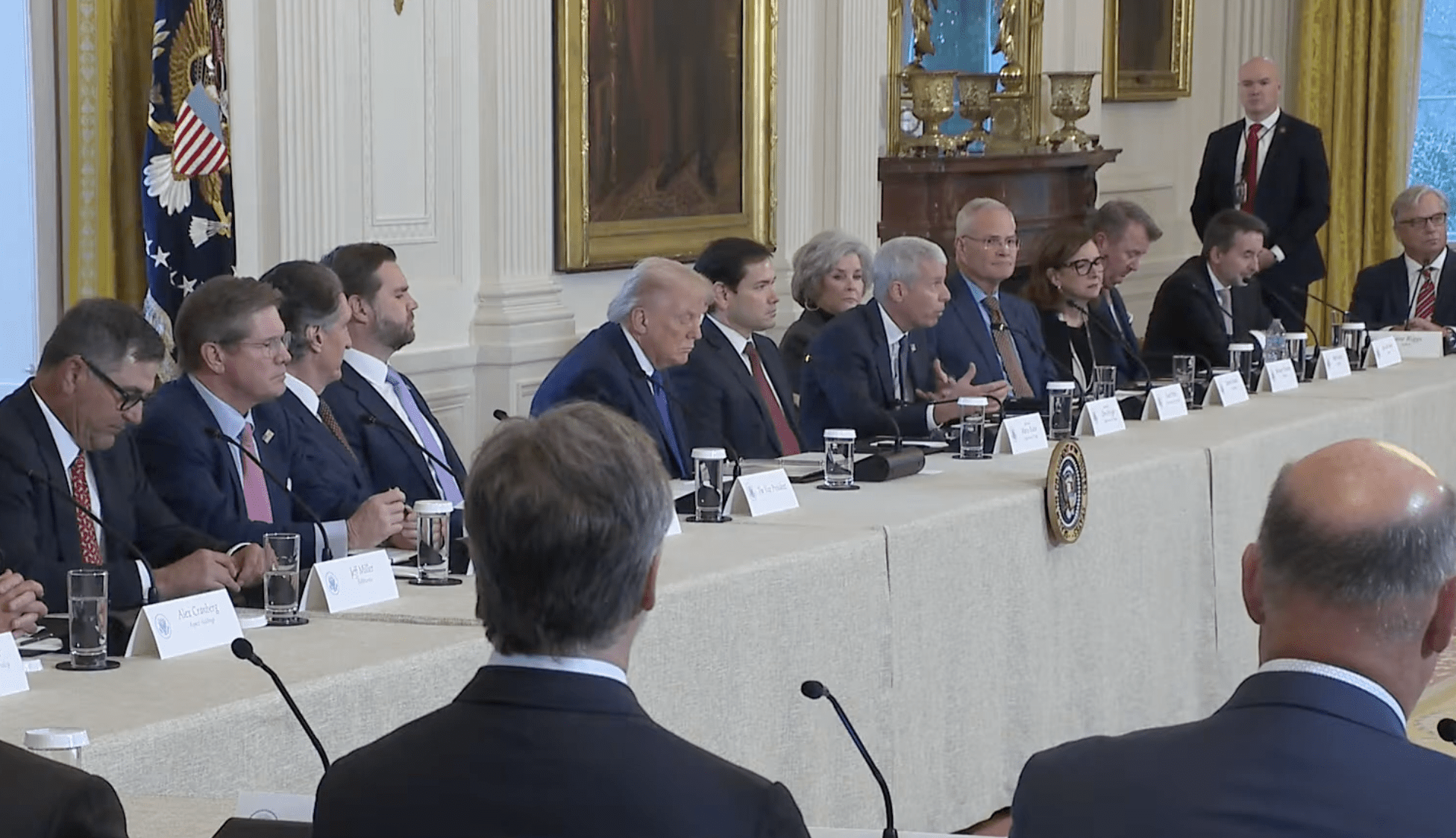

Eric Ondarroa is running for governor of Miranda for the Alianza del Lápiz party. He begins a campaign tour in the El Plan de las Praderas neighborhood of Petare, known as the largest “barrio” in Latin America. Photographs: Guacamaya / Elías Ferrer.

