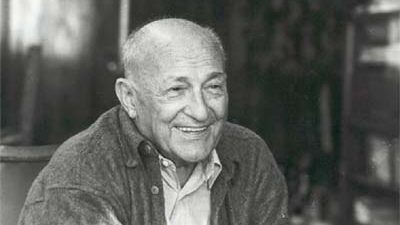

Economist Francisco Rodríguez is the founder of Oil for Venezuela, a non-profit seeking solutions to the country’s humanitarian crisis. Photo: Arnaldo Espinoza.

Guacamaya, June 18, 2025. Francisco Rodríguez is a renowned Venezuelan economist, who is now a professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. For years he has sought to influence the politics of his native country and to find solutions to the humanitarian crisis, even from the United States. He has just published the book The Collapse of Venezuela: Scorched Earth Politics and Economic Decline, 2012-2020 this year.

His main initiative today is Oil for Venezuela, which we discuss extensively in the interview. He has also served as an economic and financial advisor to the National Assembly from 2000 to 2004; Head of the Research Team at the United Nations Human Development Report Office from 2008 to 2011; and Chief Economist for the Andean Region for Bank of America from 2011 to 2016.

He is the author of several academic studies and analyses on his country’s economic decline, while recently he has focused on sanctions and the political conflict, subjects on which there is much to discuss. Among his publications stand out: Venezuela Before Chávez: Anatomy of an Economic Collapse (2014), The Collapse of Venezuela: Scorched Earth Policy and Economic Decline, 2012–2020 (2025), and The Human Consequences of Economic Sanctions (2024).

Q: I want to refer to the UN “Oil for Food” program. It was an initiative of the Security Council to alleviate the humanitarian situation in Iraq after the severe sanctions imposed against Saddam Hussein’s government, following the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the Gulf War in 1991. In the book Cooperative Responses to the Crisis in Venezuela, of which you are a coauthor, this case is mentioned as a precedent to the proposal you developed. What lessons do you draw for the Venezuelan case?

The Oil for Food program is a very relevant precedent for the Venezuelan case. When the Security Council imposed sanctions on Iraq in 1990, it was thought that a quick resolution of the conflict would be achieved, either because Saddam Hussein would resign or because he would comply with the demands regarding inspection of facilities. But this did not happen, and the sanctions remained in place, triggering a large-scale humanitarian crisis in Iraq.

The growing concern about the humanitarian effects of these sanctions led the Security Council to rethink the scheme. Key here was the pressure from other countries in the region and also the emergence of academic evidence showing how the sanctions were seriously affecting the health and nutritional conditions in the country. This led to an increasingly widespread demand for a reform of the sanctions regime, which culminated in the creation in 1996 of the Oil for Food program.

This program allowed Iraq to sell oil under an international monitoring and supervision system that ensured that the revenues were used exclusively for the purchase of essential goods and services. The results were concrete and measurable: there was an increase in caloric consumption and significant improvements in health and nutrition conditions. The program proved to be a viable alternative and produced substantial improvements for Iraqis in contrast to the indiscriminate sanctions regime that had preceded it.

Unfortunately, the program was also marred by a corruption scandal involving senior United Nations officials, which left a negative perception in some sectors. In our book Cooperative Responses to the Venezuelan Crisis, we contextualize that episode within its true dimension and study how a program of this kind could and should be redesigned for the Venezuelan case, in order to minimize corruption risks.

It is interesting to note that today, in the Venezuelan case, we are exactly six years from the initial imposition of sectoral sanctions on the oil sector, exactly the same period that elapsed in Iraq between the imposition of sanctions and the adoption of the Oil for Food program. Despite the recent tightening of sanctions by the United States, I perceive a growing awareness — both in the international community and within the country — about the very damaging effects that these sanctions have had on the living conditions of Venezuelans.

“I don’t want Venezuelan oil wealth to belong to either the Americans or the Chinese: I want it to belong to the Venezuelans.”

Q: Regarding the suspension of oil licenses, Juan González, then advisor for the Western Hemisphere to former President Biden, said that the only winner would be China. And recently we’ve seen greater rapprochement with Russia, Iran, and China. Do you think González was right?

A: I don’t know if China is really going to be the one to come out winning, but what I am convinced of is that the one who is going to come out losing is Venezuela.

As for the specific case of China, there are two views. One is the one expressed by Juan González, among others, which holds that the tightening of sanctions by the United States is leaving the path open for China. The other view, generally held by advocates of a hard line, argues that the previous period of maximum pressure — particularly around 2020 — did not lead to a significant increase in Chinese investment in Venezuela. According to this argument, China’s appetite for investing in Venezuela was considerably reduced due to past experiences.

