Venezuela has the largest gas reserves in Latin America, but no capacity to export. Today, it has a historic opportunity to develop the sector and thus strengthen integration with its neighbors through gas pipelines.

Guacamaya, October 13, 2025. Gas in has never been a priority for Venezuela. The largest proven oil reserves on the planet have overshadowed the vast wealth of the country’s other resources, so we often ignore that it has 221 trillion cubic feet beneath its soil.

Although Venezuela has generally been self-sufficient with its gas, it has had to import it at times. The state has never focused its main efforts on capturing the associated gas or on developing large fields of free gas, preferring to focus on “black gold,” which generates greater profitability for its coffers. But gas must be thought of not only as an economic resource, but also as a tool for regional integration.

In Russia and China, they have learned the importance of the “hard connectivity” that pipelines build, which differs fundamentally from the “soft connectivity” of the maritime oil trade. Therein lies the key, which would make Venezuela an indispensable country for its region.

Now, Venezuela faces two challenges. First, how to build the infrastructure to connect with its neighbours, who undoubtedly need its gas. And second, how to capture the gas that is already being produced, but is wasted as it is vented and flared.

All this under unilateral sanctions from the United States, which affect its ability to obtain financing. The solution lies in enabling a national gas market to encourage private investment, which would already be possible under the existing legal framework.

