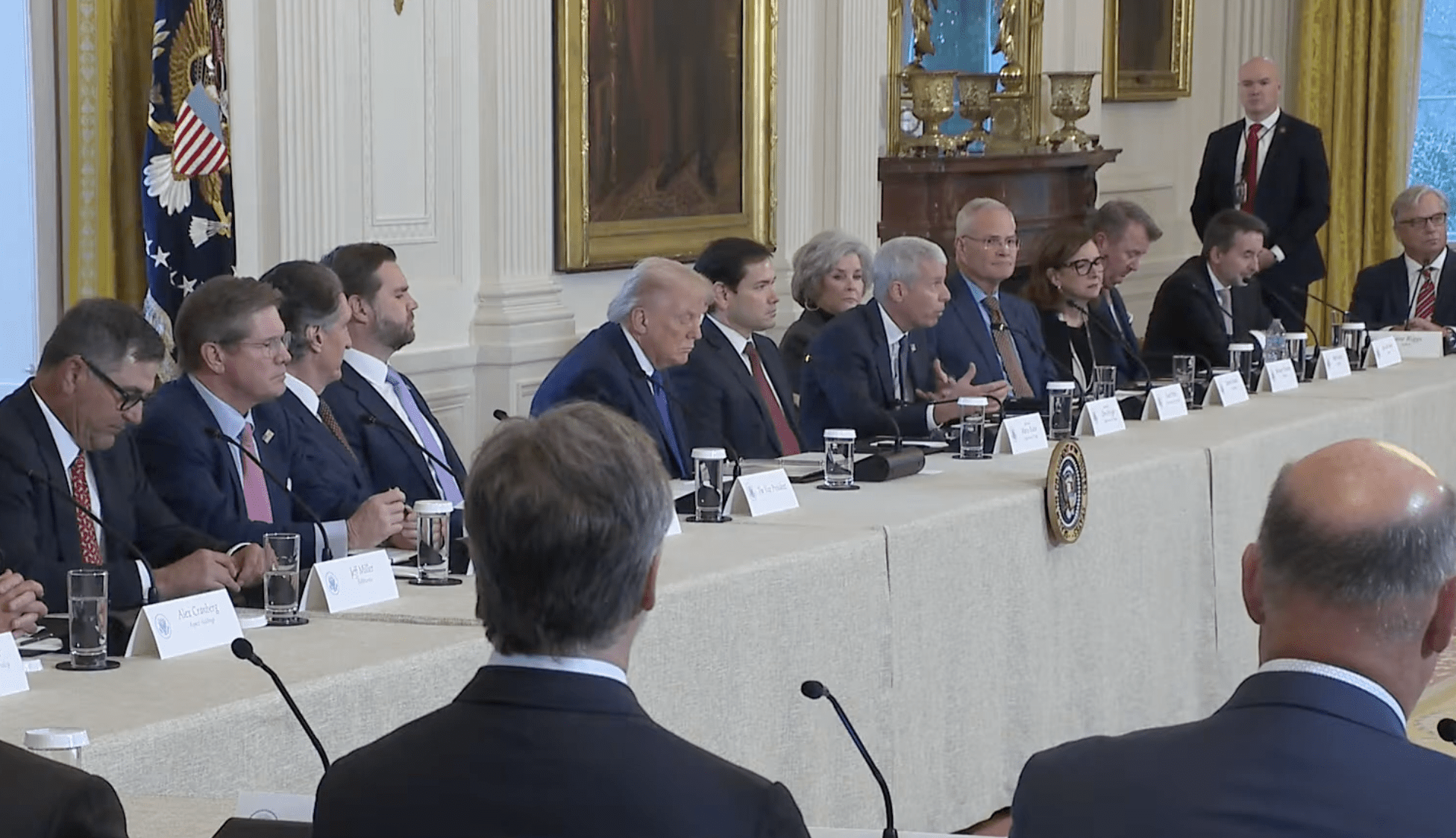

U.S. President Donald Trump, with members of his cabinet, including Vice President JD Vance, Energy Secretary Chris Wright and State Secretary Marco Rubio, along with 17 oil executives. Photo: The White House.

Guacamaya, January 15, 2025. On January 9, U.S. President Donald Trump invited seventeen energy executives to the White House, as he invited them to invest “$100 billion” in Venezuela, a country with some of the largest reserves of oil and gas in the world. But are they heeding the call?

