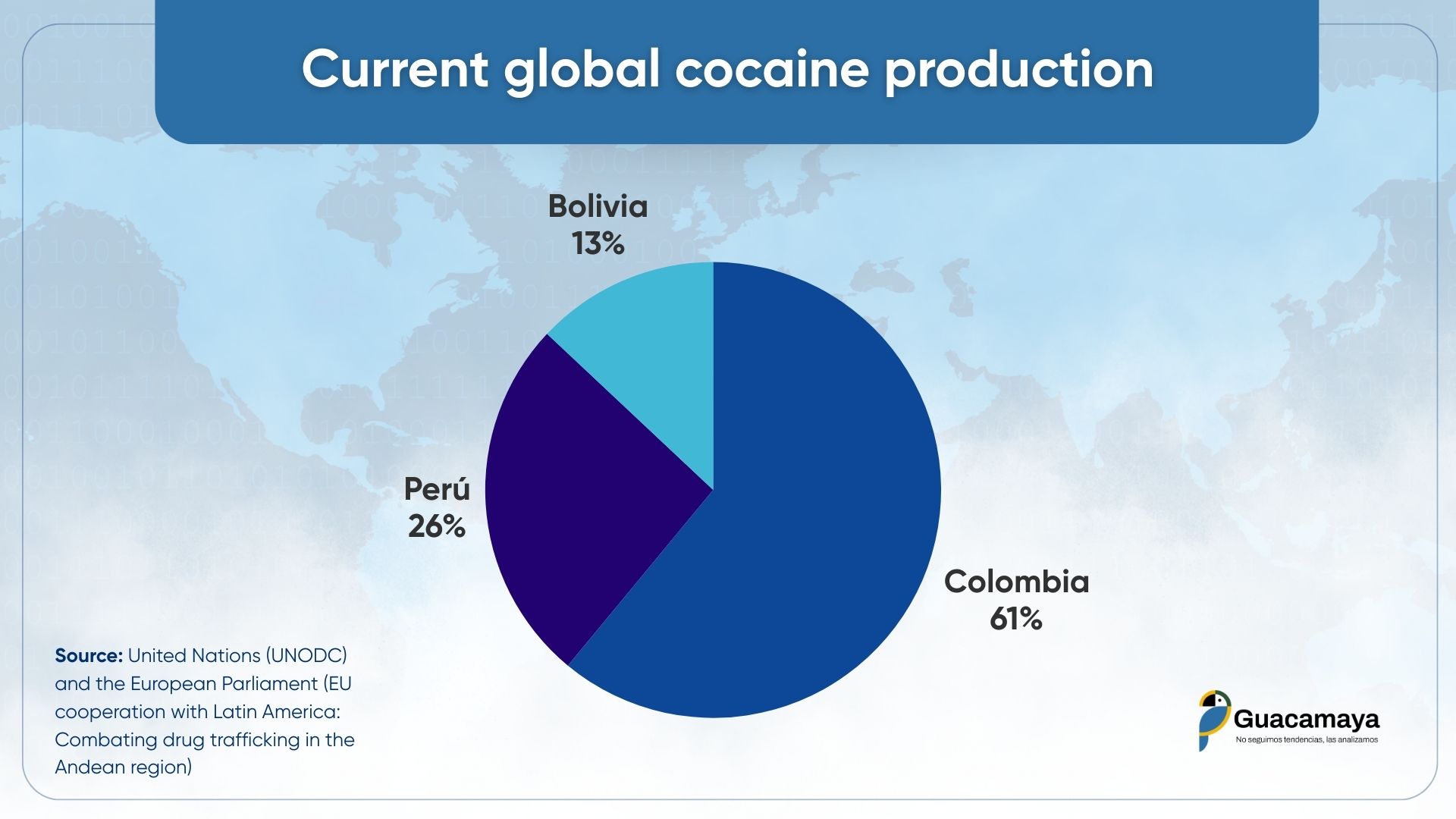

According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, virtually all cocaine produced globally is sourced from Colombia (61%), Peru (26%), and Bolivia (13%). The three Andean countries can count on an ideal humid, tropical climate at specific altitudes that is required to grow the coca plant.