Guacamaya, May 19, 2025. The afternoon falls over Petare, and the cool weather accompanies the movement of a typical Saturday in the El Plan de Las Praderas sector. There, amid the noise of children playing in the street and the activity of merchants, Carla and her daughter’s story repeats in hundreds of homes: the little girl, a fifth-grade student in a public school, has gone two months without attending classes.

The girl’s teacher has not been able to return because her husband is sick, and she, like many educators, must choose between her vocation and family emergencies. “Here, sometimes there’s school, sometimes there isn’t. They send my daughter assignments through WhatsApp,” says Carla, resigned but hopeful that something will change. Like this girl, there are many similar stories of children and young people who only attend classes sporadically.

At that hour, just after five, Eric Ondarroa, candidate for governor of Miranda with Alianza del Lápiz, hands a soccer ball to a group of ten children who have improvised a field in the street. With this simple but symbolic gesture, he marks the beginning of a day that will take him, well into the night, through the sectors of Grupo Escolar, El Hueco, La Amapola, and La Barraca.

His main message is in favor of education. “Today, teachers earning two dollars a month cannot possibly come to teach. It’s not that they don’t want to go to the school, it’s that they have no way to get there. That’s why the schedule is a patchwork—in public schools, classes are held two days a week,” he denounces. “We’re stuck in this cycle every day. What do we want? To put our heart into education,” he adds.

Question: You have insisted that education is the main form of wealth in Miranda and Venezuela. What would be your first concrete actions to dignify teachers and improve educational quality in the state, considering the infrastructure crisis and low salaries you yourself have denounced?

Answer: The first thing we will do in Miranda is review the payroll of teachers assigned to the Governor’s Office, so we can give them better conditions, because that is something we can perfectly do through the Governor’s Office, regardless of whether they are paid through the Patria system.

The second thing we will do is take inventory and conduct inspections. I will appoint teams responsible for visiting all schools under the Miranda Governor’s Office initially. Those are the first ones we will put our heart into, in terms of infrastructure and review. We’ll check the kitchens to ensure we can have a School Meal Program that actually works.

Third, the TransMiranda. One thing I want to do with the TransMiranda—and this applies to teachers whether they’re assigned to the Governor’s Office or not—is create school routes with the TransMiranda. This way, we can use the buses to transport kids from one point to another for school, but also, with the TransMiranda, you could have an app to know the routes. By showing your ID or something identifying you as a teacher, it could take you from one point to another on our routes.

My goal is to get hands-on with education. Education doesn’t just mean teachers—we often only talk about teachers, but we also need to put our heart into the administrative staff and school workers, because they make the entire educational process function. I’m very clear on that from an educational standpoint.

I will meet with the Minister of Education, who was also governor of Miranda. Once I’m governor, I will call a meeting with all 21 mayors in my office so we can assess municipal and national schools. Together with the private and public sectors, we will start putting our heart into all schools, regardless of whether they are municipal, state, or national.

Ondarroa walks through the streets greeting neighbors and small business owners who operate out of their homes. Many residents avoid the campaign team’s cameras for fear of workplace retaliation, as they work in the public sector. In Petare, stories of resilience abound. That’s why Ondarroa repeats insistently: “The place where you’re born shouldn’t define your future.”

The absence of teachers, fragmented schedules, and deficits in school meal programs have led families to turn their homes into makeshift classrooms so children don’t fall behind. Ondarroa warns that under these conditions, the quality of learning has plummeted. “They hand them a diploma, but they leave without knowing how to read or multiply,” he denounces.

“If we want to glimpse the Venezuela of tomorrow, we must look at today’s schools,” Ondarroa quotes Arturo Uslar Pietri, convinced that education is the only way to break the cycle of poverty and violence. “We have been dominated more by ignorance than by force,” he adds, echoing Simón Bolívar’s words. His speech rests on these pillars.

Q: You are running for governor without having held elected office before. Why do you believe your experience as a social leader and lawyer prepares you to manage Miranda in such a complex context?