My impression is that the reality is somewhere in between. It is clear that if the United States prohibits buying oil from Venezuela and restricts its companies from investing in the country, it is leaving the field open for companies from other nations to do so, especially those — like the Chinese — that do not consider the threat of secondary sanctions to be a significant obstacle. That said, I also recognize that we have not seen clear signs that China, or other actors, are planning massive investments in the country.

I must confess that, as a Venezuelan, there is something about this discussion that bothers me. It seems as though the only relevant debate is whether Venezuelan oil resources will end up in the hands of the Americans or the Chinese. In fact, there has been a clear strategy on the part of some sectors that oppose the tightening of sanctions, who have tried to frame the debate in terms of the “America First” vision to convince the Trump administration that it must act to ensure that Venezuela remains within the U.S. orbit.

As for me, I don’t want Venezuelan oil wealth to be either the Americans’ or the Chinese’: I want it to be the Venezuelans’. I think this episode is yet another example of the tragedy the country has fallen into as a result of the destructive conflict between two political factions vying for control of the nation, in a logic reminiscent of the Cold War, in which internal actors offered the country’s resources to foreign powers in hopes of securing the highest bidder.

In any case, I am convinced that, when Venezuela has the opportunity to rebuild its economy, it will do so with the effort of the Venezuelans themselves, the same ones who were capable of building a national oil industry that, at one time, became one of the most efficient and profitable in the world.

Q: In 2019, you, together with the Oil for Venezuela Foundation, proposed a Humanitarian Oil Agreement. How would you bring that proposal into the context of Venezuela in 2025, after the suspension of licenses to Western companies?

A: The proposal for the Humanitarian Oil Agreement was precisely an attempt to design an institutional structure that would allow Venezuela to reenter the international oil market, while at the same time learning from the lessons of Iraq’s Oil for Food program, with the goal of not repeating its mistakes.

Part of the proposal responded to the institutional reality of that moment. In 2019, there were two governments disputing international recognition. One of them, the so-called interim government, at that time had control over the country’s external assets and the recognition of dozens of countries. That reality has changed, although it has not entirely returned to the previous situation. Today the interim government has disappeared, but it remains true that the United States recognizes the National Assembly elected in 2015 as the legitimate representation of the Venezuelan state.

There is, however, an element of that proposal that I consider very relevant to the current context, and that is the idea of building solutions based on co-governance schemes. This implies achieving humanitarian agreements in which the parties to the conflict agree to the creation of autonomous institutions that have representation from both sides or, at least, an agreement on the profiles and characteristics of those who should be in charge of those institutions. It is, essentially, about rebuilding parts of the Venezuelan state — especially those in charge of resource management — on the basis of cooperative agreements, prioritizing addressing the urgent problems of the population over political conflict.

Even though I do not agree with the suspension of the licenses, I believe that the current juncture could open an interesting opportunity. Between the two opposing views — those who advocate for the total suspension of licenses and the return to the “maximum pressure” strategy, and those who wish to return to a regime of easing or progressive lifting of sanctions — an intermediate path could be explored. For example, we could agree on mechanisms through which the resources generated by oil sales — including those sales made under specific licenses in the United States — are managed under international supervision, within institutions arising from broad political agreements.

Naturally, these agreements would have to adapt to a reality different from that of 2019, because the relevant actors — the stakeholders — have changed. But the principle remains valid: to create shared governance structures that allow for a response to the humanitarian emergency without subordinating to the logic of conflict.

“We are in a conflict where everyone is losing: the nation is losing, the citizens are losing, and the opposing parties themselves are also losing. And when the conflict is generating widespread losses, there is more space to think about cooperative solutions.”

Q: In the book Cooperative Responses to the Crisis in Venezuela, it is stated that “the existing tensions between Russia and the Western world, which intensified with the war in Ukraine in 2022, may generate uncertainties that force modifications to the original ‘Oil for Venezuela’ proposal.” This was a humanitarian initiative promoted by you, whose objective was to alleviate the Venezuelan crisis, with a clear emphasis that it should not become a hostage of international geopolitics or of the commercial interests of any foreign partner. Nevertheless, in that same analysis it is suggested that Russia might not oppose a scheme of this kind in the Security Council, and might even actively support it.

