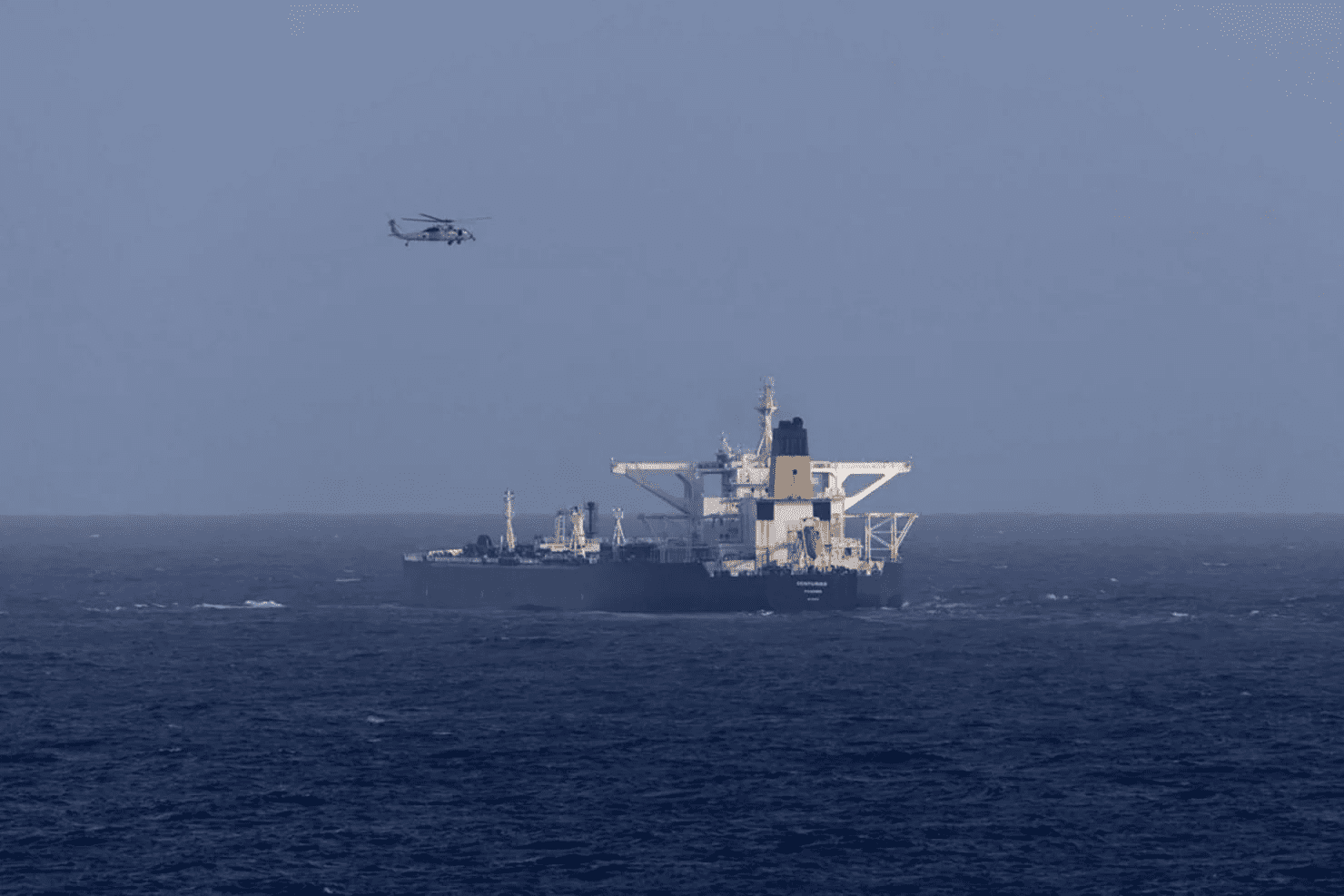

The Amuay refinery, within the Paraguaná Refining Complex, in Venezuela’s state of Falcón. According to unofficial sources, a Chinese company sanctioned by the U.S. is reportedly entering its operations through a services contract. Photo: Luis Ovalles.

Guacamaya, June 8, 2025. An alleged list of companies that signed “productive participation contracts” (CPPs) with PDVSA was recently leaked. There has also been talk of a growing role for Chinese companies in Venezuela as U.S. sanctions intensify.

The Venezuelan government has also made grand announcements of investments and official visits by foreign oil companies. These include the Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO), Russia’s TNG Group, and Nigeria’s Oranto Petroleum. Meanwhile, political activist Iván Freites claims on social media that “China is taking control of PDVSA.”