Most business leaders used the opportunity to voice their readiness to enter or, in some cases, re-enter the South American country, and flatter Trump. Others, however, such as ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods, expressed doubts, even arguing Venezuela is “uninvestable” under current conditions. Before the meeting, an anonymous executive told the Financial Times: “No one wants to go in there when a random fucking tweet can change the entire foreign policy of the country”

Just six days prior, Trump ordered a military operation that concluded with the kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, who are now facing trial in New York for drug trafficking charges. Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, now taking over in an interim capacity, has stated that she is open to working with the United States, despite having publicly called for the release of Maduro and Flores. She has held various phone calls with Trump and his administration officials, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

The U.S. president has publicly and repeatedly stated that his main goal in Venezuela is to access and control its vast oil reserves, but he needs American businesses—as well as some tolerated allies—to commit their billions. There is no clear roadmap, however, and that’s behind most of the hesitation.

Will the U.S. Treasury’s Office for Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) lift sanctions on Venezuela’s oil and financial sectors, or create limited exceptions, such as special licenses? Will there be privileges for American businesses over the rest? Will investments have backstops? How will physical security be guaranteed in an unstable country? It is so much so, that a foreign country recently snatched its head of state. Already, the Trump administration is discussing involving private security companies in oil fields.

Last week, the Delcy Rodríguez-led Interim Government of Venezuela announced broad reforms to the economy, including changing laws about mining, foreign trade, industrial property, and the national electrical grid. But codes affecting oil were not mentioned, notably the Hydrocarbons Law of 2006. In recent years, Caracas has been crafting contracts that are more favourable for investors than the standard “joint venture” or empresa mixta model, under the Anti-Blockade Law of 2020. If sanctions were lifted, would that law be reversed?

We are learning of new plans every day. In fact, this is likely because plans are being scrambled on the way, as multiple sources in Washington, DC with information on the matter, have told Guacamaya.

Now, who are the executives and companies that attended Trump’s meeting? What is their attitude towards Venezuelan oil thus far? And who was notably missing?

It could be that Trump’s goal for the meeting was mostly to make a grandiose political show, with oil executives going on camera to thank him for his recent actions, and for opening up Venezuela’s natural resource wealth. Many of the companies present have also been significant donors to his campaigns. But if that was the objective, it has not been achieved, as many still express reservations, to say the least.

The White House event also reflects how wildly different the paths are that Standard Oil’s descendants have taken. For instance, ExxonMobil has, over time, moved its focus towards Guyana, a rival and competitor to Venezuela; ConocoPhillips has been the most aggressive creditor as it tries to collect $12 billion; and Chevron has manoeuvred to not only protect its assets, but also increase its presence.

The exiled giants, reluctant to return: ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips

When Trump was thinking about Big Oil investing in Venezuela, he was probably visualising two names besides Chevron: ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips. But the two have had a rocky history with the governments of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, starting with nationalisations that they deemed as illegitimate expropriations. And they are not so sure about going back, unless they have a clear picture of how Caracas will reform rules for the industry.

ExxonMobil, the largest U.S. oil company—China and Saudi Arabia have the frontrunners for the world. This behemoth has been the most outspoken about not investing in Venezuela under current rules. CEO Darren Woods told Trump that the South American country must change its laws, or it will remain “uninvestable.” This prompted the commander-in-chief to consider leaving out Exxon from his desired “$100 billion” Venezuela oil deal.

The $530 billion giant would probably not be recovering its former assets in the country, but instead would have to invest in new ones. The Cerro Negro field is now the largest joint venture between PDVSA and a Russian state-owned company, producing 95,000 barrels per day as of late 2025.

ExxonMobil has continued to have a strained relationship with Caracas for its protagonist role in the Stabroek offshore oil block. Controlled by Guyana, it is in waters claimed by Venezuela as its own, as it is off the coast of the Essequibo territory. Rex Tillerson, a former Exxon CEO (2006-2016), was also the U.S. Secretary of State from 2017 to 2018, right when the first Trump administration started imposing sectoral sanctions on Venezuela.

ConocoPhillips has probably been the most visible creditor of Venezuela. It has two arbitration awards against Venezuela, for $8.7 billion and £2 billion, which have since grown with accrued interest, turning the company into the largest non-sovereign creditor. Alongside miner Crystallex, they are first in line to be paid off if PDV Holding, the parent company of refiner Citgo, is sold off to satisfy claims.

At the meeting with 17 oil executives, CEO Ryan Lance spoke of recovering its $12 billion debt, although Trump said, “We’re not going to look at what people lost in the past, because that was their fault.” The large debt might make a “good write-off,” a term for companies to recognise losses to lower their taxable income. “It’s already been written off,” Lance responded.

