This piece is the second in a series of investigations on the ‘Cartel de los Soles’ political narrative.

Guacamaya, September 8, 2025. Last week, the U.S. military struck an alleged drug trafficking boat in international waters, with the backdrop of a Navy deployment in the Caribbean around Venezuela’s coasts. Officially, they are working to counter drug trafficking by the Cartel de los Soles or the Tren de Aragua, which would be headed by no other than Nicolás Maduro.

In a recent Guacamaya investigation, we explained why the accusations about the Cartel de los Soles are not rooted in reality, while they are part of a narrative to push certain political goals. But why are these allegations taking root? Who is interested in promoting them? And why is it happening now?

Initially, for a few cynical opposition figures in Venezuela, promoting the idea of the Cartel de los Soles was straightforward. Anything was fair if it could help in bringing down first Hugo Chávez, and later Nicolás Maduro. If the solution is a U.S. military intervention, and the way to get it is to claim that Venezuela is a ‘narco-state,’ then so be it.

In the United States and other countries in the Americas, however, the narrative was used and abused for economic or domestic political purposes, which had nothing to do with liberating Venezuelans from a tyrant. For years, it has served electoral goals in South Florida and big oil interests. And more recently, it has gotten caught up with President Donald Trump’s agendas of mass deportations and of using the military to fight drug trafficking.

Why the Navy deployment is about regime change, not drug trafficking

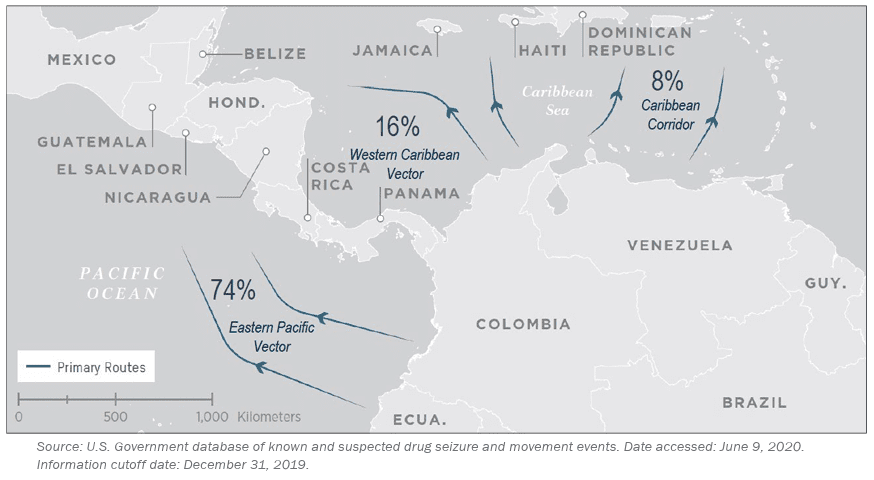

There are no recent, shocking drug-related scandals involving Venezuela. In the United States, the fentanyl crisis would be the most pressing issue, as in 2023 70% of overdose-related deaths in the country were due to this drug. We could also speak of an opioid epidemic, or of intensifying cartel violence in Mexico as the next priorities. But Venezuela is not part of any of these issues, right?

Cocaine seizures by the DEA have also increased progressively at the southeastern border—meaning with Mexico—by 37.6% if we consider the 2022-2025 period. Meanwhile, in the ‘Coastal/Interior’ theatre, which includes the littoral and metropoles like Chicago, they fell by 54.2%. Again, it seems strange that Washington, DC would want to focus on a Caribbean operation. One would think the authorities would want to focus on the Mexico land border and the Pacific Ocean, where we not only see the majority of cocaine smuggling, but also the main routes for fentanyl, methamphetamine and other narcotics.

This gets worse. The recent U.S. Navy deployment in the Caribbean does not have the capacity to efficiently combat drug trafficking, but instead ‘is entirely a matter of political signalling,’ argues Mark Cancian, senior advisor on defence and security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and retired colonel from the U.S. Marine Corps.