Some production has been taking place in adjacent areas within nearby countries like Chile, Ecuador, and Venezuela, though it is insignificant at the global scale. In the last country, armed forces have on some occasions found and destroyed labs in the state of Zulia, within the remote region of the Catatumbo, which stretches across both sides of the border with Colombia, the country that remains the world’s top producer.

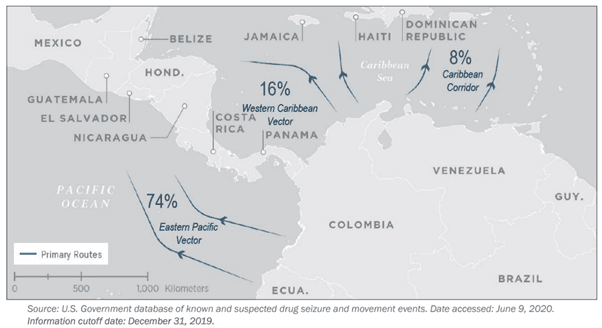

The main export routes connect the three Andean countries with their largest markets: North America and Western Europe. In the early boom of the 1970s and 1980s, the Caribbean served as the most direct route between Colombian producers and Miami. Since then, however, smugglers have transitioned towards alternative routes as surveillance increased in the region and markets evolved.

Europe has become the largest consumer globally, growing by an extraordinary 416% over the last decade, turning ports in Ecuador and Brazil, such as Guayaquil, Manaus, and Belém, into key hubs. Simultaneously, U.S.-bound routes have shifted towards the Pacific Ocean and the Mexico land border, the latter benefiting from free trade agreements starting in 1992.

In this context, Venezuela does not appear to be among the top producers or exporters. It does play a role, providing a minor corridor given its geographical location: it is squeezed between the largest producer and the longest Caribbean coastline. Its porous, remote border areas with Colombia and Brazil allow for irregular groups to cross, while they take advantage of weak institutions to corrupt local officials.

The DEA estimated that in 2019, 90% of the U.S.-bound cocaine trade transited through the Eastern Pacific (74%) and Western Caribbean (16%) vectors, traversing through and around Central America and Mexico. The Eastern Caribbean, where we find Venezuela’s coastline, saw only 8%. Earlier reports show similar proportions for 2015, 2016, and 2017.

It must be noted that the National Drug Threat Assessments do not offer a concrete estimate of the share of the narcotics trade that passes through Venezuela specifically, contrary to a baseless claim that “almost 24% of the world’s cocaine production transits through” this country.

A report by the Washington Office for Latin America was able to view data from the U.S. Consolidated Counterdrug Database (CCDB), which can give us a better understanding of the scale of traffic.

For 2018, it was estimated that 210 metric tons of cocaine moved through Venezuela. This figure, while it is high, is marginal when compared to other routes. 2,372 tons were trafficked out of Colombia directly. Since 2013, when Maduro rose to power, the two routes have maintained a ratio of 9:1. Simultaneously, that same year, more than 1,400 metric tons transited through Guatemala—a much smaller country—while the Mexican land corridor is estimated to have moved 2,000 metric tons by the State Department.