What made you think that Russia would not oppose such an initiative? What modifications have you considered necessary in the proposal, given the changes in the geopolitical context that currently surrounds Venezuela? What role do you think countries like Russia, Turkey, or China could play in the framework of a humanitarian proposal of this kind?

A: The reality of the conflict between great powers — in particular between Russia and the United States, but also between the United States and China — is changing, and it has evolved significantly since 2019. It is also true that the position of the current Donald Trump administration, in this second term, is much more inclined to seek understandings with Russia. Therefore, I don’t think there is any reason to believe that an initiative aimed at building international support to move forward in resolving the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis could not prosper.

It must be remembered that the position of the United States toward Venezuela, at least since 2017, has focused on promoting regime change. When that is the declared goal, it is logical that a government like Maduro’s would approach those powers that are willing to protect it and include it in their sphere of influence. In that context, any proposal that seeks a change of government is unlikely to gain the support of actors like Russia or China, who oppose the isolation strategy pushed by Washington.

But here the logic is different. This is not an initiative to promote regime change, but a proposal aimed at improving the living conditions of Venezuelans and protecting them from the collateral effects of the conflict, both internal and international. In that sense, it is a proposal that benefits all parties. And I believe that both national and international actors should be willing to support it.

“The parties in conflict adopt what I call scorched earth strategies: they deliberately harm the economy thinking that this gives them advantages in their struggle for power.”

Q: What kind of reforms can be promoted to protect Venezuelans from the collateral damage caused by sanctions? Some of the proposals in which you have participated are based on the principle of shared power. There is the case of economist Dragoslav Avramović, who despite opposing the Yugoslav president, agreed to be appointed governor of the National Bank to combat hyperinflation and mitigate the effects of sanctions. But later he was dismissed for clashing with radical interests in Slobodan Milošević’s inner circle. What lessons can be drawn from your point of view as an economist from backgrounds like this for the Venezuelan case?

A: The idea of shared power initiatives, or what I also call the creation of co-governance institutions, is based on a diagnosis that I have developed in my work and that is summarized in my most recent book, The Collapse of Venezuela’s: Scorched Earth Politics and Economic Decline 2012–2020 (University of Notre Dame Press, 2025). A significant part of the Venezuelan problem has precisely to do with political conflict, and with our inability to design institutions that limit the effects that this conflict has on people’s living conditions.

One of the arguments I develop in that book is that there are contexts in which the conflicting parties adopt what I call scorched earth strategies: they deliberately harm the economy thinking that this gives them advantages in their struggle for power. So part of the question I have asked myself is how we can overcome that deadly, toxic, and destructive logic of Venezuelan political conflict.

There, a central element comes in: the idea of reducing what in English are called the stakes of power, that is, the relative benefits of being in power and the costs of being out of it. Co-governance is a way to reduce those asymmetries, so that the struggle for power does not become an existential struggle, and so that losers do not feel that acknowledging defeat is equivalent to political annihilation or even something worse.

I have suggested that these initiatives can occur at different levels. One level is that of sectoral agreements, such as a humanitarian oil agreement. There was also the proposal for the financing of the electricity sector, promoted by CAF in 2019, or the joint initiative to address the issue of vaccines during the pandemic. Added to this is the so-called social agreement signed in Mexico in 2022, which unfortunately was never implemented. All these are examples of cooperative sectoral agreements.

And then there is the more ambitious idea: that of a global shared power agreement, in the context of a central political negotiation, with the creation of institutions that guarantee the possibility of coexistence between the parties in conflict.

Of course, there are other international experiences of shared power. Not all have been successful, but I believe that the Venezuelan case — due to the characteristics of its conflict — has elements that make it conducive to such an approach. It is, essentially, a conflict where we are all losing: the nation loses, the citizens lose, and the warring parties themselves also lose. And when the conflict is generating widespread losses, there is more room to think about cooperative solutions.

In fact, I draw inspiration from the example of Poland in 1989: a country that could have fallen into a very destructive conflict and where the opposite happened. Even from a government that had lost popular support and had been defeated in elections, agreements were built that allowed a transition based on mutual guarantees. That transition ended up being one of the most successful toward a market democracy in Eastern Europe.

Q: In an article published in Foreign Policy, you highlighted the role that Iran played in 2020 so that the government of Nicolás Maduro could withstand the sanctions imposed by the United States. You also stated that “Iran has been sanctioned since 1979 and the early years following the sanctions closely resemble the current situation of Venezuela, as it also experienced a collapse in oil production. Later, Iran began a gradual recovery as the country adapted.” Likewise, you pointed out that the Venezuelan government has imitated measures adopted by Iran, such as the November 2019 decision to reduce traditional fuel subsidies, seek income from non-oil exports, or give a larger role to the private sector.