‘The ships have no law enforcement authority, unlike the Coast Guard, which normally conducts counterdrug operations,’ explains Cancian. ‘Further, they can’t do anything ashore without the agreement of the host country. The exercise has received a lot of attention, which was the point.’

A former high-level Pentagon official told Guacamaya that the Navy deployment is not an effective counter-narcotics force, while the show of force in the Caribbean may be to test if there are any officers in the Venezuelan military willing to reach out to the United States, in order to plan a coup against Maduro. ‘Currently, no one outside the country has good relations with Venezuelan generals, not even in Brazil or Colombia. So, you need to build those connections first.’

The Navy deployment has nothing to do with fighting drug cartels. It is entirely political, and it is being used by interest groups to use the U.S. military to bring about regime change in Venezuela. To explain this, let’s look at where the Cartel de los Soles narrative comes from, and why it was promoted in the United States in 2020 and now in 2025.

The origins: Displaced elites try to convince Uncle Sam to intervene

First, we need to consider how, as soon as Chávez came to power, Venezuela entered a period of extreme political polarisation. While the lieutenant colonel-turned-politician tried to push through radical reforms, many in the elites and middle classes decided he had to be removed from power at all costs.

Chávez entered the presidential palace of Miralfores in January 1999. By 2002, he was facing a military coup d’état and, between 2002 and 2003, a strike led by executives and managers in the oil sector. In 2004, María Corina Machado, who we now know to be the opposition’s most prominent leader, accused the president of rigging a referendum’s results, although the Organization of American States and the Carter Center said there was no evidence to back her claim—the latter was instrumental in documenting irregularities in 2024.

Herein lies a big problem. Perfectly reasonable people would have come out to deny those preposterous theories. But, if the priority was to put an end to Chavista rule, many thought, it would be best to let those lies spread.

It is thus that opposition activists used real cases about the coopting of high-level government officials by drug trafficking—a regional phenomenon, as we showed in the previous piece—to manufacture a political narrative of a ‘narco-state.’ Still, to this date they have not provided proof of a unified, hierarchical cartel which they claim exists. Again, we found that none of the DEA National Threat Drug Assessments even mentioned the existence of a so-called Cartel de los Soles. In this environment, instead of focusing on the real crimes, it became acceptable to make just about any claim, no matter how absurd, as long as it was directed against the government.

In Boomerang Chavez (2015), Emili J. Blasco says that the Venezuelan state under Chávez would have moved ‘up to 90% of Colombia’s cocaine production towards the United States and Europe.’ Of course, the author offered no supporting evidence, not even an anonymous statement. The claim was nonetheless repeated by opponents to Chávez and Maduro, because it served their political objectives. It is even used as a source in the Wikipedia page on the Cartel de los Soles. But we can prove that this statement is false. The Consolidated Counterdrug Database estimates that between 2012 and 2019, 13,703 tons flowed out of Colombia, and 1,376, or 10%, from Venezuela.

Sometimes, people and organisations spread false claims accidentally, by not verifying facts before they share them. Transparencia Venezuela, an anti-corruption watchdog, said in a 2024 release that, ‘according to a DEA report, almost 24% of global cocaine production transits through Venezuela.’ If Colombia produced at least 2.644 tons of cocaine, then we would be talking about 639 tons. It then moved on to calculate the size of the drug-trafficking sector in Venezuela based on this assumption.

The problem is that the DEA never said that. Instead, the NGO quoted an article that misquoted the DEA 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment, which spoke of 16% transiting through the ‘Western Caribbean vector’ and 8% through a different ‘Caribbean corridor.’ As demonstrated by the map below, only the third option matches more closely with Venezuela’s geographical location, although the report does not state that any of these vectors is specific to the country.

The Transparencia Venezuela report concluded that ‘it can be assumed that there was a gross income of USD 8.236 billion in 2024’ for the country. But as we know, this figure is based completely on false assumptions. Then, this has been used by Maduro’s opponents to claim that narcotics trafficking generates more revenue than oil, the by far largest sector in the economy. Because then, Venezuela would be ruled by a narco-state needing international intervention—namely by the United States.