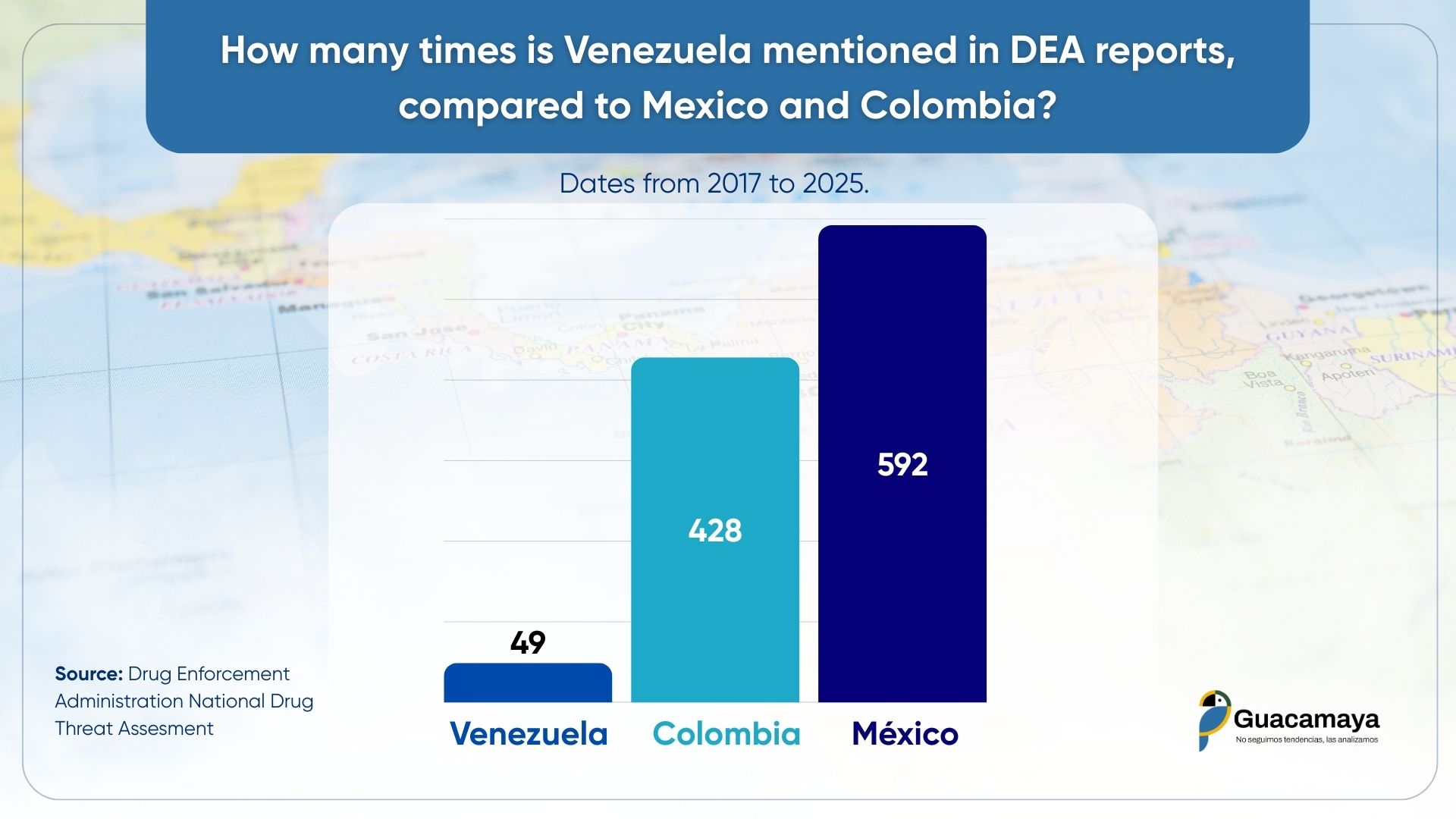

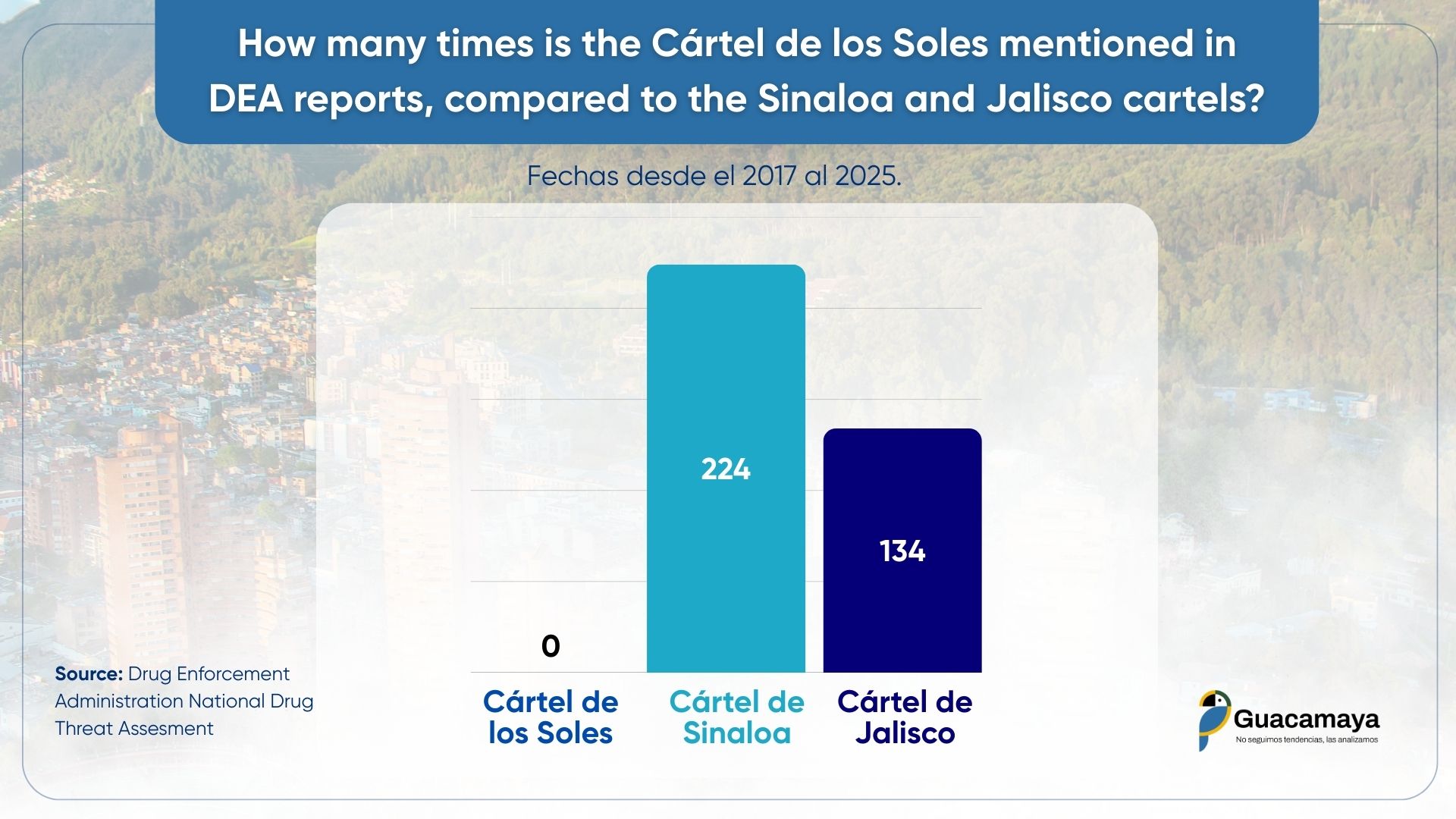

The two most recent National Drug Threat Assessments by the DEA (2024 and 2025) are explicit: the groups that concentrate the most control over drug trafficking towards the U.S. are the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). Their sprawling presence stretches over 40 to 50 countries, with strategic ports and global financial networks. None of their evaluations mentions the Cartel de los Soles—or a “Cartel of the Suns,” for that matter—nor does it point to Venezuela as a structural threat or a central point in the illicit drugs trade.

Regarding trafficking towards Europe, investigations have pointed to the Pacific and the Atlantic, using large port infrastructure and escaping traditional, heavily surveilled routes. In 2023, the mega-port of Antwerp saw the seizure of 121 tons of cocaine, the majority of which came via Colombia and Ecuador. In a 2022 report, Europol found that the main points of departure are Brazil, Ecuador, and Colombia, while other countries like Chile, Panama, Peru or Venezuela came far behind. The Financial Times described the Amazon rainforest as a “superhighway” for cocaine moving towards Europe, where Brazilian mafias like Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) and the Comando Vermelho battle over routes with Mexican cartels.

A structural problem in the region

The illicit drugs trade in Latin America is, before anything else, a structural phenomenon. The region continues to be one of the most unequal in the world, with high levels of poverty and social exclusion, according to the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). We must also consider vast, remote territories out of the reach of the state; porous borders; and a sustained demand first in the U.S., and later also in Europe and other industrialised economies.

Geography also favours this phenomenon. Extensive rainforests and mountain ranges, along with broad coastlines, facilitate clandestine operations. The Andean-Amazonic region is not only ideal for the cultivation of coca, but also for hiding labs and export routes.

