World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Photograph: Web / World Economic Forum

Guacamaya, January 21, 2026. The World Economic Forum returns to Davos from January 19 to 23, 2026, for its 56th edition, in an international context described by the organizers themselves as one of “maximum tension.” Chosen decades ago as the quietest month in the political calendar, January no longer offers respite: latent wars, open strategic rivalries, and a fragmented global economy turn Davos into a setting where dialogue is urgent, but also deeply uncomfortable.

When, in the 1980s, the World Economic Forum sought a date to bring together the world’s leading political and economic actors, the criterion was simple: choose the moment of the year with the least international noise. January seemed ideal. Since then, the small Swiss town of Davos has become the annual meeting point of global power. In 2026, that historical logic is called into question. The meeting is still held in January, but in a world marked by open confrontation and the erosion of the basic consensuses of the international order.

Once again, the Forum is the epicenter of global public attention. Nearly 3,000 participants from 130 countries gather in Davos, including heads of state and government or their representatives, chief executives of major corporations, leaders of multilateral institutions, and members of civil society. All main sessions are broadcast live worldwide, reinforcing the event’s role as a global dialogue platform. Precisely because of this vocation, the 2026 edition has taken on particular symbolic weight.

This year’s chosen theme is “The Spirit of Dialogue,” a slogan that contrasts sharply with the international climate. The central sessions aim to open new avenues of discussion around two axes considered urgent: geopolitics and economic growth. Added to this is a strong emphasis on the profound transformations facing the workforce and the challenge of rebuilding prosperity without exceeding planetary boundaries.

From the World Economic Forum, organizers insist that the dichotomy between environmental protection and economic growth is not inevitable. On the contrary, they stress that resilient ecosystems are a prerequisite for long-term economic and social stability. In this sense, they argue that investing in regenerative, circular, and inclusive systems of production and consumption can ensure that growth remains within planetary limits.

A Davos dominated by geopolitics

The central political figure of this edition is Donald Trump. Following his direct involvement in Venezuelan politics, the President of the United States has generated new international tensions by expressing his desire to move forward on Greenland, straining relations with the European Union. Davos also marks his presence on European soil amid this climate of friction.

Around him, the Forum achieves one of its historic objectives: bringing together, in the same place, actors who rarely share space. Advisors to the governments of Russia and China are present, although it is unknown whether there will be private conversations between them or with Western representatives. This discreet yet inclusive character remains one of Davos’s greatest assets.

Even before arriving in Switzerland, Trump dominated headlines. First, due to the leak of messages from a private chat he held with Emmanuel Macron, President of France, who is also attending the Forum. Then, because of a technical incident during his flight from Washington: the aircraft had to return just 40 minutes after takeoff due to what the White House described as a “minor electrical problem.”

Venezuela at the center of Trump’s discourse

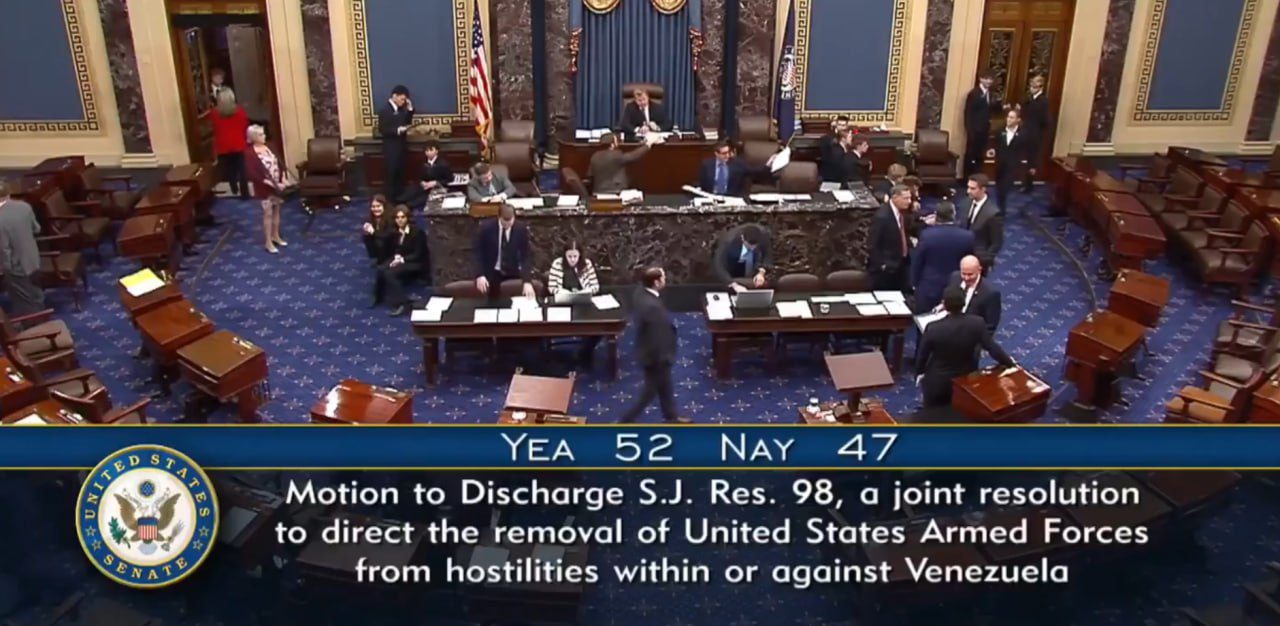

One of the most widely commented statements of the Forum came from Trump himself. Speaking from Davos, he claimed that Venezuela will earn more money in the next six months than in the last 20 years. The U.S. president stated that the country will experience an unprecedented economic rebound thanks to recent oil agreements reached with Washington, following the capture and extraction of Nicolás Maduro. The claim had an immediate impact, both because of its economic content and its political implications.