The idea of branding Venezuela a narco-state has grave implications. It has been used to invoke the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (also known for its Spanish acronym, TIAR). The idea is that since we are dealing with a failed state overrun by criminal organisations, it is legally and morally right for governments across the Americas, with the United States at their forefront, to intervene militarily. For some in Venezuela’s opposition, like Machado and Iván Simonovis, it was the best-sounding strategy: have Uncle Sam get rid of Maduro.

David Smilde is a Sociology professor at Tulane University, New Orleans. He has researched Venezuela for over 30 years and published 5 books on the country. ‘This phenomenon is a classic way in which displaced or marginalized elites seek to gain power in authoritarian contexts, especially when they are unable via other means like elections or protest movements,’ he said. ‘They have tried to achieve this for years, arguing Venezuela harbours terrorist camps or Iranian missiles, threatens stability in the region, or is a national security threat to the United States. They use their access to international media and sympathetic think tanks to push these narratives.’

In the July 2024 presidential election, the opposition said it had won by a 37-point margin, and produced voting machine receipts to back it up. Maduro nonetheless claimed victory and remains in power. Since then, Machado has been on a media and lobbying offensive alongside her allies to build an international pressure campaign to remove him from power, including branding him the leader of the Cartel de los Soles.

But some Venezuelan politicians pushing a narrative is not enough. There are political and economic groups inside the United States that have adopted this story to advance their own interests, at specific moments.

‘Officials at the State Department and staffers on Capitol Hill see a continual flow of people coming in with crazy ideas about why the U.S. should intervene in their home countries,’ said Smilde. ‘They usually dismiss them, but sometimes they fit their plans. Some members of Venezuela’s opposition remind me of Ahmed Chalabi, the Iraqi politician who lobbied to push the idea that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, and so a military operation was necessary. We later found out that most of the information he provided was false.’ Ahmed Chalabi went on to lead the political transition after the 2003 invasion and was later appointed Minister of Oil and Deputy Prime Minister. But, as we know, he was not alone; his claims fit in with the designs of the George W. Bush administration.

Regime change plans fail in 2020

When did the Cartel de los Soles idea really take hold in the United States? We must go to March 2020, when the Justice Department first indicted Maduro and other high-level government officials. That was right when the Trump administration was carrying out a ‘maximum pressure’ campaign to produce regime change in Venezuela.

Actually, that was when the campaign was starting to wane in strength. From 2017 through to 2020, the U.S. Treasury introduced and tightened sanctions on Venezuela’s financial and oil sectors, dealing devastating blows to its economy. In January 2019, Washington, DC, also recognised the speaker of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, as the legitimate president, and supported the creation of a parallel, so-called ‘Interim Government.’ As President Trump said at the time, ‘all options are on the table,’ referencing the possibility of military action.

But by the year’s end, the mood had changed. Without being able to bring about regime change, Guaidó’s popularity started to falter. Large numbers of Venezuelans were still opposed to Maduro, but they were not willing to follow the self-proclaimed ‘interim president’ anymore.

In early 2020, the Trump administration was discussing the possibility of a military intervention in the South American country, as then Defense Secretary Mark Esper narrates in his book, A Sacred Oath: Memoirs of a Secretary of Defense During Extraordinary Times (2022). The strategy was being proposed by National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien and his Senior Director for Western Hemisphere Affairs, Mauricio Claver-Carone. But neither Esper nor various other cabinet members liked the idea of sacrificing American lives and resources for this objective, especially when he argued that many vital contingencies were not being considered.

Eventually, Attorney General William Barr was able to redirect President Trump’s attention, saying it would be better ‘to stop the flow of drugs towards the United States, especially from Venezuela.’ The president selected this less costly option. O’Brien and Claver-Carone eventually accepted it; ‘they wanted more but they were satisfied that we all wanted to do something bigger after years of inaction,’ Esper writes.