Until 2007, ConocoPhillips was active in the Hamaca and Zuata areas of the Orinoco Oil Belt, which included heavy crude upgraders. The first field is now covered by a PDVSA joint venture with Chevron, now known as Petropiar, while the second has a novel partner, A&B Investments, a company backed by Venezuelan and Brazilian investors, under the Petrororaima joint venture. ConocoPhillips also produced oil in the Corocoro offshore field, which is now operated by PDVSA together with Italy’s Eni.

In 2018, ConocoPhillips struck a deal with the Maduro government to have some of its debts paid off after it seized Venezuelan assets in the Caribbean. In 2019, payments were rendered impossible with sanctions and the U.S. recognition of a so-called “interim government” headed by Juan Guaidó, which would from then on be held accountable for Caracas’s debts.

Sunk costs: Chevron, Repsol, Eni

Three executives represented companies that have been around in Venezuela for decades, and invested such large sums, that they are the most eager to take full advantage of political change on the ground: Chevron, Repsol, and Eni. They know the inner workings of PDVSA and Caracas politicking, and that Trump needs flattery.

Chevron is the largest U.S. company in Venezuela. It has been able to stick around for over a century. When Trump eliminated just about every sanctions waiver in 2025, he created a new special license for this corporation. It’s just too big. In Venezuela, its joint ventures with PDVSA are pumping out 243,000 barrels per day, or 21% of the country total, based on October 2025 figures. Now, Chevron is expected to receive an expanded OFAC license for Venezuela as soon as next week.

Even through the highest points of tension between Trump and Maduro, Chevron-chartered tankers sailed across the Caribbean loaded with Venezuelan crude, bound for the East Coast refineries. For reference, in October 2025, the U.S. energy corporation shipped 135,000 barrels per day, 56% of what it produced between its four joint ventures.

In the meeting with Trump, Vice Chairman Mark Nelson said that Chevron can rapidly increase its production. “We have a path forward here very shortly to be able to increase our liftings from those joint ventures 100% essentially effective immediately. We are also able to increase our production within our own disciplined investment schemes by about 50% just in the next 18 to 24 months.”

The CEO of Spain’s Repsol, Josu Jon Imaz, understood the assignment. He first made sure to mention $21 billion the corporation has invested in the U.S., and then claimed it can quickly boost its output in Venezuela. “Today, we are producing 45,000 barrels of oil a day, gross, and we are ready to multiply by three this figure, in the coming two to three years, investing hard in the country, following your recommendation, if you allow us of course.”

Together, Eni and Repsol are producing about a third of Venezuela’s natural gas consumption by exploiting the Perla field. The Italian energy company has benefited from Trump’s good relations with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni: it remains as the only European firm with a special sanctions waiver.

Vitol, Trafigura: non-U.S. traders allowed to sell to Asian buyers

Representing Vitol, a European commodity trading multinational, was John Addison, a senior executive at the firm; and Richard Holtum spoke on behalf of Singapore-based Trafigura. Both have been involved in shipping Venezuelan oil before the 2019 sanctions, and at later periods under OFAC licenses.

According to Reuters, two traders are already in conversations with refiners in India and China for deliveries in March, implying that they would already have an authorisation from the U.S. Treasury for this new business opportunity. The refiners could include Refiners Indian Oil Corp, Hindustan Petroleum Corp, Reliance Industries, and PetroChina.

In this case, the two leading trading houses would be selling the Venezuelan oil that was filling storage tanks to the brim due to Trump’s recent naval blockade, which resulted in the seizure of five tankers. The proceeds from the sales, estimated at $500 million, are going into bank accounts in Qatar, to be managed by Trump. In a social media post, he claimed that is so they are used in a way “that benefits the people of Venezuela and of the United States.” The U.S. OFAC has authorised for the revenue to reach the Central Bank of Venezuela, which will be able to distribute this hard currency to buy food products.

Sanctions are not the only hurdle in this case. In March last year, Trump introduced “secondary tariffs” of 25% on all trade with any country that were to buy Venezuelan oil and gas. This resulted in companies either cancelling or redirecting shipments. But if India and China—not counting so-called “teapot refineries” are confident enough to buy Venezuelan oil, perhaps they have been told the way is clear.

Don’t forget about the gas

Shell, a British-based energy multinational, was also present. It has previously participated in joint ventures to produce oil in Venezuela, although now it seems that it is only after one project: the offshore gas fields that cut across the maritime border with Trinidad and Tobago.

While Shell and its local partner, the island’s National Gas Company, have a U.S. license to proceed, there might be another political obstacle on the way. Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar has made many belligerent statements against the Venezuelan government, while she offered Trinidad as a base for recent U.S. military operations. As Maduro’s lieutenants take over, they could still hold a grudge.