A: I am the most qualified candidate in Miranda today—no doubt about that. I trained for many years in the public administration of what was the best municipality in the country, Chacao, where I held various high-level positions. I was a successful professional in that sense, with over 14 years of experience in the municipality.

I was also the director and founder of a highly successful social program, La Casa del Lápiz, where more than 40,000 Venezuelans have benefited and now have a trade that allows them to live with dignity and earn money in dollars.

Additionally, I come from political schools where the philosophy was work, work, and more work. I had the opportunity to work with Enrique Mendoza, the best governor in Miranda’s history—the Enrique who delivered, the Enrique who was supportive, the Enrique who stood with the people of Miranda. I also had the chance to work with Enrique Salas Römer, one of the best governors in Carabobo’s history.

For over 25 years, I’ve worked with Antonio Ecarri, who was my Tax Law professor at Santa María University and is now the national president of our organization. From him, I’ve learned that no one is better than others unless they work harder than others. We are a team with solid values, principles, and convictions.

We don’t sell out—we’ve always been authentic independents because we have a policy, and our policy is to depolarize the country.

Now, I am a governor candidate with a very clear objective. I come to revive industrial zones and work hand in hand with the private sector because that’s the only way to generate jobs for people in all my working-class sectors who currently have no employment, including our grandparents, people aged 42 to 68.

Additionally, I believe in education. I don’t just talk about education—I will put my heart into education in Miranda. I will also be the governor who guarantees stability in Miranda’s most working-class neighborhoods so the country can breathe, so we can all move forward regardless of political color. I believe in respecting human dignity, and I believe in forgiveness. That doesn’t mean I won’t speak the truth firmly when needed.

Q: You’ve said you’re not coming to govern but to “manage Miranda.” How does that vision translate into practice? What fundamental changes do you propose in regional public administration compared to previous models?

A: I don’t see it as a relationship where there’s a ruler and subjects. I am a manager, and I prepared not only in public administration but also in the private sector—because I don’t live off politics, I live off my businesses and companies. So, what Miranda needs is to identify problems, identify bottlenecks, and establish managerial mechanisms and solutions to resolve them.

I come to unite regardless of political colors, and as an independent and a manager, I won’t hesitate to sit down with those in power at the national level or mayors of any color to ensure water arrives, children eat, and the TransMiranda with school routes exists.

The Marín industrial zone in Cúa, for example, could generate many jobs and attract foreign investment. I will be the governor who steps up to guarantee legal security, stability, and opportunities—because that’s what must be done in all of Miranda’s industrial zones. That requires a manager.

How will I solve the issue of jobs and work opportunities? With the private sector, which has the expertise to make businesses productive, feed people, and employ them. So, it’s a completely different vision. I’m not a petty politician—I don’t believe in politicking. I believe in a coherent and efficient message.

The candidate insists his project goes beyond slogans: “We want schools that teach how to live and work, we want to teach trades. We want children to eat so they can learn. Our goal is to prevent guns on hips and girls having babies,” he states. For him, stability will only come by dignifying people and avoiding social conflict to attract investment.

In this same vein, the tour continues as Ondarroa greets entrepreneurs and small business owners. “This is a different kind of campaign—I believe in the free market. We must end the dynamic of protecting thieves and persecuting workers. I want to generate stability from working-class sectors. Stability can be built from Petare and attract private investment,” he emphasizes.

Q: You’ve pointed out that many of Miranda’s industrial zones are now “warehouse graveyards.” What specific incentives or policies do you propose to reactivate industry and generate jobs in these regions?

A: We have industrial zones in Santa Teresa, Ocumare, Charallave, a few in Santa Lucía, and also in Cúa, where we have the strongest. We also have industrial zones in Guarenas, Guatire, and Altos Mirandinos among the most dynamic. What do I want to do? Attract investment.

I want to promote fiscal incentives and benefits alongside mayors and in talks with the National Public Power. I propose zero taxes for 15 to 24 months, creating a scale with experts based on the number of jobs to be generated. The condition is hiring people living in that municipal quadrant, with a quota for those aged 42 to 68.