But what do we really know about the most recent agreements and investments in the Venezuelan hydrocarbons sector? Through Orinoco Research, it has only been possible to confirm or deny some of this information. A large part of the industry is working under darkness, protected by the “Anti-Blockade Law.”

What is the CPP? What list?

The CPP is a production-sharing agreement (PSA), which allows private investors to take barrels of crude—up to 55% in some cases—as payment for operations and services in oil fields. It also incorporates other elements, such as the private investor also being responsible for buying goods and services.

The CPP was born with the Anti-Blockade Law of 2020, created by the National Constituent Assembly to respond to U.S. economic sanctions. In this case, it creates an oil production agreement that is much more profitable than the main model in Venezuela, the joint venture, in which PDVSA is required to be the majority partner.

This “default” framework became unprofitable in many cases, especially with the addition of special taxes. That’s why both CPPs and other service contracts, as well as the joint venture format known as the “Chevron model,” were created.

On to the list. The leaked plan includes nine companies that have reportedly signed CPPs with PDVSA, according to sources within the Venezuelan state-owned company. In total, the 13 projects would aim to reach a production plateau of 890,000 barrels per day, with a CAPEX investment of $32 billion. This could represent the bulk of the calculations made by the Minister of Industry and president of the International Center for Productive Investment (CIIP), Alex Saab: that there are already $52 billion in “tied-up investments.”

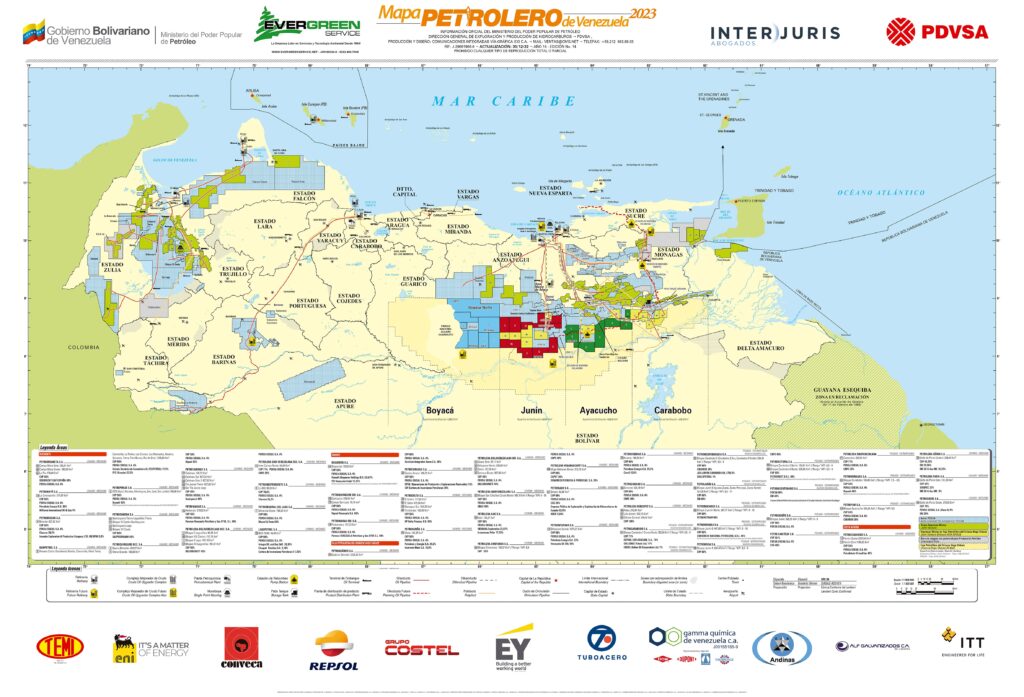

The projects are spread across two of the world’s largest hydrocarbon deposits: the Lake Maracaibo basin, in the West of the country; and the Orinoco Oil Belt to the East.

Although the oil industry has historically focused on Lake Maracaibo, the majority of Venezuela’s crude reserves are located in the Belt, which follows the northern bank of the Orinoco River, spanning across the states of Guárico, Anzoátegui, and Monagas. With 258 billion barrels of crude oil, it is comparable to Canada’s Athabasca Oil Sands.

“Maduro is handing PDVSA over to the Chinese”

The company most mentioned in the media has been China Concord Petroleum. Based in Hong Kong, it has already been sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) for business dealings with Iran. It has reportedly agreed to operate two blocks in Lake Maracaibo, which would partially overlap with the joint venture Petrolera Bielovenezolana. As the name indicates, it is a—now dormant—partnership between PDVSA and Belorusneft.

There are also unofficial reports that China Concord is servicing the Paraguaná Refining Center, the complex with the second largest installed capacity in the world. However, this information has not been confirmed.