In practice, what did happen is that the Justice Department indicted Maduro, Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino, and regime heavyweight Diosdado Cabello, among others, offering rewards of up to $10 million for information leading to their arrest. The United States deployed Navy and Air Force units to the Caribbean in an officially counter-narcotics operation. Although it did little to nothing to curb drug trafficking, it captivated headlines. This result is something that President Trump has consistently favoured during his two presidencies, which was also remarked by Esper in his book.

The U.S. military did not take action inside Venezuela, however. Of course, not everyone was satisfied. The opposition in exile still attempted to trigger an armed intervention by sending mercenaries and army deserters into the country, led by former Green Beret Jordan Goudreau, in what was later known to be Operation Gideon. It failed upon landing, with six being killed and a further 91 captured. In his account, Esper hints that Claver-Carone and O’Brien were well aware of the preparations, while there are unconfirmed reports of knowledge or involvement by some U.S. agencies, though not by President Trump.

To summarise it all, the idea of pushing the Cartel de los Soles narrative at the time was to start an orderly retreat. Show the world that the Trump administration was being tough on Maduro, using the might of the U.S. military to intimidate him, but without actually doing anything to harm him.

Geoff Ramsey, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, explained that while 2020 began with the indictment of Venezuela’s ruler, ‘it ended with Trump saying he regretted supporting the Interim Government, and that he would be open to meeting Maduro,’ in this Axios interview.

Rescuing regime change plans in 2025

Many things have changed since 2020. But the reason why the Cartel de los Soles is resurging now is mostly due to the same reason. Even as President Trump is not sold on the idea, and has wanted to keep his distance from Venezuela’s opposition, other voices in Washington, DC, are still very much in favour.

Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Marco Rubio has been a longtime supporter of regime change in Venezuela. We could say that he owes his career to the Cuban-American exile community, which more recently has been joined by Venezuelan exiled elites in South Florida. The same applies to his congressional allies, like Carlos Giménez, Maria Elvira Salazar, and Mario Díaz-Balart, and others like politician-lobbyists Mauricio Claver-Carone —remember him? —and Carlos Trujillo.

Not all are Republicans; we could include longtime Democratic Senator Robert Menéndez, although he recently fell from grace after he was indicted and then convicted for receiving bribes from a foreign government. And very often, they have seen eye to eye with ‘hawks‘ or ‘neoconservatives’ who, unlike President Trump, are very eager to intervene in other countries’ internal affairs, like John Bolton and Elliot Abrams, two leading proponents of regime change in Venezuela in 2019.

In this close-knit Cuban-American political community, the objective is the liberation of the mother island from communist rule, while domestic issues take the back seat. We could also say that they have one of the least successful lobbies in history; while they are able to pass legislation to impose harsh sanctions on Cuba, they have not been able to trigger political change in over 60 years.

Venezuela is crucial in their equation. They believe that the two regimes need each other to survive; Havana needs Venezuelan oil, and Caracas needs the Cuban intelligence services. Having been unable to topple the Castros, the South Florida clique has increasingly turned its attention to Venezuela, where success seems more attainable.

Now here is a key element: Rubio has been able to transform his discourse to fit in with President Trump’s language, so intervening in Venezuela can fit inside the America First agenda. How? Argue that the country is run by a narco-terrorist organisation that is a threat to the national security of the United States. So instead of moving against a foreign government, it’s about targeting the Cartel de los Soles.

It is no surprise that this approach has delivered contradictory outcomes. And Rubio, and his Cuban-American and Venezuelan allies, calling for an intervention would be caught right in the middle of them. Much of the Trump administration has taken on the idea of the Cartel de los Soles and the Tren de Aragua as its operational arm, not to seek regime change but to force through an ambitious immigration agenda. The narrative here is that former President Joe Biden’s policy was to allow terrorist gangs into the United States, and it is time to send them home.

Barely into his third month, President Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to speed up the deportation of Venezuelan migrants by suspending their rights to due process, and sent 250 of them to El Salvador. ‘The idea of a Cartel de los Soles has been promoted by certain figures in the Venezuelan opposition to promote an intervention, but it’s been repurposed by Trump to stigmatize Venezuelan immigration,’ said Smilde.