I will personally meet with mayors to discuss motivating and incentivizing ordinance modifications in each municipality—of course, laws dependent on the Legislative Council—but I’ll go with a team from the Legislative Council and National Assembly to push these laws in Parliament. Why? To lower taxes.

Today, we have a clumsy tax policy suffocating merchants, entrepreneurs, business owners, and industrialists. I’ve already met with important chambers in Miranda to identify their main problems and build solutions together. I believe in working hand in hand.

That’s why, for me, they’re not adversaries—they’re allies. To make this work, I’ll be the governor who generates social stability and social investment in working-class sectors like Petare, because that’s the only way to also guarantee security for businesses and their infrastructure.

What role would tourism, particularly creating a tourist zone and coastal strip in Barlovento, play in your regional economic development strategy?

I dream of making Miranda compete—in the good sense—with Vargas. I won’t hesitate to recognize good initiatives regardless of political color. When I look at La Guaira, you see a vibrant coastal strip. I want to build one in Barlovento to compete with La Guaira’s—healthy competition.

Barlovento has such a vibrant tradition, so much culture and identity, that we can organize comprehensive tourist routes. I don’t see tourism in isolation—I see it holistically, so that with these coastal strips, I can reactivate the economy. Reviving tourism will immediately reactivate lodging, gastronomy, and services.

Just as Russian tourists go to Margarita, I want to see Spanish, Russian, and German tourists visiting Miranda’s and Barlovento’s coasts—but not just Barlovento. We have an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity: the Dancing Devils of Yare. We forget we have that in Valles del Tuy, and I want us to showcase it.

Amid jokes, Ondarroa points out the number of “Malibús” in this Caracas neighborhood. “All the Malibús in Caracas are in Petare,” he exaggerates. The old car models serve as shared taxis in these sectors, and the candidate celebrates the people’s ingenuity in solving mobility issues—another demonstration of Petare’s unique character.

During his tour, he insists: “We’re running against Capriles’ candidate and Maduro’s candidate because, to us, they’re the same. We need to reset the political board. I’m asking for the chance to build something new.” An elderly woman, recognized for her local leadership, receives Eric’s visit and says: “The only thing I can tell you is that my health is failing, but I won’t stop encouraging people to vote.”

Q: The opposition arrives at these elections deeply fragmented, with some sectors calling for abstention and others betting on participation. How do you assess the strategy of those like María Corina Machado, who urge people not to vote, considering the process fraudulent? What risks and opportunities do you see in each stance?

A: I believe every election is an opportunity to refresh and renew the political board. I have a personal political objective: to reset Miranda’s political landscape with new faces, new actors, and new ways of doing things.

We are a new option for Mirandinos, but one backed by experience—over 21 years in social work, more than 10 in public administration, and deep roots in working-class areas. We come from a school that taught us to do the job right.

I respect those who think differently because I believe in pluralism, freedom of thought, and democracy. I dream of a Venezuela where thinking differently doesn’t make us enemies or traitors. That’s what we’re fighting for. I want to reclaim voting as a lawful right, and I believe in change through the law.

I’m convinced those in power today have lost the streets. The current governor—the one we’re competing against—has no real connection to the people. And I’m also convinced that, starting May 26, we will be the first option to govern Miranda. I have no doubt.

Q: Regarding opposition options, has your political representation attempted to build bridges or alliances with other leaders in Miranda to avoid vote-splitting and strengthen a real alternative to the ruling party?

No, and I don’t want to. We are authentically independent leaders. I respect those running with their own political options, but today, the real, genuine independent choice in Miranda is us. That’s why we’re only running with one political organization: El Lápiz, an independent group.

Other coalitions exist, but I won’t fall for blackmail. My goal isn’t to collect political endorsements—it’s to unite the true grassroots leaders forgotten in every corner of Miranda. Electoral processes across the country have proven it’s not about stacking endorsements; it’s about leadership.

Votes come when you’re on the ground with a message that resonates. We have the drive, the knowledge, and a message that’s gaining traction—you can see it here. There’s no rejection of us. We don’t yet have the recognition we’d like, but today, we’re the leading option.