How important today, in the 2025 scenario, are those types of international alliances for the Maduro government? Is the Iranian model still a valid reference for Venezuela?

A: More than a model, I would say it is part of the natural evolution of sanctioned countries. Sanctions have a very strong effect at the time they are applied, but over time economies adjust. And they adjust because, naturally, they become less dependent on the actors with whom trade has been blocked.

What we see in the Iranian case is that Iran was hit very hard by the 1979 sanctions because it was a highly US- and Europe-dependent economy. But over time it reoriented itself toward Asia, particularly trade with India and China, and that made it less vulnerable.

I also believe that the Venezuelan case, over the past few years, has shown increasing rationality in economic policy. This doesn’t seem surprising to me; rather, it seems normal. It’s what countries do when they run out of money. Populist economic policy experiences do not occur in contexts of scarcity, but in contexts of abundance. And that was Venezuela’s case during Chávez’s period.

It remains to be seen, of course, what the outcome will be of this new episode of oil revenue decline, associated with the recent reduction of licenses. But what I observe so far points to the Maduro government attempting to adopt a scheme centered on deficit reduction through spending cuts and tax increases, and not a scheme based on more intervention or price distortions, as happened in 2016 in the face of the previous drop in income.

I do not doubt that there is communication and learning among these countries. But I believe that, once again, a basic logic is fulfilled: these are countries that tend to take the correction of macroeconomic distortions seriously when they run out of resources, among other things as a result of sanctions.

“The truth is that this figure of secondary tariffs on Venezuela is, from the beginning, a policy without any sense whatsoever.”

Q: The United States government has imposed 25% tariffs on goods imported from any country that buys oil from Venezuela, whether directly or through third parties. In 2020, the impact of secondary sanctions imposed on Rosneft was particularly significant: in 2019, Rosneft handled approximately 75% of Venezuelan oil sales and also supplied almost all the gasoline imported that year. Subsequently, the country faced an acute fuel shortage. How do you assess the consequences that a measure of this nature can have on the Venezuelan economy, both in terms of fiscal revenue and the impact on productive activity, transportation, and the daily life of the population?

A: Yes, certainly secondary sanctions are the most powerful instrument of economic coercion that the United States has. That the United States doesn’t buy your oil, in itself, would be a minor problem. The most relevant thing is that the United States uses its economic power to deter other countries from buying Venezuelan oil.

By the way, this reminds me of something I always repeat when I have the chance: the United States is the only country in the world that has imposed economic sanctions on Venezuela. There is a fairly strong consensus in the rest of the world not to impose sanctions that damage the Venezuelan economy and, therefore, Venezuelans. But of course, the United States is not just any country: it issues the world’s reserve currency, and the threat of losing access to the US financial system is enough to deter many companies from doing business with Venezuela.

That’s why the 2020 secondary sanctions move was very significant and played an important role in generating the fuel shortage and in the continued collapse of the Venezuelan oil sector.

Now then, I believe we are in a different moment. You mention the issue of the 25% tariff on goods imported from any country that buys oil from Venezuela. But the United States has not imposed that tariff. What President Trump did was grant Secretary of State Marco Rubio the authority to impose it. However, that tariff has not been applied. Therefore, it remains an unfulfilled threat.

And that leads us to ask why it has not been fulfilled. The truth is that this figure of secondary tariffs on Venezuela is, from the beginning, a policy without any sense whatsoever (although, to be fair, it would not be the first Trump administration policy lacking it). Imposing a 25% tariff on all imports from China because China buys oil from Venezuela is an overreaction that completely loses the sense of proportionality. It is, essentially, like punishing Walmart buyers because China buys oil from Venezuela.

Just a week ago, a court ruling suspended another Trump administration measure based on similar arguments of indirect retaliation. Although that ruling does not directly mention the secondary tariffs on China, everything indicates that any attempt to impose them would be quickly declared illegal and contrary to that decision.

Therefore, I believe this threat will come to nothing: it will not be implemented.

You also have to understand the broader context and how it differs from that of 2020. Secondary sanctions are only effective if they are dissuasive, and to be dissuasive, you need to have friendly trade relations with the actors you want to dissuade. And that is not currently the case with China.

The United States has come to impose tariffs of up to 245% on China, which are essentially prohibitive. In that context, a threat of a 25% tariff becomes irrelevant, because if tariffs already reach 245%, it’s irrelevant if you threaten to raise them to 270% — nobody is going to buy.

