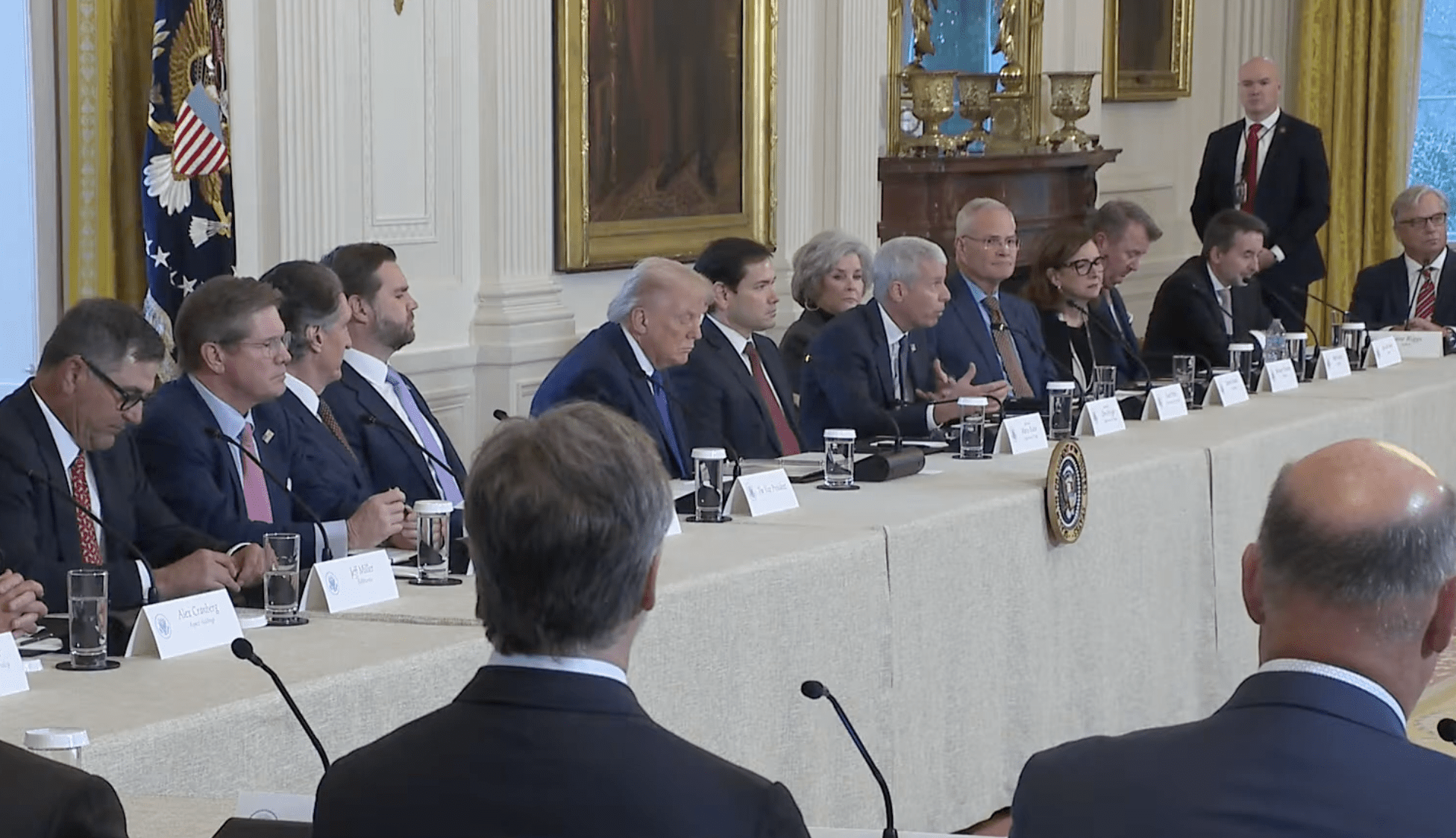

Incumbent President Irfaan Ali is widely expected to win the general elections in Guyana again on September 1. Photo: Office of the President (Guyana).