For the Cuban-American political world, this was a hard sell. The very same administration is trying to terminate all special immigration protections for Venezuelans and Cubans, including Temporary Protected Status and Humanitarian Parole. Voters will be U.S. citizens, just as most donors. But in this community, many have relatives and friends who are being affected by this sudden change in immigration policy. This means that their fairly safe House seats could now be at risk.

According to Geoff Ramsey, the Trump administration is engaging Venezuela from two angles. First, it has an approach ‘for the cameras.’ Deploy the military and carry out strikes against drug trafficking vessels. Then, the second prong is about ‘advancing U.S. interests in immigration, energy, and other strategic issues.’

After the Treasury cancelled licenses for oil companies to work in Venezuela, it issued a new one on July 24, so that Chevron could resume its local operations. Deportation flights from the U.S. to the South American country continue, with a twice-weekly frequency.

President Trump is also using the military to deal with political and law enforcement issues domestically, which gives him greater freedom to act as the executive and has an important media impact. Examples include not only the Navy deployment in the Caribbean, but the proposal to strike cartels inside of Mexico, or using the National Guard to fight crime in Washington, DC and against protests in Los Angeles. ‘Maduro has done the same too, for example with his offensive against crime called Operación Liberación del Pueblo,’ said Smilde.

Incidentally, it was right after the new Chevron license, on July 25, that the U.S. Treasury sanctioned the Cartel de los Soles as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist—although it did not sanction any concrete individuals or entities. This was followed by the Justice Department increasing the bounty on Maduro to $50 million.

‘There’s a reason why Trump talked about the Tren de Aragua (TdA), and not the Cartel de los Soles,’ said Ramsey, referencing the recent air strike against a boat alleged to be carrying drugs from Venezuela. ‘Trump is looking to deport hundreds of thousands of Venezuelan migrants. To do this, he’s invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, and the entire justification is that the TdA is invading the country.’ The second, necessary leg is that the gang is acting at Maduro’s behest and thus constitutes an invasion by a foreign state.

‘TdA has been designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), which means that anyone accused of materially supporting them can be prosecuted under U.S. law,’ said Ramsey. ‘But if you look at the Cartel de los Soles, it has received a lesser Treasury Department designation. This is likely because the U.S. is trying to carve out space for Chevron and other companies to continue operating in Venezuela, without being accused of materially supporting a terrorist group.’

When asked as to why the Trump administration is combining two approaches, Ramsey argued that ‘there are a lot of people frustrated by the idea of sanctions relief and the end of Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelan migrants, as the priority is to push an immigration agenda.’ Hence, the for-the-cameras approach would be to soothe their concerns without hindering the real objectives.

Meanwhile, the military deployment ‘may be the only thing where everyone in the administration can agree on,’ said the former Pentagon official. While Rubio can try to take advantage of it as a regime change manoeuvre, America First supporters are happy believing the U.S. government is being tough on crime.

Economic interests behind the narrative

There are also economic interests at play. The South American country is well known for having the world’s largest oil reserves, with 303 billion recoverable barrels of crude, which is 17.5% of the globe’s total. It also has the seventh-largest natural gas reserves, and significant deposits of gold, iron, coltan, tin, bauxite, tantalum, and platinum.

Over the last year, María Corina Machado has sold Venezuela as the ‘1.7 trillion dollar opportunity,’ which just needs Maduro gone to materialise. She has virtually attended many important international business events, to promote this idea, including CERA Week 2025, an energy conference in Houston. With this in mind, it is no surprise that economic interests would sign up to the idea of regime change.

Now, we already know some usual suspects. It sounds obvious that Chevron would lobby to obtain a license to work in Venezuela, and thus recoup its investments and debts in the country. But ExxonMobil has also been an active player lobbying and funding think tanks on issues relating to Venezuela.