The need for Venezuelan gas in its neighbours

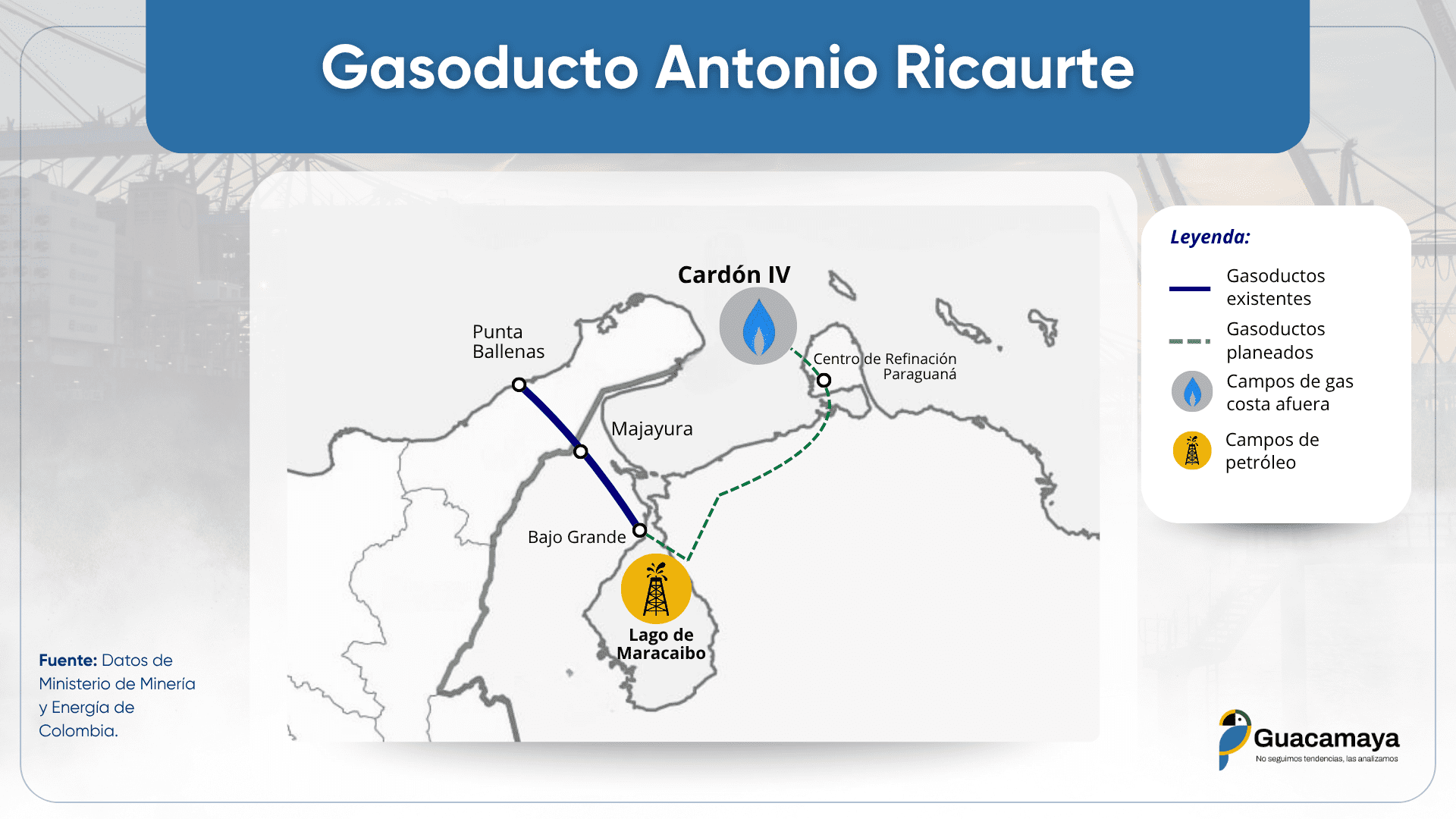

Many find it hard to think that Venezuela’s neighbours will need its gas. Colombia, and especially Trinidad and Tobago, are important producers. During the government of President Hugo Chávez, the Antonio Ricaurte gas pipeline was even used to supply Zulia with Colombian energy. But the two countries overestimated their reserves, which is leading them to frantically search for alternatives.

Globally, gas demand is expected to continue to increase, by as much as 32% by 2050. In Latin America, it has been estimated that gas demand could rise by 83% from 2023 to 2035, from 150 billion cubic meters to 275.

Emerging economies continue to grow, while advances in technology further drive energy requirements, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI). In turn, several countries are trying to reduce the use of oil and coal, as they gradually move to adopt the energy transition.

In this context, Venezuela is key. With 221 trillion cubic feet, it has 78% of Latin America and the Caribbean’s gas reserves, according to BP. However, if it does not take advantage of this moment, countries will look for alternative sources, for example, in the case of Colombia, resorting to fracking and coal. For its part, Trinidad and Tobago has signed agreements to develop gas fields with Guyana and ExxonMobil.

Colombia has already been a net importer of gas since 2016; the United States covers 60% of its deficit, while Trinidad and Tobago covers the remaining 40%. Both of these providers present problems. Liquefied natural gas (LNG), especially from North America, is more expensive. Meanwhile, Trinidad and Tobago, although it can help Colombia today, will soon have a deficit of its own. The island nation estimates it has about 10 years of production left, taking into account proven and probable reserves.

Trinidad and Tobago faces an existential dilemma. Gas accounts for 80% of export revenues. And not only has it built a large infrastructure to export its gas, but its national industry takes full advantage of it, such as steel and petrochemicals. A drop in production is a hard blow to the entire economy.