The windfalls offered by cocaine production, and even more so by trafficking, are monstrous. InsightCrime estimates that just the 600-ton increase in Colombia’s output from 2018 to 2022 is “worth $1.2 billion at source prices, and at least $20 billion on international wholesale markets.”

Together, all these conditions created a perfect breeding ground for highly profitable, illicit economies to flourish. Cocaine is just one of them, alongside illegal mining, human trafficking, and other activities.

Venezuelan government officials and the drug trade: A cartelised network or isolated corruption?

In our investigation, we found that the Cartel de los Soles was born in 1993 as a journalistic label attached to a group of generals who were working alongside the CIA. There was no evidence yet of a consolidated criminal structure within the Venezuelan state or the armed forces.

But the Cartel of the Soles idea we know today, that is being pushed by the State Department is different: it claims that Venezuela’s top government officials are at the head of a “narco-terrorist” organisation, which are “using cocaine to flood the United States.”

This accusation was first formally made on March 26, 2020, by the U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr, charging President Nicolás Maduro, Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino López, and the then economy vice president Tareck El Aissami and National Constituent Assembly head Diosdado Cabello, alongside other Venezuelan officials and two Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) leaders. However, neither that accusation nor the reiterated claims in 2025 have been presented with any evidence; all we have are empty claims.

Recent DEA National Drug Threat Assessments, from 2017 to 2025, reinforce the vision that Venezuela is still a minor player in the cocaine trade, and insignificant when considering other narcotics. The country is named 49 times, against 428 mentions of Colombia and 705 of Mexico. The “Cartel de los Soles” is never mentioned, which undermines the Justice Department’s allegations. Meanwhile, the Sinaloa Cartel is named 224 times. The agency concurs with UN and European Parliament findings that Venezuela is not a major producer, while its role in global routes is secondary, well behind the Eastern Pacific corridor.

What cannot be questioned is that drug trafficking exists in Venezuela, and that there have been cases of government and military officials colluding with criminals. This is nonetheless a pattern that is seen across Latin America, exacerbated in large part by the recent period of economic collapse, where nominal GDP fell from a peak of $372 billion in 2013 to a trough of $43 billion in 2020, as per IMF estimates.

High-level officials being bought off and co-opted by drug trafficking organisations is not unique to Venezuela. In Mexico, we have witnessed the cases of former Secretary of Public Security Genaro García Luna, a leading figure in the “war on drugs” from 2006 to 2012, who was later tried and convicted for working in cahoots with the Sinaloa Cartel. General Salvador Cienfuegos, who was Secretary of National Defence from 2012 to 2018, was arrested and indicted for working with the Beltrán Leyva Cartel. Charges were dropped in 2020 “without prejudice,” meaning it could be reopened, as the federal judge overseeing the case argues it is still “solid.”

In Venezuela, the only high-level government official that has been convicted in the U.S. for drug trafficking is Hugo “El Pollo” Carvajal, who headed the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM) from 2004 to 2011 under Hugo Chávez, and then briefly from April 2013 to January 2014.

Carvajal was accused of enabling and protecting the FARC within Venezuelan territory, allowing them to establish themselves in uninhabited parts of the state of Apure, and to smuggle cocaine through the country. He was also alleged to have received payments from Wilber “Jabón” Varela, a Colombian drug lord from the Cartel del Norte del Valle. After Varela was killed by his own men in 2008, Carvajal and other government officials would have received payments from Mexican cartels.

In other cases, such as that against Carlos Orense Azócar, a convicted narcotics trafficker, arrangements included bribes to civilian and military government officials to allow the transit of drugs through Venezuela. Still, no proof exists to back the idea that there is an organised, hierarchical cartel led by Maduro himself, or that he is pushing cocaine into the U.S. Instead, we find a regional phenomenon of the illegal trade penetrating weak institutions.

Investigations by InsightCrime demonstrate that the concept of the Cartel de los Soles is useful as a narrative construct to describe corruption in the military, but without there being proof of criminal coordination at a large scale: “It presents a simplified, distorted narrative of drug trafficking in Venezuela—a Hollywood version of the Cartel de los Soles.” The closest thing to evidence is accusations by politicians in the U.S., without any support from DEA, UN or other official reports.