The largest U.S.-based oil company and the Chavistas have a lot of bad blood. ExxonMobil left Venezuela after Chávez introduced reforms where private oil companies were forced to accept a majority stake by state-owned PDVSA. The corporation first tried to claim this nationalisation as unlawful, but an arbitration tribunal ruled that it was not illegal, while it was still awarded close to $1.6 billion. It would not be strange for ExxonMobil to attempt a comeback. And in the meantime, it has also set its foot in neighbouring Guyana, giving it a few billion reasons to want an isolated and weak Venezuela.

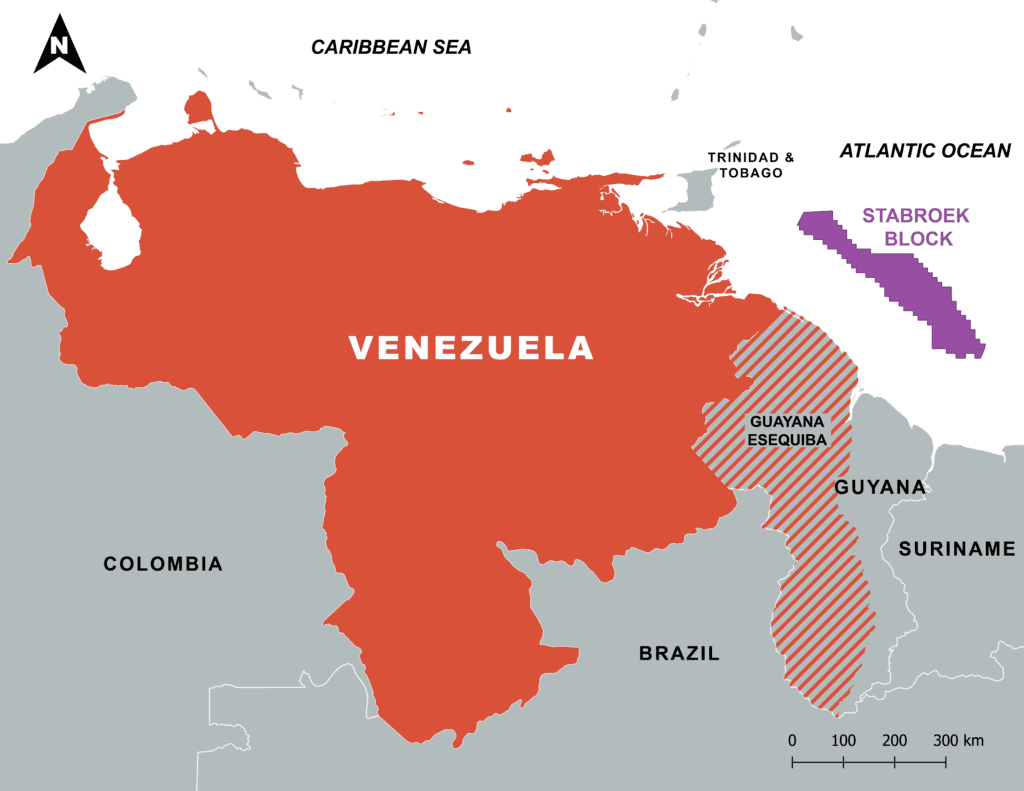

Guyana has a latent territorial dispute with Venezuela, which now matters for one key reason. The waters just off the contested Essequibo territory contain 11 billion barrels of light oil, in the Stabroek offshore block. The exploitation of these resources has turned Guyana from one of the poorest countries in South America to the richest in GDP per capita terms in just five years.

ExxonMobil leads a consortium in Stabroek, alongside Hess—recently acquired by Chevron—and CNOOC. The success of the oil block, and of Guyana, depends on not being interrupted by the territorial dispute. A military conflict over it is unlikely, but what if there was an effort to negotiate a peaceful resolution? It could make both countries divide royalties or put them in an escrow account. Or the consortium could cease to enjoy an exceptionally low government take, if Caracas imposed its regulations. Any of this could happen if, God forbid, relations with Venezuela were normalised.