Guacamaya, August 29, 2025. Guyana is heading towards the general elections on September 1, 2025, in a climate of high internal and regional tension. Having become an emerging oil power, Guyana is voting under the weight of the dispute over the Essequibo with Venezuela, the influence of major oil companies, and the watchful eye of military partners like the United States and the United Kingdom. The outcome will determine not only local governance but also hemispheric energy security and the geopolitical balance in the Caribbean.

How do elections work in Guyana?

General elections are being held in Guyana on September 1, 2025, to elect the 65 seats of the National Assembly and, simultaneously, the President. This early election is a result of the dissolution of parliament by President Irfaan Ali on July 3, 2025.

The National Assembly follows a system of proportional representation with closed lists, featuring 40 seats in a national constituency and 25 distributed across 10 sub-national constituencies, allocated by the Hare quota. At the same time, the head of state is elected by a simultaneous two-tier vote where each list includes its presidential candidate.

The background of the 2020 elections indicates that the PPP/C returned to power with 33 seats and 50.69% of the votes; the APNU alliance with the AFC obtained 31 seats with 47.34%; and the LJP–ANUG–TNM alliance won 1 seat with 1.13%. The count was delayed by four months due to attempted manipulation in favor of the then-ruling coalition.

While Guyana has about 850,000 inhabitants according to the census, 750,000 are called to vote in a single round that will crown the winning party’s candidate as president.

The Candidates

Ethnic and partisan segmentation persists in Guyana, with traditional Indo-Guyanese support for the PPP/C and Afro-Guyanese support for the PNCR/APNU. However, the oil boom and the security agenda could reshape preferences.

The ruling party (PPP/C) is repeating its ticket with Irfaan Ali and Mark Phillips. General Secretary Bharrat Jagdeo highlights the government’s work and management of the oil boom. Their message is: sovereignty, national security, and continuity of growth.

The opposition (APNU) is running Aubrey Norton (leader of the PNCR) with Juretha Fernandes as his running mate. They propose transparency, a “patriotic front” against what they consider threats to territorial integrity, and a more equitable distribution of revenues.

In a sort of third way (WIN), we have businessman Azruddin Mohamed, who seeks to break the two-party system. He amassed a large fortune in gold mining and faces U.S. sanctions for tax evasion. He was labeled a “puppet candidate for Maduro” by a U.S. congressman; Mohamed denies this and accuses the government of hiring lobbyists in Washington to damage him.

Electoral Alliances:

- On May 30, APNU sealed an alliance with The Working People’s Alliance (WPA).

- On June 29, WIN agreed with ANUG to merge under Mohamed’s logo and candidacy (ANUG retains its legal personality).

- On July 1, Forward Guyana was born when The People’s Movement and the Vigilant Political Action Committee created the Forward Guyana Movement as a unified list.

An Oil Economy with High Social Expectations

From being one of the poorest countries in the region, Guyana is experiencing explosive economic growth since the discovery and development of oil reserves off its coast.

With the discovery of the Stabroek block, holding 11 billion barrels, Guyana has the highest proportion of barrels per inhabitant, both in reserves and production. The country began oil extraction in 2019, reaching 650,000 barrels per day this year. It is projected to reach 1 million barrels per day by 2030.

The country’s GDP has grown at double-digit rates since 2020, reaching 63% in 2022 and 43.6% in 2024, the highest rate in the region. It already has the highest GDP per capita in South America: $32,300, which would be 8 times that of Venezuela, according to the IMF.

In Guyana, what many experts call the paradox of abundance exists, as despite the boom, social and infrastructure deficiencies persist. The central debate is how to transform revenue into sustainable well-being with clear rules, sovereign funds, and transparency.