Mark Carney and the voice of middle powers

Among the most notable interventions at the Forum was that of Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, who offered a structural reflection on the historical moment the international system is experiencing.

“The old order is not coming back. We should not mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy. But from the fracture, we can build something better, stronger, and fairer,” Carney told an attentive audience.

The Canadian head of government focused on the role of middle powers, which he described as the countries that have the most to lose in a world of fortresses, but also the most to gain from genuine cooperation. “The powerful have their power. But we also have something: the ability to stop pretending, to call things by their name, to strengthen our foundations, and to act together,” he said.

Carney went further by openly questioning the traditional narrative of a rules-based international order. “We knew that the story of the rules-based international order was partially false, that the strongest exempted themselves when it suited them, that trade rules were applied asymmetrically, and that international law was enforced with greater or lesser rigor depending on the identity of the accused or the victim,” he noted.

He acknowledged, however, that this “fiction” had practical utility. In particular, he highlighted that U.S. hegemony contributed for decades to providing global public goods: open sea lanes, a stable financial system, collective security, and support for dispute resolution frameworks.

“We are not in the middle of a transition, but of a rupture,” he warned. In his diagnosis, the crises of the last two decades—financial, health, energy, and geopolitical—have exposed the risks of extreme global integration. More recently, he added, major powers have begun to use economic integration as a weapon: tariffs as leverage, financial infrastructure as coercion, and supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited.

“One cannot live in the lie of mutual benefit through integration when integration becomes the source of your subordination,” he concluded.

Emmanuel Macron: defense of multilateralism and european sovereignty

In response to Trump’s policies and rhetoric, French President Emmanuel Macron delivered a forceful speech against what he described as an attempt to subordinate Europe through tariffs and commercial pressure, particularly in the context of the dispute over Greenland.

Macron stressed that “with Greenland, we have threatened no one; we have supported an ally, Denmark,” defending respect for territorial sovereignty against U.S. positions.

He also urged Europeans not to be intimidated by threats or to yield to the “law of the strongest,” calling for the defense of the values and principles that have underpinned the multilateral international order.

His intervention was interpreted by several media outlets as a call for the European Union to strengthen its strategic autonomy and deepen cooperation in the face of policies that could weaken it.

Global risks and a turbulent future

In the days leading up to the Forum, organizers presented the Global Risks Report 2026, based on a survey of 1,300 participants. The report defines the current moment as the entry into an “era of competition,” marked by fragmentation and confrontation.

The outlook for the coming years is described as “stormy” or “turbulent.” Geopolitical risks are identified as the main source of instability in the short and medium term, while environmental threats are considered the greatest long-term risk.

Davos, between dialogue and fracture

As international coverage has highlighted, Davos 2026 is not only an economic summit. It is a thermometer of the state of the world. The convergence of speeches announcing deep ruptures, promises of accelerated growth in politically volatile contexts, and calls to rebuild cooperation on new foundations reveals a Forum permeated by tensions.

January is no longer the month of calm. But Davos remains, at least for a few days, the place where everyone—rivals included—sits at the same table to try to understand where an international order is heading that, as Mark Carney warned, can no longer pretend to remain intact.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) was founded in 1971 by Klaus M. Schwab, a professor of business policy at the University of Geneva, with the aim of creating a space where business executives could exchange management practices and strategic vision.

Initially called the European Management Forum, the event first held in Davos brought together business leaders from Western Europe. However, faced with the global challenges of the 1970s—including economic and geopolitical crises—the Davos agenda quickly expanded to include economic, social, and political issues, inviting political leaders for the first time in 1974.

In 1987, it adopted its current name, World Economic Forum, with an explicit focus on providing a platform for international conflict resolution and cross-sector cooperation. Since then, Davos has been the stage for unusual diplomatic encounters—such as rapprochements between Greece and Turkey or between Nelson Mandela and Frederik de Klerk in South Africa—and for a growing number of initiatives on global health, sustainability, and economic transformation.

Throughout its history, the WEF has sought to position itself as a space for dialogue between the public and private sectors to address global challenges, although it has also been criticized for its elitist character and its real impact on global politics.

Venezuela’s presence at the World Economic Forum has not been constant, but it has had symbolically important moments.

For example, in 2014 Venezuela was represented at the Forum’s Annual Meeting by civil society actors.

Venezuela returned to Davos in 2020 after 28 years, with the presence of figures such as Juan Guaidó, President of the National Assembly, who in one of those interventions called for strengthening international aid to address the country’s political and social crisis.

Davos 2026 exposes a Forum that continues to believe in the usefulness of global dialogue, but that faces a reality of deep tensions among its participants. The interventions of Trump, Macron, and Carney not only represent divergent positions, but also reflect a global crossroads over how to articulate cooperation in a fragmented world.

While the Forum proclaims “the spirit of dialogue,” the statements of leaders—from tariffs and sovereignty to economic rebounds—show that this spirit is being tested as never before in recent decades.