A still more outlandish claim is that Maduro would now be flooding the U.S. with drugs and weapons by using the Tren de Aragua. Originally a Venezuelan gang, it spread across the Americas in the midst of the country’s mass emigration phenomenon. According to the Atlantic Council’s Geoff Ramsey, “Tren de Aragua has become more like a brand that any group of carjackers from Miami down to Argentina can invoke to further their criminal activity, but there’s really no clear sense of hierarchy.”

Evidence of the accusation is non-existent. The 2025 DEA report does dedicate a section to the group, for the first time, given that it was designated as a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” by the Trump administration earlier this year. Still, the NDTA argues the Tren de Aragua “conducts small-scale drug trafficking activities such as the distribution of tusi. In some areas of the United States, TdA members work for larger criminal organizations, conducting murder-for-hire and working as drug couriers, stash house guards, and street level drug distributors.” There is no mention of the gang carrying out large-scale narcotics operations, smuggling drugs into the U.S., or working for Maduro.

Meanwhile, the U.S. intelligence community—including the CIA and the National Security Agency (NSA)—has denied that Maduro directs the Tren de Aragua. The accusation could have more to do with the Trump administration’s immigration agenda, as it invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to push for mass deportations, than with a real threat.

Colombian guerrillas: The true protagonists

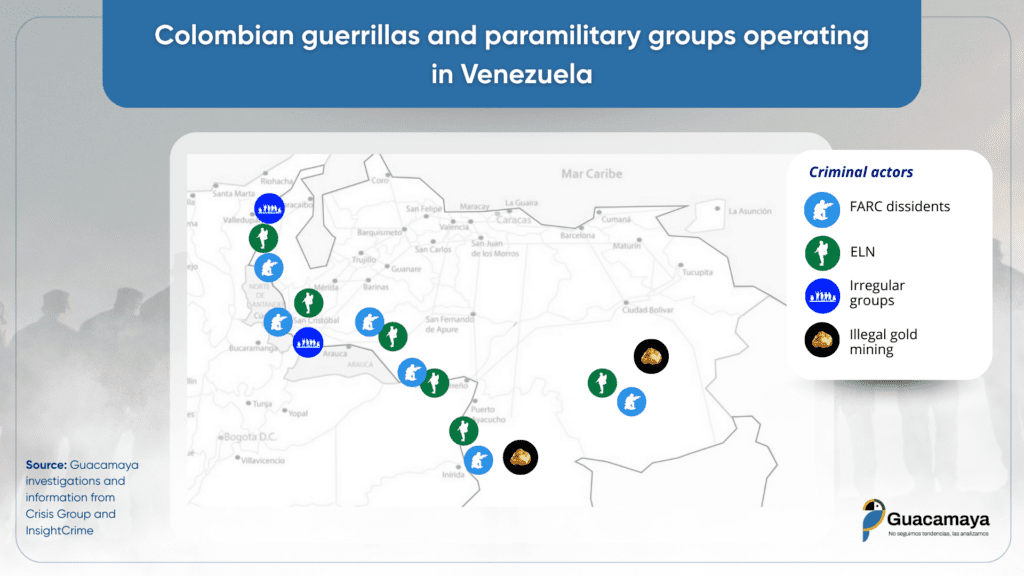

It has been documented extensively that Colombian rebel groups have been operating within Venezuela’s territory, mainly along the western and southern border states of Zulia, Táchira, Apure, Bolívar and Amazonas. As well as narcotics, from 2010 they have been drawn in by a gold rush. These have included right-wing paramilitary groups, the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN), and the FARC, as well as its breakaway groups since 2017, like the one known as “Segunda Marquetalia.”

These groups have become central actors in Venezuela’s drug trade, taking advantage of the country’s institutional weakness. They are also reported to be taking part in other illegal activities, particularly gold mining, extortion, and human trafficking.

Their relationship with the state has been volatile. The Maduro government has at times allowed them to take up space in remote areas, especially as it lost its capacity to control the entire national territory, given the sudden drop in resources in the period between 2014 and 2020. They have also clashed, however. The most famous case was a battle between FARC dissidents and the Venezuelan army in March of 2021, around the border town of La Victoria in Apure.