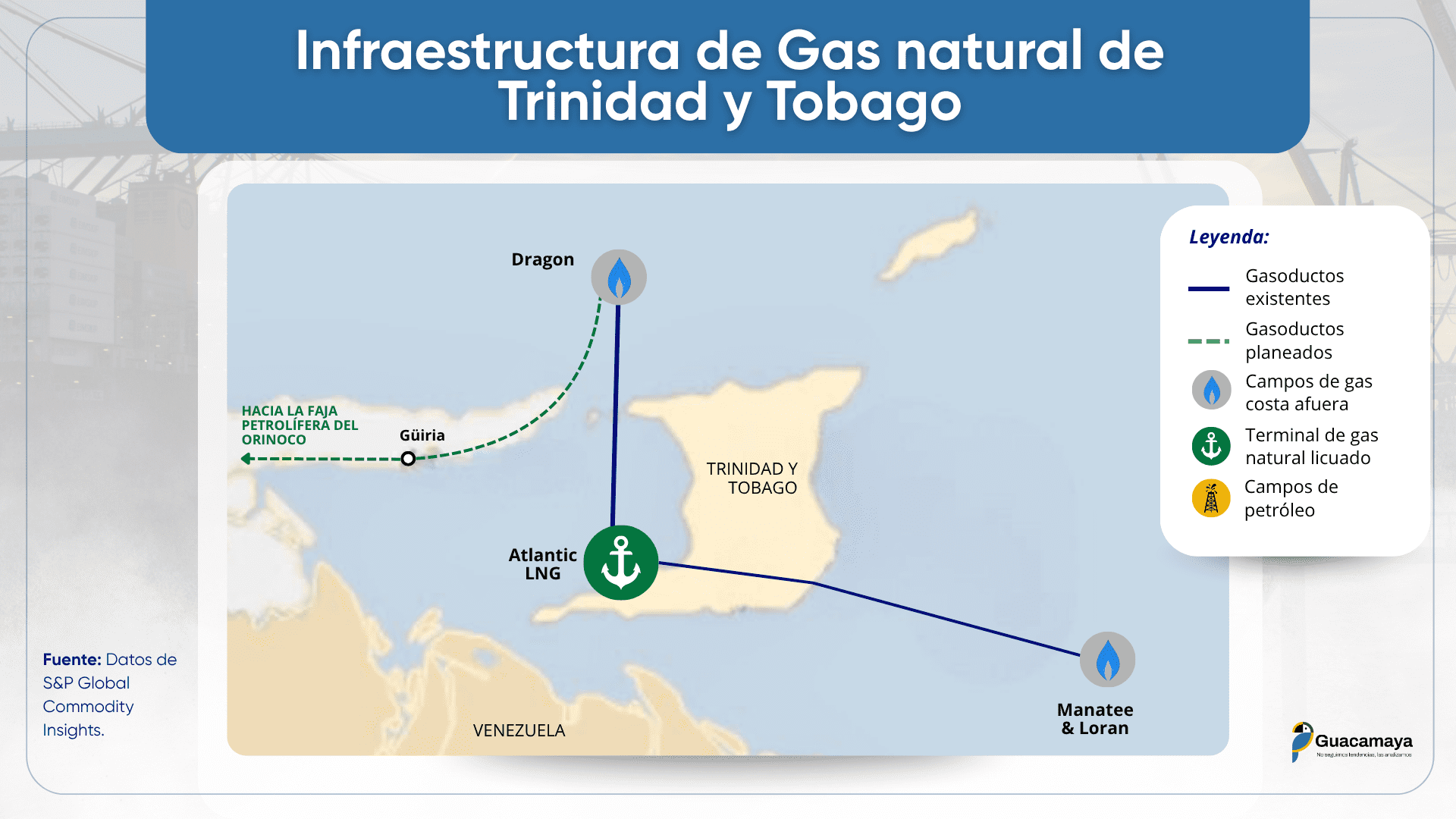

The deficit already exists: with an installed capacity of 4 billion cubic feet per day (BCFd), it only produces 2.6. The island nation has already had to halt operations on a gas liquefaction train, four in total. That is why it is a strategic imperative to access reserves in the exclusive economic zones of their neighbours. Although Venezuela is the closest and with the greatest potential, there is also interest in Guyana, Suriname, and Grenada.

Further proof that both countries need Venezuelan gas is that they have tried to seek special waivers from Washington to access it despite sanctions. Bogota is seeking to activate the Antonio Ricaurte gas pipeline, which connects La Guajira with Zulia, while Port of Spain wants to connect the large gas fields of the Deltana Platform that remain in Venezuelan waters with its own.

We have also seen that the president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, has maintained a cordial relationship with Venezuela, in addition to defending it against US interference, despite the fact that he does not officially recognise Nicolás Maduro as head of state. To a certain extent, although it is not the only factor, it is due to the fact that it maintains its expectation of being able to reactivate the binational gas pipeline.

Even the United States is interested in Venezuelan gas. Colombia and Trinidad, as well as other countries in the region, not only need more energy, but also cheap and reliable sources. Here, pipelines are the answer. Meanwhile, North Americans can sell their LNG in Europe at higher prices.

We are already seeing the first result of the gas crisis: Colombia is returning to coal, and its use is expected to increase in 2026. This marks a very serious setback in the energy transition. On the other hand, if the demand for fuels continues to grow without greater supply, price increases could bring instability and more migration to the North.

Hard connectivity: the lesson of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin

Here is a missed opportunity for Venezuela. It could be tapping into the need of its neighbours to establish trade bridges that result in strategic alliances. The key term is “hard connectivity.”