BP was not in the White House, but it has followed a similar path to its fellow Brit. It is also interested in developing a cross-border offshore natural gas field. Trinidad and Tobago has built an extensive network of infrastructure to process and export this fossil fuel, along with dependent industries like petrochemicals and steel. Without access to its neighbour’s reserves, much of its economy could be rendered obsolete as its own subsoil stash dries up—some have said that this could happen in as little as 10 years, including former prime minister Stuart Young.

Oilfield services also present

Large U.S. oilfield services companies Halliburton and Schlumberger were also present at the reunion. They have a long history in Venezuela, and had sanctions waivers linked to Chevron’s licenses, so that they could maintain limited operations in connection with its joint ventures. The same General License 8 also covered Baker Hughes and Weatherford International, although they were not present.

These firms, alongside local or otherwise non-U.S. counterparts, are more important than we usually think. Usually, large corporations like Chevron and ExxonMobil contract out most or all of their oilfield operations to companies such as Halliburton and Schlumberger.

At the White House meeting, Halliburton CEO Jeff Miller said that he had lived in Venezuela for four years himself, and that his company was “very much interested in returning.” Trump asked him why they had left, and Miller had to awkwardly remind him about 2019 sanctions from his first term, which forced U.S. oil firms to shut down.

The Gulf Coast refiners

The history of Venezuelan oil has, for the most part, centred on a symbiotic relationship, between the oil fields around Lake Maracaibo and the Faja, and the refineries along the U.S. Coast, particularly on the recently renamed “Gulf of America.” These were built to process heavy crude, precisely the type that tankers delivered from Venezuela throughout many decades.

It is thus no surprise that Trump brought in two “downstream” executives: Maryann Mannen representing Marathon, and Lane Riggs for Valero. The latter emerged as the top recipient of Venezuelan oil in the U.S., taking 46% of the total from January 2023 to June 2025. Virtually all shipments were provided by Chevron under General License 41.

It is worth noting that, in that same period, ExxonMobil’s refineries made occasional purchases of Venezuelan petroleum from Chevron, and there are new reports that it could be seeking to ramp up imports, independently of whether the corporation will take part in upstream activities in the South American country.

Oil magnates: “We’re going to Venezuela”

Trump also included a group of oil magnates in the invite. Although they do not necessarily have any experience in Venezuela, they often appear as donors of Trump and the Republican Party. Here we can find Continental Resources’ Harold Hamm, Hilcorp’s Jeff Hildebrand, Aspect Holdings’ Alex Cranberg, Tallgrass’s Matt Sheehy, Armstrong Oil & Gas’s Bill Armstrong, and HKN’s Ross Perot.

Many of them are focused inside the U.S., and some are the poster children of the Shale Revolution. These are probably in for a surprise as they start learning about the local rules of the game. Ross Perot, however, might have some relevant experience, as HKN operates two blocks in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Are we missing someone?

Some faces were missing. Florida-based Harry Sargeant III was not present. While his businesses have been involved, at different points, in producing, trading, and refining Venezuelan oil, there are reports that he facilitated high-level communication between Washington, DC and Caracas.

Sargeant’s Global Oil Management Group has been a prolific trader of asphalt from the South American country, while it was permitted by OFAC licenses between late 2023 and early 2025. It is also connected to North American Blue Energy Partners, which produces around 140,000 barrels per day. Further, Global Oil has invested in Curaçao’s Isla refinery, which was built to process Venezuelan oil—it was previously owned by PDVSA. In January 2024, Sargeant took a group of American “wildcat investors” for a visit to Caracas, to evaluate oil and gas opportunities.

LNG Energy Group, created by Texas billionaire Rod Lewis, had also signed a contract with Venezuela to produce oil in 2024, but it never started production as General License 44 expired that year. No representatives of the company were present at the White House during the January 9 meeting either.

There is a further wide range of companies based in France, India, Argentina, China, Russia, Brazil and other countries with a presence in Venezuela’s oil industry, none of which were at the meeting. Their future under a new Trump deal seems uncertain.

Will there be an effort to privilege American businesses over everyone else? By inviting companies like Repsol, Eni, and Vitol, the U.S. president has signalled that, at the very least, he’s open to friendly, Western nations. But ad hoc is the term of the moment, and the state of relations with Trump personally may be the defining factor. He is now on good terms with President Lula da Silva, despite earlier friction between the two; does that mean Brazilian investors are good to go? Will only sanctioned countries, like Iran and Russia, be left out?