In the streets, people listen and question. José Luis, a resident of La Barraca, confronts him about vote defense: “How will you protect the results? If you win, they won’t let you govern—they’ll appoint a ‘protector’ over you.”

Ondarroa replies without hesitation: “Let them appoint two protectors. We must always vote to build a popular majority. What happened after July 28 is the consequence of a political leadership that lost the streets.”

Q: On May 25, regional and legislative elections will be held under a National Electoral Council (CNE) whose impartiality has been questioned, especially after last July’s presidential controversies. What guarantees do you and your team have that votes will be respected and results will reflect the people’s will?

A: Our first guarantee is that we’ve been covering Popular Miranda and Deep Miranda. We’ve run a campaign built on organizing people—in Barlovento, Valles del Tuy, Guarenas-Guatire, Altos Mirandinos, and now here in Petare.

You’re seeing us walk through Petare’s most neglected areas, where no politicians go. The truth is, people want real change, and that hope hasn’t faded. Are there wounds? Yes. But there’s also fierce determination.

What are we doing? Identifying and engaging true grassroots leaders—the ones helping us build our witness network. Obviously, conditions aren’t ideal, and impartiality doesn’t exist. Those in power abuse state resources for campaigning.

We’re here humbly, with ideas. We don’t have the money others do, but we have conviction—and we’re where they lost the streets. You can mask your eyes, but not your gaze.

I believe the people will make themselves heard again. Will there be abstention? Yes. But among those who mobilize, many will vote for us—the freshest, most genuine option.

Q: Post-presidential elections, repression and mass arrests fueled distrust. How do you assess the current political climate, and what’s your message to those afraid to participate due to fear of retaliation?

A: We’ve been clear: El Lápiz fought for the freedom of those detained just for expressing their views. We dream of a Venezuela where everyone can exercise political rights without fear of imprisonment for dissent.

That repressive attitude is backfiring. Why? Because this people doesn’t lose hope and rejects oppression. The more you repress and mistreat them, the more they’ll say, “We don’t like this life—we want change.”

Yes, we’ve faced hard times. But I see grassroots bases rebuilding. In the poorest areas, voting is their only peaceful, constitutional option. The working-class Venezuelan won’t surrender a right they fought hard to win.

I’m convinced working-class communities will reject backdoor constitutional reforms. They’ll make themselves heard. Abstention may rise in middle-class areas, but not in working-class zones.

Q: This election has seen technical irregularities, like the removal of QR codes from vote tally sheets. How will your campaign safeguard votes and defend results?

A: QR codes don’t matter to me. What matters is having well-trained witnesses at every table, demanding their copies of the tally sheets.

As a candidate, I’ll demand respect for the tradition of delivering tally sheets—not just to the backup envelope and Plan República, not just to the table chief, but to the top three vote-getters.

If you have your tallies and a mobilized majority, there’s no excuse for disregarding results. Our machinery is ready—and it’s a people’s machinery. You can see it’s rooted in working-class sectors. And you don’t mess with the working class.

On every corner, Petare’s community—marked by scarce services and lack of opportunity, but also unshakable solidarity—receives his message with skepticism but also debate. “We’ll make Petare and Miranda rise,” Ondarroa promises as night falls, his collected stories challenging politics to truly rise to its people’s level.

Q: Finally, how do you envision Miranda in 2029 if you succeed in realizing your project? What key indicators would measure your success as governor?

A: We’ll have a Miranda where, in sports, athletes will win National Games, and we’ll have Olympians coming from Miranda. I dream of a Miranda with sports facilities that aren’t just infrastructure but also academies—because I’m a product of sports too, and I know the values they instill.

I dream of an educated Miranda by 2029, where we can say our children are eating, attending class five days a week, where teachers are the best-paid professionals, and Miranda’s children have taken a PISA test.

I dream of a tourist-friendly Miranda, an educating Miranda, and I’m convinced we’ll find a Miranda where you can walk through Petare without fear. People will come, just like they do now in San Agustín, where some are doing tours—I’ll make that happen here in Petare.