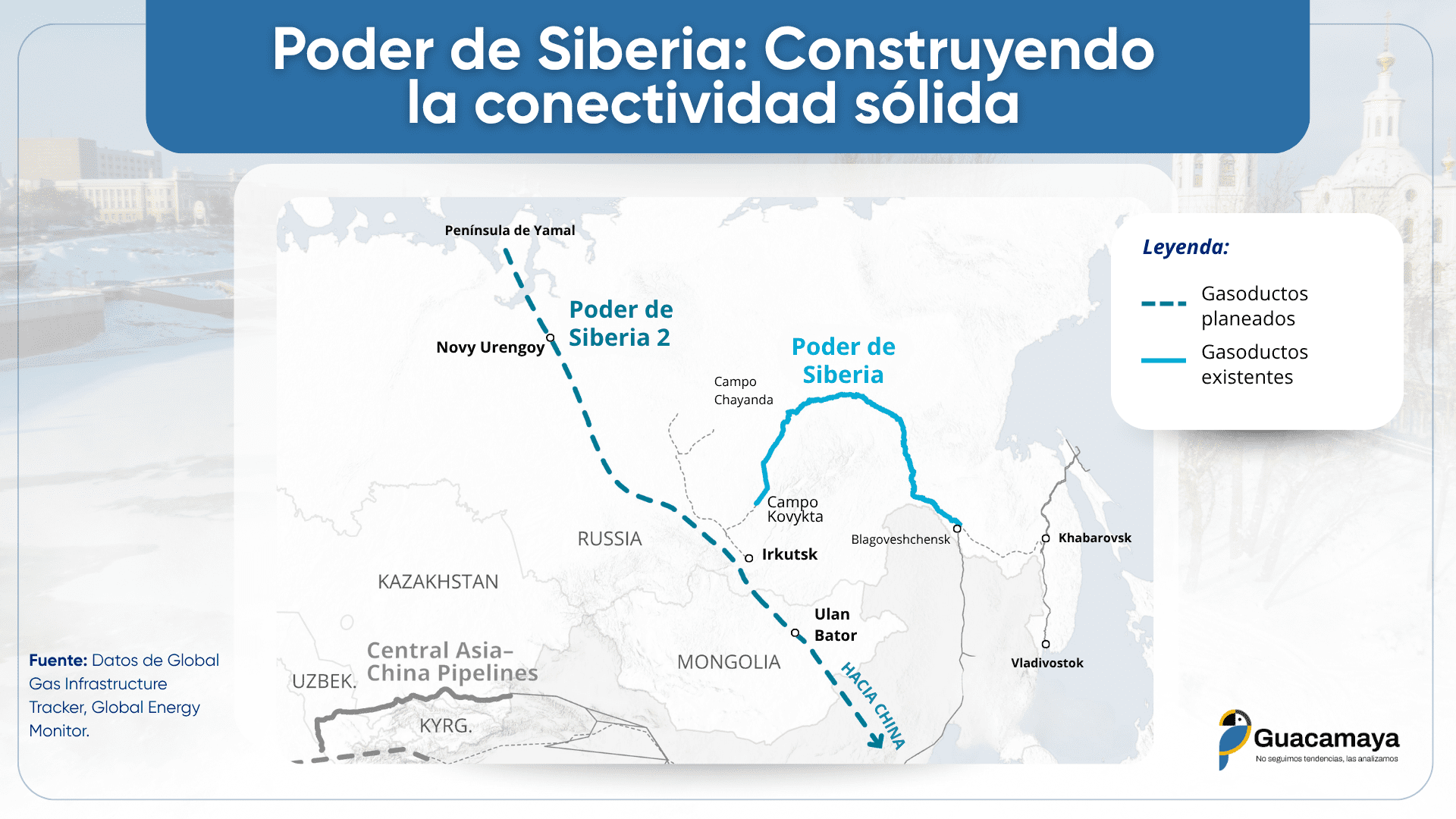

Think about the plans for the “Power of Siberia 2” gas pipeline. It will connect gas fields in the Yamalia-Nenetsia Autonomous District with China via Mongolia. Those deposits, in the northwestern corner of colossal Siberia, are now directed toward Europe.

Why is this pipeline so important? It is a step to break Russia’s hard connectivity with Europe, and replace it with that of China. The pipeline will have the capacity to transport 50 billion cubic meters (BCM) per year, with an estimated life of at least 30 years. Before the war in Ukraine, Europe imported almost 200 BCM per year. With the Power of Siberia 2, China will receive 106 BCM a year through direct pipelines alone.

On the new project, Chinese President Xi Jinping stated that “‘Hard connectivity’ should be a key direction, by actively promoting cross-border infrastructure and energy projects linking the three countries.”

Natural gas has a key difference from oil. The latter offers “soft connectivity”, as it is more efficient to transport it in tankers. These can be directed anywhere in the world. It can also be achieved with liquefaction and cooling of the gas, but this means higher costs. The cheapest, fastest and most efficient way to export it is by pipeline. And this kind of infrastructure forces the countries involved to commit for decades.

In 2022, as Russian troops were approaching Kiev, the decision was made in Brussels to stop buying energy from Moscow. But it is not an easy task, and it is being implemented very slowly. In 2021, 40% of pipelined gas came from Russia. After many efforts to reduce it, in 2024 11 % still came courtesy of Gazprom. Sanctions have to wait. The reason: the cost of U.S. LNG is twice as high as Russian pipeline power, not to mention that several countries in Central and Eastern Europe do not have the necessary infrastructure.