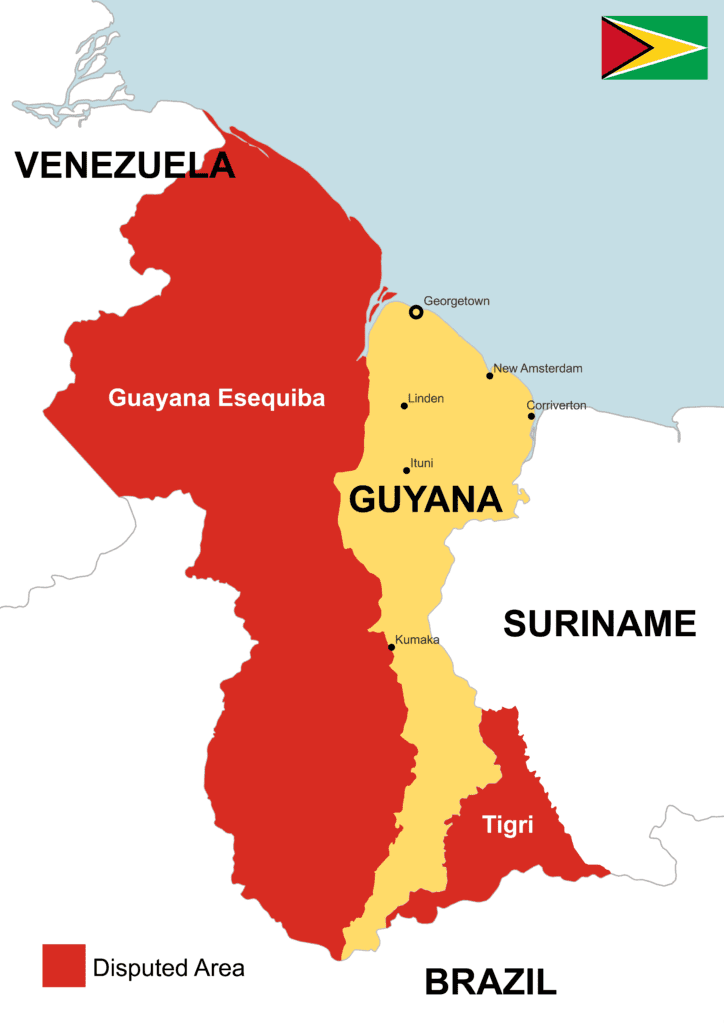

The Essequibo: A Campaign Issue

To understand the importance of this issue, it is pertinent to review the historical context of the Venezuelan claim: it asserts that the Essequibo was part of the Captaincy General of Venezuela and that the Paris Arbitral Award (1899)—which granted the territory to British Guiana—was null and fraudulent, tainted by pressure and agreements between powers. The Geneva Agreement (1966), signed with the United Kingdom and the newly independent Guyana, explicitly recognizes the dispute and mandates seeking a mutually acceptable solution.

From Caracas, it is argued that mining and oil concessions in the disputed area alter the status quo, contravene the spirit of the Geneva Agreement, and improperly condition the negotiation. The offshore expansion linked to the Stabroek block is seen as a paradigmatic case.

A precedent rarely mentioned in the international press when discussing this issue is the silenced Rupununi Rebellion of 1969.

In January 1969, Amerindian communities and cattle ranchers from the Rupununi region, located south of the Essequibo, rose up against Georgetown due to neglect and lack of rights, expressing affinity with Venezuela. The rebellion was quickly suppressed with violence and external logistical support; many leaders fled to Venezuelan territory, where they received refuge.

For Venezuela, this episode shows that part of the population has not fully identified with the Guyanese state and reinforces the thesis that the Essequibo is not a territory consolidated under Georgetown’s control, but rather an area with cultural, geographical, and political ties closer to Venezuela.

Oil Companies with Interests in both Venezuela and Guyana

Interestingly, several energy companies maintain a presence or have interests on both sides of the dispute over the territory of the Essequibo.

ExxonMobil (USA): In Guyana, it is the lead operator of the Stabroek block. In Venezuela, it has a history of litigation and friction over expropriations and concessions in the maritime area linked to the Essequibo. The Venezuelan government has accused the company of “funding the opposition” and “promoting sanctions against Venezuelan oil.”