In this context, in which the Trump administration has decided to unleash a trade war against a good part of the world, it is very difficult for it to have the leverage it had in 2020 to dissuade the rest of the global economy from buying Venezuelan oil.

Of course, there may still be pressure on some European companies, like Repsol and ENI. But even there, the United States has to act with caution. Let’s remember that there is the European Union’s Blocking Statute, which protects European companies from unilateral sanctions imposed by the United States, such as those applied to Cuba, Iran, or Syria. I wouldn’t be surprised if, should the United States decide to escalate its pressure on Europe on this issue — within the framework of a broader trade conflict like the one some sectors of the Trump administration seem willing to push — the European Union decided to include Venezuela among the countries covered by the Blocking Statute.

“To me the issue is clear: if your strategy is to destroy the Venezuelan economy, then Venezuelans will flee a destroyed economy.”

Q: In the study “Sanctions and Venezuela Migration,” you conclude that a policy of “reengagement” with Venezuela, instead of isolation, could be more effective in controlling the migration crisis and promoting economic stabilization. You also point out that the economic collapse and international sanctions have a relationship with Venezuelan migration, which according to UNHCR already reaches the figure of 8 million people. How are sanctions and the economic collapse related to migration?

A: Actually, the link is quite clear. First, there’s the fact that Venezuelan emigration is driven by an economic collapse. Venezuela went from being a country with low net emigration levels to experiencing, during the period of its economic collapse, a 71% loss of its per capita gross domestic product — the largest documented drop in peacetime in any economy in the world. That generated a massive exodus because economic opportunities collapsed.

A recent study by Datanálisis reaffirms this: surveyed Venezuelans say their decision to emigrate is fundamentally an economic decision. In my research, documented in several papers published in peer-reviewed journals, I have shown that sanctions have played a significant role in the Venezuelan economic collapse. They are not the only factor, but they are an important one. In fact, in Chapter 10 of my book Venezuela’s Collapse: Scorched Earth Politics and Economic Decline (Notre Dame Press, 2025), I present estimates that attribute 52% of the Venezuelan economic collapse to the adoption of sanctions and other restrictions on Venezuela’s international insertion, as a result of US foreign policy.

When these two elements come together, it becomes clear — and that is the central argument I have made — that there is a very significant impact of sanctions on migration. Of the approximately eight million people who have emigrated, I estimate that we can attribute around four million to the effect of sanctions.

It is important to point out that it’s not only my research that supports this thesis. There is an established literature showing that sanctions have very significant economic effects on sanctioned countries: they can produce economic collapses comparable in magnitude to the US Great Depression, increases in mortality, and widespread deterioration in living conditions. There is also direct evidence that sanctions affect migration, particularly in a paper by Jerg Gutmann and co-authors, which presents very compelling evidence in that respect.

Unfortunately, a couple of months ago a paper was published arguing the opposite thesis: that a return to a maximum pressure policy would reduce migration, by reviving the hope of regime change. That paper was published by Ricardo Hausmann and Dany Bahar. I say it is unfortunate because it was later shown that their results were based on a methodological error that the authors themselves have already acknowledged, and when that error was corrected, the statistical significance of those results disappeared. I also say it because, despite those results being discredited, the argument continues to be repeated in some circles.

I believe it is important for there to be seriousness and transparency when scientific evidence is used in public debate. And that is why I consider the peer review process, the refereeing, to be fundamental, as it is a guarantee that research-based claims are validated by the academic community. The work by Bahar and Hausmann did not go through that filter.

In any case, to me the issue is clear: if your strategy is to destroy the Venezuelan economy, then Venezuelans will flee a destroyed economy. It is not surprising that the maximum pressure and economic harm strategy has been accompanied by maximum suffering for Venezuelans and by a massive exodus.

Q: In Venezuela, the withdrawal of oil licenses and the application of tariffs on crude will coincide with a deepening of the crisis. At the same time, international financing for humanitarian matters — which already showed a significant deficit — will be further reduced after the Trump Administration’s decisions to cut these expenses. For their part, the European Union and its member states, which are also important contributors in financing humanitarian programs, will see their budgets in this area affected due to the growing need for investment in defense, derived from the war in Ukraine.

On the other hand, the approval of the Law for Oversight, Regulation, Action, and Financing of Non-Profit Social Organizations has been pointed out as a reason for several non-governmental organizations to cease operations in the country, as was the case with Alimenta La Solidaridad a few weeks ago.