In 2017, when the first Trump administration imposed the first round of sectoral sanctions, it was Rex Tillerson, a former ExxonMobil CEO, who was Secretary of State. That was also when the very same U.S. corporation was carrying out the first stages of the Stabroek project, which would make the small South American country’s economy explode from 2020 onwards.

Guyana is also where we find Mauricio Claver-Carone. Remember him? Yes, the politician who was pushing for a military intervention in Venezuela. Besides coming from the Cuban-American political community, he is also the manager and general partner of the LARA Fund, which has investments in Guyana, betting on the country’s fast economic growth.

Promoting the Cartel de los Soles narrative helps the Cuban-American faction in South Florida to cover up their failures. It also helps economic interests prevent a normalisation with Caracas, which could upend plans in the Stabroek offshore oil block.

The Venezuelan scapegoat

As we can see, to some interest groups the idea is not even about regime change, but just scapegoating and virtue signalling. We have already discussed how the South Florida clique has grown by vilifying regimes in Cuba and Venezuela. Other political and economic interests have latched on to the Cartel de los Soles narrative, as sometimes it means scoring easy points. ‘There is nobody more stigmatized and discredited than Nicolás Maduro. Nobody’s going to say he’s a good guy. So you can really say anything about him and nobody will take exception,’ said Smilde.

In some Latin American countries, the Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua narratives have also been useful to some politicians. That is why the governments of Paraguay, Ecuador, Argentina, and Peru have declared the alleged group a ‘narco-terrorist organisation’ over the last month. But if Maduro’s criminal empire has been threatening the region’s peace for over a decade, why start now?

First, the timing has one big reason: the State Department is on a regional push for all capitals to adopt this measure. So far, the presidents that are more closely aligned with Marco Rubio have been quick to accept, while others have rejected the Cartel de los Soles narrative as unfounded, like Colombia’s Gustavo Petro and Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum.

In fact, Bogotá pushed this narrative from 2019 to 2022, during former president Iván Duque’s time, while he was part of a Washington-led effort to isolate Maduro. He took the devastating decision of shutting down all relations with Colombia’s most important neighbour, Venezuela, including closing the border. When Petro came into office, he took a more pragmatic approach to bilateral relations, reopening diplomacy and trade, and dropping unfounded claims on the Cartel de los Soles. It is therefore strange that Colombia’s government would only consider such a notorious group a threat for three years.

Then, the narcoterrorism designations also work for internal politics within each of the countries. In Ecuador, the ruling party used this issue to insinuate the opposition is in bed with Maduro’s alleged criminal groups, the Cartel de los Soles and the Tren de Aragua. Similarly, to scapegoat Venezuelan migrants for a rising crime wave, which is mostly attributed to the shift in global cocaine trafficking routes towards Ecuador. Almost simultaneously with the designation, the country’s National Assembly voted to end a migration agreement with Venezuela.

This is another problem for Latin America: scapegoating Venezuelan migrants and bashing Maduro are low-cost methods to boost polling numbers in the region; this is then combined with the U.S. State Department’s demands as it once more tries to isolate Venezuela. Although perhaps political leaders could focus on reducing inequality or cooperating on security, with genuine support from Washington, DC.

We need to step back from the brink

‘Marco’s War’ is how a number of commentators are describing the U.S.’s increasingly bellicose actions towards Venezuela. The Secretary of State has indeed picked up and run with the false ‘Cartel de los Soles’ narrative, a sleight of hand to attempt to win support for discredited, dangerous neoconservative policies. This investigation, our second on the subject, explains the real driving forces behind U.S. Venezuela policy – and no, it’s not American national security, which is best served by constructive engagement, not extra-judicial killings and reckless pronouncements in pursuit of regime change.

Our third investigative report, to be released shortly, looks at the cost of the sharp neoconservative turn in U.S. Venezuela policy. The empowerment of foreign adversaries; the damage to the U.S. energy industry; and the fundamental undermining of American diplomacy in Latin America are all to come.