Anhui Guangda Mining Investment Co., a mainland Chinese company, has also reportedly signed a CPP for the Ayacucho 2 block. In the Orinoco Belt, this would be a greenfield project, unlike others in which private investors are benefitting from already existing infrastructure.

According to the company’s website, its president, Zhang Daofu, met with then-Venezuelan Oil Minister Pedro Rafael Tellechea in January 2024.

According to unofficial sources, Kerui Petroleum also signed a memorandum of understanding with PDVSA. However, there is no information that this company has made any progress. Kerui did provide services to wells in Lake Maracaibo in 2016.

North American Investors and their Bets, Besides Chevron

In April 2024, LNG Energy Group announced that it had signed CPPs to operate two blocks in the Orinoco Oil Belt: Nipa-Nardo-Niebla and Budare-Elotes. However, the company added that its operations could only be carried out with OFAC authorization.

LNG Energy is a company that primarily produces hydrocarbons in Colombia, although it is listed on the Canadian TSX Venture Exchange. It is common for mining and hydrocarbon companies to have financial headquarters in Canada, where they find a favorable environment.

North American Blue Energy Partners (NABEP) is affiliated to Global Oil, the which is in turn owned by Florida magnate Harry Sargeant III. It has reportedly managed to increase production at Petrozamora, on Lake Maracaibo, from 25,000 barrels per day in early 2024 to more than 55,000 this year.

This year, it reportedly began new operations in Junín Sur and Petrocedeño, in the Belt. The latter project includes one of four crude oil upgraders in Venezuela, now the only one operating alongside Petropiar, a joint venture between Chevron and PDVSA.

The fate of NABEP’s operations in Venezuela is unknown after the U.S. Treasury Department canceled all licenses, as well as that of other Western companies.

There is also a case in the world of joint ventures: Amos Global Energy, a company owned by Ali Moshiri, the former president of Chevron Africa and Latin America. Paradoxically, a U.S company—along with the fund Gramercy—signed the purchase of the 32% stake held by the Chinese state-owned Sinopec in Petroparia. However, as expected, they need an OFAC authorization to begin operations in Venezuela.

Petoparia is an offshore project in the Gulf of Paria region, as its name suggests, near the island of Trinidad. It is projected to sit over significant oil and gas reserves. It is also adjacent to the Petrosucre and Petrogüiria joint ventures, in which Amos Global Energy is also reportedly interested.

Small, more or less unknown companies

The list of companies that have signed CPPs or similar contracts includes other relatively small companies in the oil world, largely unknown to the general public, in contrast to giants like Chevron or Repsol.

The best known is Aldyl Argentina, with a presence in Vaca Muerta, in its home country. It reportedly signed an agreement for the Morichal field in the Orinoco Belt. Production from that field has risen from 45,000 to 65,000 barrels per day in the last year, although it is unknown to what extent this is due to PDVSA’s own efforts or to production-sharing agreements.

Also on the list are the Alvarado & Cladoca Consortium (Brazil); Miller Energy Trading (Turkey); Accumes Holdings (Switzerland); and Vulcan Energy Technology (Germany and Australia). This information, provided on the list, has not been confirmed.

The military company Camimpeg would also have a services agreement for the Ambrosio field in the West of the country. It is in turn part of a joint venture with the Anglo-French company Perenco, which, despite being a shareholder, no longer operates in Venezuela.

New Stratus Energy: In and Out in Less than a Year

In 2024, José Francisco Arata, a former PDVSA executive, brought New Stratus Energy (NSE) into a joint venture in Venezuela. The firm acquired 50% of GoldPillar International Fund, owned by Italian businessman Francisco Favilla, who facilitated the deal. Favilla also earned a finder’s fee of $8.5 million.

Goldpillar, in turn, became a partner of PDVSA with a 40% stake in Petrolera Vencupet, a joint venture initially created with the Cuban state oil company CUPET.

Already by the end of 2024, this project was terminated. In a press release, NSE claimed the reasons were: “The inability to recover invested capital under the original contractual arrangements; the deterioration of the investment climate for foreign investors in Venezuela; the cancellation of all foreign licenses by the Trump Administration; and the availability of alternative investment opportunities deemed more viable and strategically aligned with the Corporation’s objectives – specifically Block 60 in Ecuador.”

What about “South-South” cooperation?

What happened to the companies mentioned above? TPAO from Turkey, TNG from Russia, and Oranto from Nigeria. The truth is that it’s common for large deals to be announced with foreign companies, mainly from allied countries, without any investments ever materializing. There has also been talk about the Iranian state oil company, which has yet to venture upstream in Venezuela, despite extensive cooperation between Tehran and Caracas.

On the other hand, the capital that does arrive in Venezuela usually does so quietly. Some of the projects mentioned in that famous list are already well underway, while investors have managed to produce and sell the first barrels.