How do you view the outlook? Some experts fear a new social collapse. Do you fear that something like that could happen?

A: Rather than talking about a new social collapse, I would talk about the continuation of the social collapse. In reality, in terms of living standards, the recovery that Venezuela experienced between 2020 and 2024 has been very slight. The gap between the income and living levels we had in 2012 and those we have today remains massive. It is true that the lowest point in practically all indicators was 2020, but it is also true that, although there has been a slight recovery, we are not very far from that level.

Yes, I do believe what is happening with humanitarian organizations is very harmful, for the reasons you mention: the fall in international assistance, the deep cuts by the Trump administration, and also the decisions of the Venezuelan government on this issue. Here I would again insist on the need to put this issue at the center of the discussion: how we seek ways so that the political conflict does not contaminate the work of humanitarian organizations.

I condemn in the strongest terms the limitations that the Maduro government is imposing on these organizations, and more generally, the persecution of many of them, which also occurs within a framework of much more generalized and indiscriminate political repression. But we must also remember that the Venezuelan opposition has carried out an enormous politicization of the humanitarian issue. Let us remember that in 2019 it was proposed that there would be a humanitarian intervention, and they tried to organize an alleged entry of aid through the border, with the idea that this initiative would provoke a collapse in military support for Maduro.

Here we return once again to the essential issue: both sides of the political conflict have politicized the humanitarian issue, and those who have paid the cost are Venezuelans. The question, then, is how we can depoliticize the humanitarian issue, so that aid reaches the Venezuelans who so desperately need it.

“I was very critical of the Barbados negotiation, because I cannot understand how it can make sense to center a negotiation solely on presidential elections, when what those elections do is simply determine who will manage absolute power in Venezuela.”

Q: In what way should the international community act regarding the isolation of Venezuela? Can they help in the Venezuelans’ fight for democracy?

A: I believe that the issue of the fight for democracy must be addressed with much moderation, prudence, and frankness. Venezuela today lives under an authoritarian regime, of that I have no doubt, and I believe it must be said clearly. In fact, this issue is so clear that the possibility of me saying it openly depends on the fact that I reside outside the country. If I did not live abroad, my chances of saying it — and who knows if also your chances of publishing it — would be very different.

Now, how does one move from an authoritarian system to a democracy? Within the leadership of the Venezuelan opposition, there are those who propose that it’s by posing a fight to the end against those in power. And I believe that that narrative is what has sunk us further into the authoritarian drift. Because that drift has much to do with the fact that the parties to the conflict see it as existential: their victory is a condition for their existence, and their political project is the annihilation of the other.

Unfortunately, in Venezuela we have two poles of the political conflict that see it that way, that have not been capable of conceiving coexistence. And therefore, it is not surprising that we continue to be trapped in this conflict trap.

I truly don’t know who could think that a transition to democracy is going to be achieved by declaring to the four winds that Maduro and all the Chavistas are going to be thrown in jail. That is not how democratic transitions happen, at least not peaceful ones. And if what is proposed is a non-peaceful exit, I have news for those who think that way: the one who has everything to gain if there is no peaceful outcome is Maduro, because he is the one who holds the monopoly of force.

I don’t pretend to have the answer to how we reach democracy. But I do have the intuition that, if we want to get there, the objective has to be to establish a negotiation — and here I do believe the international community could play an important role — that is not centered on determining who gets to keep power, but on laying the foundations of coexistence.

I was very critical of the Barbados negotiation, because I cannot understand how it can make sense to center a negotiation solely on presidential elections, when what those elections do is simply determine who will manage absolute power in Venezuela. A negotiation centered on the question of who cuts off whose head, of course, is not going to reach a viable agreement.

A different negotiation would be one in which, as a society, we agree on institutions that guarantee that no one cuts off anyone’s head.

I insist that this has a lot to do with reversing the damage that the destructive political conflict has done to our economy, to our society, and to the future of Venezuelans. Because to heal our economy, what we need is an agreement in which the parties accept to stop fighting with scorched-earth strategies, which have done nothing but turn the Venezuelan economy into a battlefield of politics. The central and priority thing is to minimize the damage being done to Venezuelans.

And I believe that the role that not only the international community but all those who want to help Venezuela should play is to promote an understanding around a set of basic rules that protect Venezuelans from the collateral effects of the political conflict. Rules that prevent Venezuelans from continuing to be used as disposable chess pieces in the middle of a power struggle. And that it be understood that our future cannot be built on the ashes of a country set ablaze by those who preach a war without quarter.