CNOOC (China): In Guyana, it is a partner in the Stabroek consortium with Exxon. In Venezuela, companies from the People’s Republic of China are strategic partners in upstream and refining projects, key to Beijing’s energy diversification.

Chevron (USA): In Guyana, the company holds a 30% stake in Stabroek after acquiring Hess Corporation. The operation, challenged by ExxonMobil, was cleared by a favorable ruling from the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). In Venezuela, it is the only US oil company with OFAC licenses to extract and export crude under the sanctions regime; it acts as a hinge between Caracas and Washington.

Repsol (Spain): In Guyana, it has a presence through Repsol Exploration Guyana and operates the offshore Kanuku block. Wells like Beebei-Potaro have been commercially disappointing, but the company maintains exploratory activity. In Venezuela, it has been a relevant partner of PDVSA. It obtained special permits during the Biden administration that were tightened under Trump. With support from the Spanish government, it seeks to resume marketing Venezuelan crude shortly.

Spain seeks to diversify its energy supply due to constant tensions with Morocco and Algeria following its change in official position regarding Western Sahara, in addition to the effects of the war in Ukraine. Therefore, Venezuela and Guyana seem like viable alternatives as they are not in high-tension zones like the Middle East. However, this view might be compromised by the tensions in the Essequibo.

Guyana’s Military Agreements

Guyana has strengthened its defense architecture with key agreements, especially with the US and the UK, to deter risks in its EEZ and reinforce interoperability:

United States:

- Shiprider Agreement (2020): Joint maritime/air patrols against illegal fishing, trafficking, and other threats.

- Acquisition & Cross-Servicing Agreement – ACSA (2021): Reciprocal logistics (supplies, maintenance, services) between the GDF and the Department of Defense.

- Regular combined exercises (coast guard and US Navy), exchange of ISR capabilities, and training. Public messages of support for Guyana’s territorial integrity.

United Kingdom: Naval deployments and exercises (including the HMS Trent) as a deterrent and supportive signal. Cooperation in training and maritime awareness.

Brazil: It has also been working and increasing its cooperation with Guyana in the military field and has proposed building a highway to Georgetown to achieve its long-desired access to the Caribbean.

The Venezuelan Position: Caracas denounces the militarization of the dispute and extra-regional support for Georgetown. In parallel, Russia has criticized Western military involvement and deepened its cooperation with Venezuela, recalling precedents of mutual recognition in territorial disputes like Abkhazia and South Ossetia in the 2008 Georgia war. Russian companies like Rosneft also obtained concessions from Venezuela in the past and have had interests in the waters offered by the Essequibo’s maritime territory.

Election Observers

The OAS signed an agreement in July for the deployment of an EOM (Electoral Observation Mission) to accompany the September 1 elections; its constructive nature (positive recommendations for institutions and public confidence) is emphasized.

The European Union mission is led by Robert Biedroń; teams include electoral specialists and long-term observers for comprehensive coverage of the process and its legal-administrative framework.

Given all of the above, it could be said that this is a pivotal election. Guyana is deciding between continuity with the PPP/C, a change with APNU, or disruption with WIN; whoever wins will have to manage the oil boom under high geopolitical pressures from the energy demand generated by global uncertainty in the Middle East and the war in Ukraine.

Oil and geopolitics will be decisive in the coming cycle, marked by investments in Stabroek and adjacent areas involving ExxonMobil, Chevron, CNOOC, and Repsol, which condition the stability of the Caribbean and the energy transition of major powers.

The Financial Times described the situation in Guyana as the construction of the world’s last petrostate at a time marked by significant conflicts. The neighboring country faces notable dependence on the United States and particularly on the ExxonMobil corporation, which seems to be shaping its own project within the goal of turning Guyana into a reliable energy supply partner for the United States. Meanwhile, the Essequibo remains a wound left by British colonialism, whose understanding in the West seems dictated by Venezuela’s current circumstances rather than a broader history that appears to be consciously omitted by various governments and the international press.