Carúpano: Where euros swept ashore

To get a better grasp of how drug trafficking works in Venezuela, we move East to the state of Sucre, where drug trafficking left deep footprints. It is one of the poorest regions in the country, occupied by tropical forests and mountains. It includes the Peninsula of Paria, which almost reaches the island of Trinidad, with just 10 km (6.2 miles) in between.

At the start of the 1990s, in Carúpano, Sucre, the expression “pegó la vuelta” was commonly heard when a smuggler was able to cross barriers and introduce drugs on the route towards Europe. As a consequence, euros started circulating in the city. “You could see euros like they were bolívares,” says José, a local fisherman.

Since 2020, police and army units have been cracking down on the illicit drugs trade in Sucre. In Macuro, the closest town to Trinidad and Tobago, the authorities seized 790 kilos of cocaine in a single operation in February 2025. The euro and other foreign currencies have become much rarer, although they can still be spotted as some trafficking continues.

While criminal organisations find alternative routes, the movement of narcotics created interesting phenomena, and as locals explain them to us, we can have a glimpse of how the drug trade really operates in Venezuela.

José explains that the actions by security forces against local drug smugglers have been felt on the local economy. Standing on the shore, he confirms without hesitation: “It is no secret that these coasts were being used by drug trafficking, but with the continued blows that they’ve been receiving, that has been falling apart.”

A phenomenon seen across Latin America is how these illicit activities take over control of local economies, generating new incentives for their functioning. José says that traffickers usually operate by bribing government officials who otherwise earn very low salaries.

“It has been a few years since I last saw a euro. Sometimes I go weeks without seeing a dollar, when it used to be normal to receive them every week,” he says. This economy, though illicit, he explains, generated indirect jobs: “Those people put money into construction and other businesses to launder money. When that fell apart, many people were left unemployed.”

A local odontologist has also been a witness to the decline in the use of the euro. In the past, he says, “patients coming from San Juan de Unare, San Juan de las Gandolas, and El Morro de Puerto Santo, came in and paid with euros or dollars, no questions asked.” The picture has changed now, however. “Now, when they come it’s because they really have a health problem. You see them coming in on the 15th, when they get the government bonus.”

In Venezuela, public sector employees, pensioners, and some private sector workers receive very low base incomes, as the minimum wage is just 130 bolívares, below one dollar. They thus depend mostly on the payment of bonuses by the government, which can add up to just over $100.

A gym trainer points out that it was usual to see customers “arrive in luxurious cars, with good cell phones and gold jewellery. They’d pay with 50- or 100-euro notes.” The latter are rare to see even in European streets. “Now, everything is in bolívares, though sometimes in dollars,” which is more commonly seen across Venezuela’s semi-dollarised economy. “The money that’s being moved now is more normal, more from real work, not like before with dirty money.” The story told by locals is clear: the rise and fall of the drug trade altered the social and economic fabric of the area.

False accusations have consequences

There is a long list of faults committed by Venezuelan government officials. Specifically regarding drug trafficking and corruption, there have been cases that have even led to convictions. And it is not necessary to produce false narratives to criticise Maduro. There are very real problems with him, like his management of the economy or his treatment of political opponents. Instead, the State Department is leading a movement to turn Venezuela’s plight into a mere law enforcement issue.

By pushing serious accusations without any substantial evidence, the U.S. government is hurting its own credibility. Key regional partners, like Mexico and Colombia, are already dismissing the allegations. Will this undermine real, necessary cooperation to fight drug trafficking?

We know where false political narratives can lead us. In 2003, the U.S. government fabricated a claim where it said that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, which was then used to invade the country. Thousands of innocent people died, and Iraq was irreparably damaged.

Already, we can see the first victims. The story of the Tren de Aragua gang is being overblown and instrumentalised to suspend the rights of Venezuelan and other Latin American migrants, most of whom are ordinary, hard-working people.

We need to ask ourselves a very important question. Why is this false narrative being promoted so strongly? And why now? This will be the subject of a second investigative piece, to be published in the coming days.