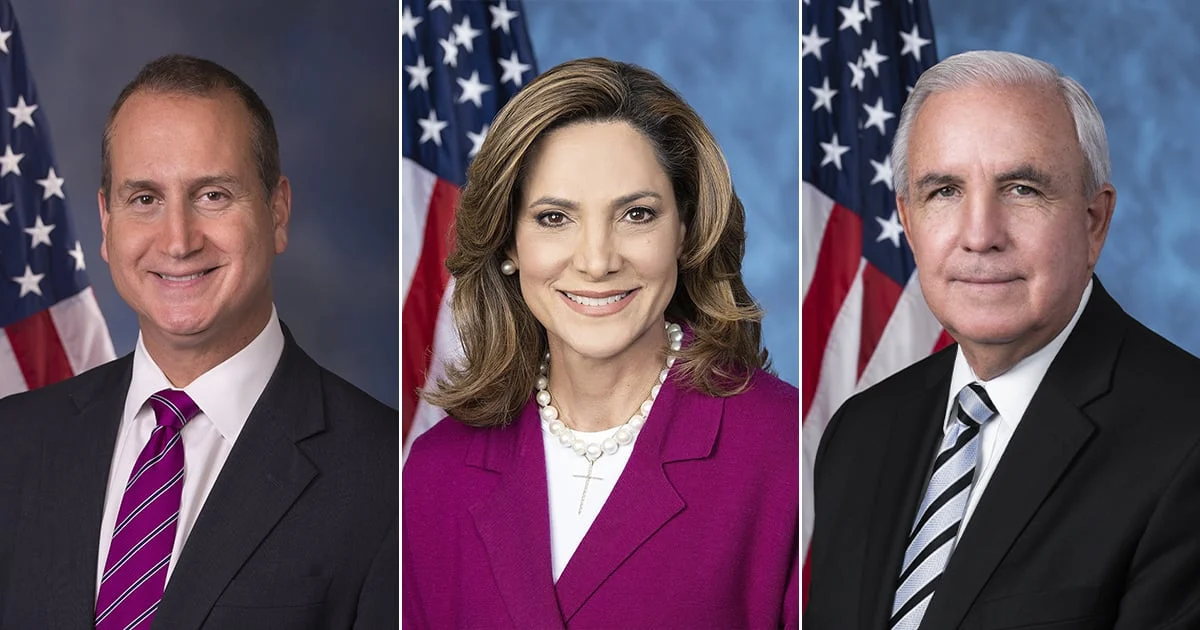

From left to right: Representatives Mario Díaz-Balart, María Elvira Salazar, and Carlos Giménez. The three Cuban-American Republicans represent districts in South Florida.

Three congressmen reportedly pressured U.S. President Donald Trump to end the “Chevron License,” according to an exclusive report by Axios.

They are representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives, all three Republicans from districts in South Florida. They also share Cuban roots: Mario Díaz-Balart, María Elvira Salazar, and Carlos Giménez.

Axios explains that the representatives threatened Trump to revoke General License 41, which allows Chevron to produce and export oil in Venezuela despite sanctions. The Republican Party holds a narrow majority in the House, so just these three could block bills by voting alongside Democrats.

The “Reconciliation Act,” a reform to the current federal budget, passed by two votes, with 217 in favor and 215 against. In fact, Republican Thomas Massie opposed it, joining the Democratic caucus.

“They’re crazy, and I need their votes,” Trump reportedly said privately when he first signaled he would revoke the license, according to journalist Marc Caputo at Axios. Eight hours after the vote, the president announced his decision on Truth Social.

The announcement surprised many observers because Trump had simultaneously agreed to resume repatriation flights with the Venezuelan government. Joe Biden’s attempt to revive negotiations with Nicolás Maduro also failed.

However, the Trump administration has gone further by seeking to revoke Temporary Protected Status (TPS), arguing that conditions in Venezuela are favorable enough to accept deported migrants.

Of the 17 countries on the TPS list, only Venezuela is being targeted for removal. Around 600,000 Venezuelans could see their U.S. residency affected if the status expires this year, risking deportation.

Regarding TPS, Salazar and other Florida representatives have proposed extending protections to the Venezuelan community in the U.S. However, their priority appears to be sanctions on Venezuela, which they imposed as a condition for supporting the budget.

Who are they?

House Speaker Mike Johnson, a Republican, has referred to them as “crazy Cubans,” adding, “as we affectionately call them.”

Carlos Giménez is the only one born in Cuba, in 1954, arriving in Miami with his family in 1960, a year before Fidel Castro came to power. María Elvira Salazar was born in Miami’s “Little Havana” in 1961, the same year as Mario Díaz-Balart, though he was born in Fort Lauderdale.

Interestingly, although none of the three lived under Castro’s rule, they have built their political careers around opposing the Revolution. Today, they are the latest generation of Cuban-American politicians staunchly defending the embargo on the island, in place since 1960, arguing it is the only way to bring down the communist regime.

They are joined by Secretary of State Marco Rubio and his special envoy for Latin America, Mauricio Claver-Carone. Although most now belong to the Republican Party, they have also had the support of former Democratic Senator Robert Menéndez, who represented New Jersey from 2006 until 2024, when he was convicted of corruption and bribery.

Despite the long-standing embargo on Cuba failing to yield results, Cuban-American politicians have decided to extend the same strategy to Cuba’s closest ally: Venezuela. First, they supported Trump’s efforts during his first term to isolate the country and help Juan Guaidó seize power. Failing that, they have backed bills to codify economic and financial sanctions against Venezuela.

The embargo on Cuba has endured for over six decades largely because it includes laws passed by Congress, such as the Helms-Burton Act. Meanwhile, sanctions on Venezuela mostly depend on executive orders from the president, making them more flexible.

Salazar has proposed the REVOCAR Act, which would prohibit all transactions with Venezuela’s energy sector until a regime change occurs. If passed, it would eliminate the White House’s ability to issue licenses for oil companies like Chevron, Repsol, or Schlumberger.

In September, Salazar and Giménez introduced the VALOR Act, which would reaffirm financial sanctions on Venezuela’s Central Bank, PDVSA, and state debt issuance. It would keep Maduro’s government out of the International Monetary Fund, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Organization of American States. It would also block funds sent to countries aiding the Venezuelan state.

Neither of these two bills has been approved, but they succeeded with the BOLIVAR Act, introduced by Michael Waltz, now Trump’s National Security Advisor. This act would prohibit the U.S. federal government from contracting companies that have done business with the Maduro-led state.