Today, Venezuela will have great natural wealth, but it remains irrelevant at the international level if it does not change its vision. The other countries are not interested in gas that they cannot buy, nor do they consider oil that can be obtained in any other market to be strategic. The United States can afford to sanction Venezuela, just as Europe, Latin America and India agree to abide by this unilateral imposition. When they depend on a stable, cheap and efficient supply of energy, another rooster crows.

The solution: A gas market to promote regional integration

Gas represents a great opportunity for Venezuela. But today it is not being given the importance it deserves. Decision-makers see it solely as an internal problem: producing cheap or free gas. The wholesale price is regulated at the lowest level in the region, at an average of $1.4 per million BTU, while being offered at no cost to the general population – including the wealthiest families. In addition, there is a problem with collection with both public and private entities, completely undermining the profitability of the sector.

There is a clear lack of vision. Gas could serve as a tool for regional integration, to strengthen ties with Latin America and the Caribbean. In the soft connectivity of oil, Venezuela is irrelevant. Their neighbors, no matter how much oil they need, can buy it anywhere in the world with great ease. Whereas, with the hard connectivity of gas pipelines, Venezuela can build stone bridges, which will resist through the decades.

The result of the current policy is simple: without companies being able to cover their expenses and make a profit, they will not invest in gas. Now, if PDVSA intended to invest in its production, this problem would not exist. The State could assume the losses.

But this is not the case; It is no secret that all the investment of the public corporation goes towards oil. It is more profitable, and Venezuela urgently needs the foreign currency. In addition, due to unilateral U.S. sanctions, the Venezuelan government does not have the capacity to raise capital in international financial markets or multilateral institutions.

But then, why are private companies not allowed to invest in gas? They can provide the capital and take the risk. The legal framework already allows it: we are talking about the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons of September 1999, enacted under the presidency of Hugo Chávez and which is still in force.

There are already private companies producing gas without the participation of the State, as allowed by law and the Constitution. Today, total production is 1.7 trillion cubic feet per day. Of these, 1 is a derivative of oil extraction by PDVSA and its partners in the joint ventures. The remaining 0.7 is free gas, in fields such as Cardón IV, where Eni and Repsol have a 50-50 partnership. In the vicinity of Trinidad, Caracas has also approved licenses for projects where energy giants BP and Shell would collaborate with the island’s National Gas Company. In this case, we are talking about the Dragon, Manatee and Loran offshore fields. Unlike oil, PDVSA does not need to participate as a partner; Companies must only pay their taxes and royalties in accordance with the law.

Increasing gas production in Venezuela is much faster and easier than in other countries, if you start by capturing the associated gas. Let us remember that the country produces and consumes 1.7 BCFd. But it actually extracts 4 BCFd from the subsoil. Unfortunately, all that surplus is flared and vented. In other words, it is wasted into the atmosphere, with all the negative consequences on the environment, and without any economic advantage. The most frustrating thing is that with just a fraction of it, the domestic demand of Colombia and Trinidad and Tobago could be covered.

The key step is for consumers who generate a profit from gas, whether public or private, to pay for it. The new scheme is yet to be defined: the government could continue to subsidize prices for families with lower incomes, for example. But today, zero or advantageous costs are being offered to both middle- and upper-class families, as well as to public companies and the largest private ones.

The commercialisation of gas also requires investments for its operation, such as installing meters and pipes, marketing, and creating a network of customers and collectors, for example. Again, the State can let the private sector put up the capital and do this work.

The advantages are many, apart from the fact that a surplus of gas could be generated for export in international markets, reporting foreign currency to producers and the treasury. The incentive to invest could result in the installation of direct gas in all urban areas, replacing cylinders. This would reduce costs while offering a higher quality of life for the population.

Replacing liquefied petroleum gas and diesel with direct natural gas would also give a boost to the national industry, which largely relies on power from power plants. Let’s think about the agricultural industry in Acarigua, Portuguesa. While diesel costs between $15 and $20 per million BTU, direct gas could be delivered at $7 per million BTUs.

The regional integration brought about by the pipelines does not depend on whether the gas is produced by PDVSA or a private company. The important thing is to generate hard connectivity between countries, a bond capable of strengthening the union between neighbouring nations for decades. The State will always be the greatest beneficiary.